1 or 2 March 1817: Keats’s On Seeing the Elgin Marbles

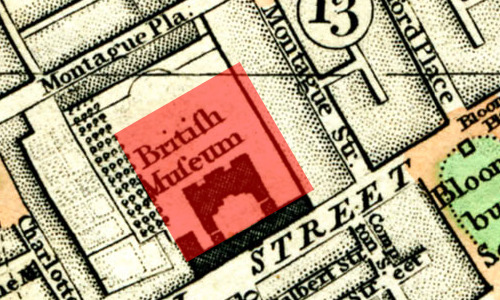

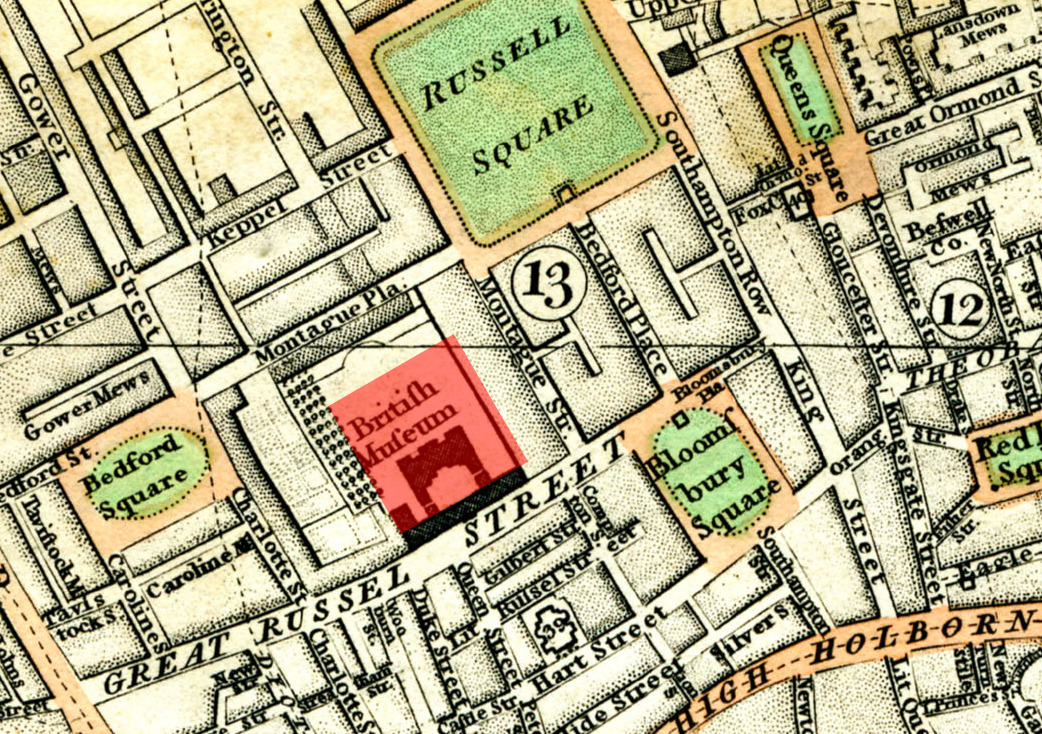

Montagu House, British Museum, London

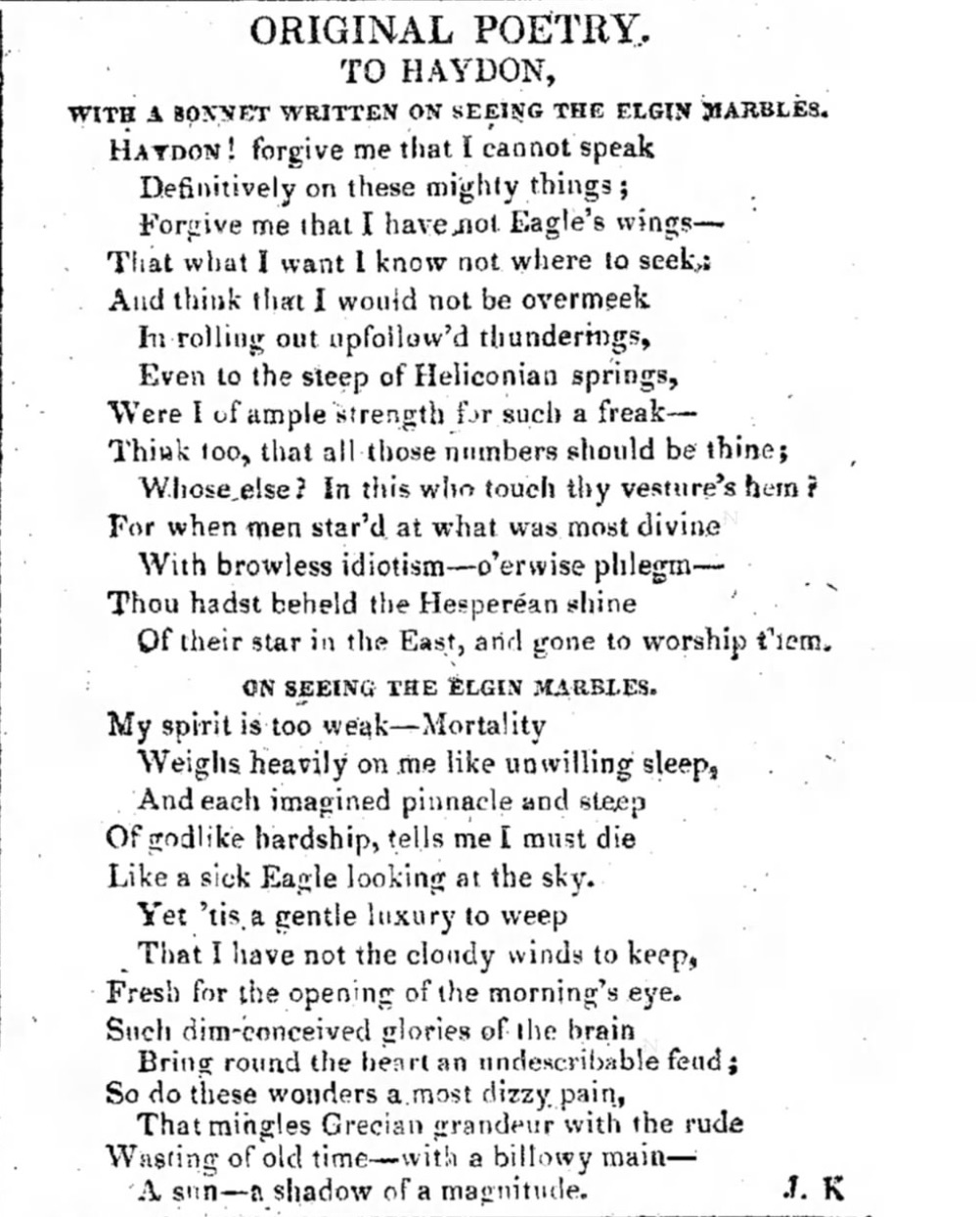

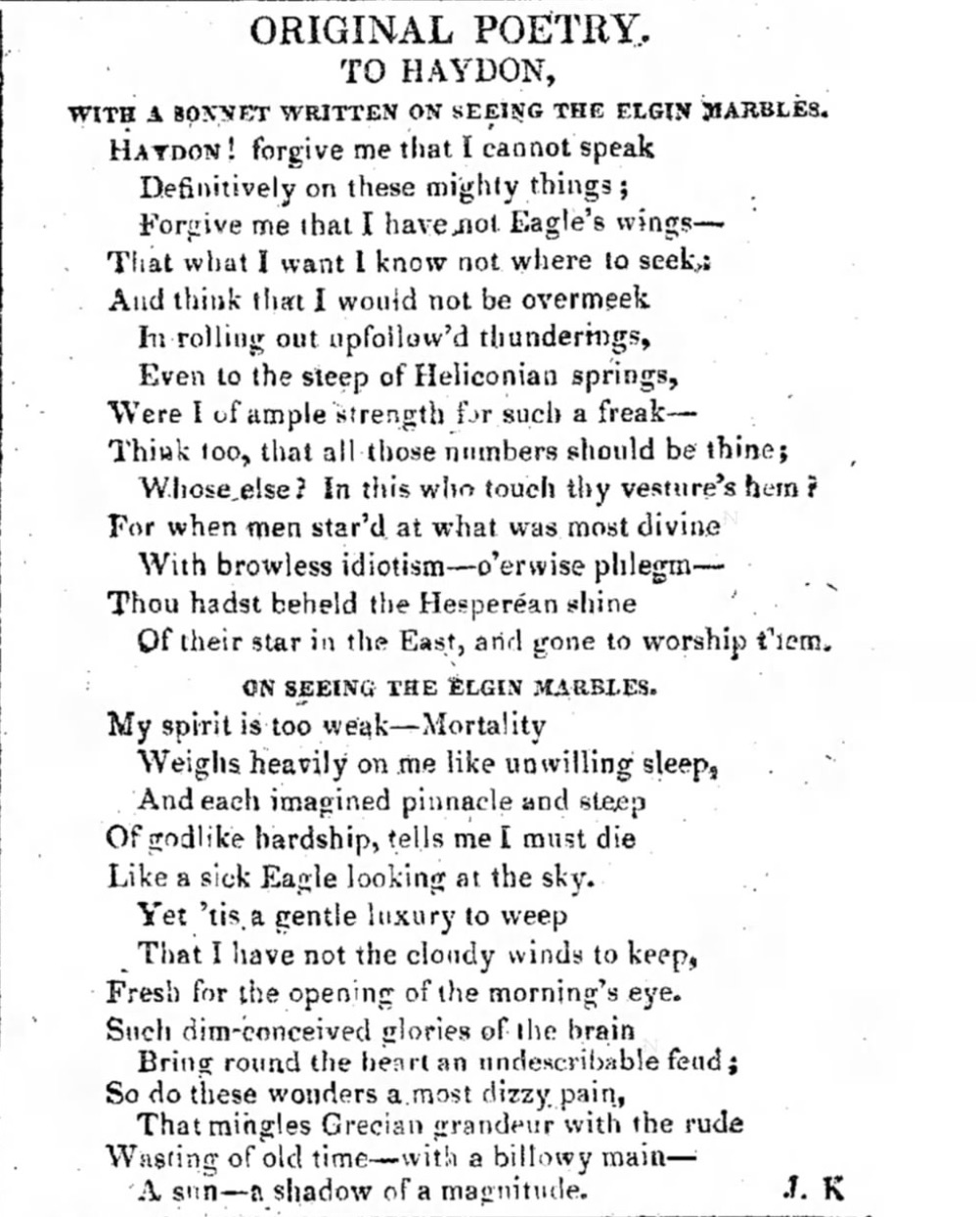

Keats sees the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum with the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon and perhaps with poet and reviewer John Hamilton Reynolds. Two poems are immediately inspired by the exhibition: On Seeing the Elgin Marbles and To B. R. Haydon, with a Sonnet Written on Seeing the Elgin Marbles. Both sonnets are published about a week later in The Examiner and The Champion, and in both cases the publication has to do with Keats’s relatively new connections—with Leigh Hunt (who co-owns, edits, and writes for The Examiner) and Reynolds (who writes for The Champion). Letters written during the month confirm Keats’s close relationship with Reynolds and Haydon; Keats meets both via Hunt. Worth keeping in mind is that part of Haydon’s reputation at the time is based on his strong public defence of the Elgin Marbles. Haydon went to some length to argue that the Marbles are much, much more than crumbling fragments of human forms. Along with others, he wins the argument. Haydon feels, in fact, that the Marbles might even inspire the youth of the nation.

During Keats’s time, there was much debate about the Elgin Marbles—which, between 1801 and 1805, were taken from Greece by Lord Elgin, who was the ambassador to the Ottoman Empire at the time. In 1816, the British Parliament legalized the action and placed the Marbles in the British Museum after purchasing them for 35,000 pounds, and they have been on display there since 1817, though moved to a more prominent place. The naturalistic yet classical beauty of the sculptures, their material worth, their providence, and the natural (rather than overly idealized) figures only further adds to their controversial significance. That the marbles were, in a way, stolen or looted objects from Greece, haunts discussion of the Marbles; to this day, the British Museum strongly argues that the 1816 agreement is binding and appropriate, and that the BM is the