3 November 1816: Benjamin Robert Haydon: His Life & his Eventual Suicide

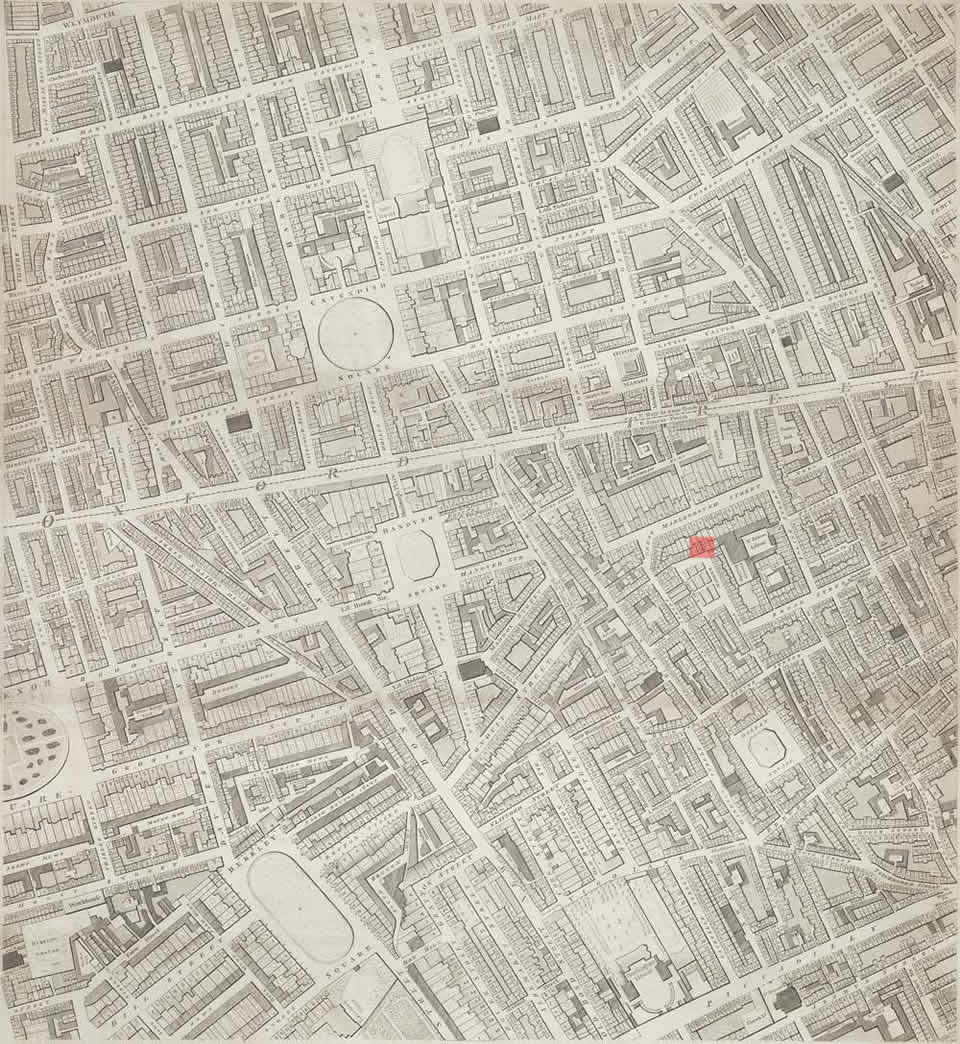

41 Great Marlborough Street, London

Keats visits the studio on 3 November 1816—he comes for breakfast. Keats has met Haydon earlier at Leigh Hunt’s cottage in Hampstead. Haydon decides that Keats will be included as a face in his massive, crowded painting Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (which no doubt thrilled the unknown, striving young poet). Haydon makes a sketch of Keats for the painting in November 1816, and he also makes the iconic life-mask of Keats mid-December.

Early in their relationship, Keats is more or less dazzled by Haydon, and not just because of his reputation and his strong

theories about art: Haydon is acquainted with numerous famous persons of the era,

including

William Wordsworth, whom Keats will meet in

late 1817 via Haydon. Keats is more than thrilled that Haydon plans to send Wordsworth

some of

Keats’s poetry (though Haydon delays sending it for about a month)—Keats writes to

Haydon that

the idea of Wordsworth seeing his poetry puts him out of breath

(21 Nov). But the

relationship between Haydon and Keats is hardly one-way: Haydon quickly returns enthusiasm

to

Keats in affectionate ways that in fact exceed Keats’s regard for him.

To speculate a little: Part of Haydon’s complex and precarious personality is wrapped

up in

his pushy belief in his own genius and destined greatness. When he meets Keats, he

is

probably, first, attracted to Keats’s gracious and engaging character; second, Haydon,

like

others, would have recognized Keats’s very obvious intelligence and dedication to

pursuits

linked to higher beauty and art; and third, Haydon felt that Keats himself was destined

for

greatness, and attaching himself to the young poet might have elevated or at least

confirmed

his own ambitions, as well as offering an association with the young poet, thereby

putting

himself in mentor role. But one thing is sure: Haydon makes Keats truly believe in

his greater

poetic purpose: as Keats now writes to Haydon, I begin to fix my eye upon one horizon

(21 Nov).

Keats writes a fairly innovative sonnet this month that celebrates Haydon’s significance

in

Great Spirits now on

Earth (Wordsworth and Hunt are

praised along with Haydon). Keats sends the sonnet to Haydon in a letter of 20 November.

The

poem also contains a self-reference: it mentions other spirits . . . standing apart / Upon

the forehead of the age to come.

One characteristic is noteworthy in Keats’s sideways

reference to himself: much of Keats’s poetry intimates or points to the future, and

in his

early poetry, the future he often fashions is wrapped up in his desire to become an

enduring

poet, though his ambitions are too often bogged down in somewhat immature notions

of poetic

fame. We might blame youth and ambition; we might also point to Hunt, who is at times

fond of

nurturing notions of celebrity, including (and particularly) his own.

Importantly, Haydon will show Keats the Elgin Marbles in March 1817, which is a minor turning point in the development of Keats’s theories about art and beauty: How do the silent, mysterious sculptures engage the imagination? How do they challenge mortality and exemplify immortality? Haydon also comes to cast doubts about Hunt’s manner and influence, and at least part of his motivation has to do with competition for Keats’s allegiance.

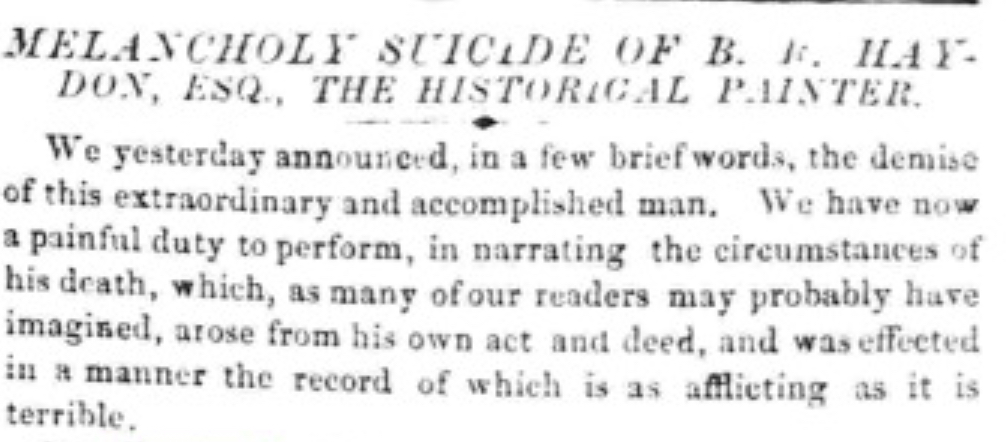

Haydon’s eventual end will not come well, or even easily. On the morning of Monday, 22 June 1846—after a history of compromised eyesight, chronic debt that led to imprisonments, drawn-out and antagonistic relations with the art world, and not receiving the accolades of greatness he insisted he deserved—Haydon commits suicide . . . and a nasty one at that, involving shooting himself once and slashing his throat twice. Yet, in a way, his life reduces to a somewhat banal narrative: the tragic story of disappointed ambition, fueled by early success, much vanity, and then sinking failure. Haydon is sixty-one years old.

Besides those gigantic historical canvases that achieve indifferent merit, Haydon will leave behind his wonderful, detailed, and easefully written autobiographical work. They overflow with vivid description, touching recollections (like the death of his dear old mother), as well as amazing moments that express his utter determination to succeed with his persistent belief that he deserved success. We also have his encyclopedic, doctrinal lectures on art, though at moments these carry some stubborn principles about what he believes constitutes High Art. Both sets of writing reveal Haydon’s passion for and reasoned defence of creative work; they show an extraordinarily intelligent and critical mind, a voracious reader, a masterful writer (it should have been his calling!), someone who knew everyone, and a man who, at moments, and beyond his self-admiration, touchingly prays for help from God to forgive his hypersensitive and volatile nature, and to forgive his failures over earthly temptations. He also constantly thanks God for what he does have. But his underlying theme is his hope to deliver and to be recognized for some kind of grand vision via his painting; he agonizingly prays to be remembered, but not by failure.

The last two entries of Haydon’s June journal:

21st — Slept horribly. Prayed in sorrow, and got up in agitation.

22nd — God forgive me. Amen.

Finis

of

B. R. Haydon.

‘Stretch me no longer on this rough world.’ – Lear.

End of Twenty-sixth Volume.

Besides his diary and memoirs, Haydon left some other papers. He records his last

thoughts

about an hour before he kills himself, including the idea that evil should not

be used even for the sake of good, which might give us pause to consider how Haydon

viewed his

own life. Then, on another paper, he names his executors, praises his wife, and, as

a list, he

enumerates (1-19) various items, including his assets/debts relative to the worth

of his

paintings, a summary of his considerable debts (he’s well into the red); pardon for

those

debts (which, he writes, were the result of his precarious vocation); the names of

numerous

supporters to whom he is grateful; hope for his children; a statement that he has

done his

best in the name of art for his nation with the hope of acknowledgment. And then he

asks God

to forgive his sin of suicide, and he’s certain God will hear his explanation for

all he as

done; he also forgives his enemies, as well as both his worthy and unworthy

creditors.

These are curious, touching, astute, and complex papers—Haydon can be blind and discerning at the same moment. But in the end, we picture a man with a determined vision of significant but unrecognized accomplishment in his head, with grateful love for those close to him in his heart, but with, as they say, a chip on his shoulder—and a large one at that.

[See Keats’s social network, which shows the importance of Haydon.]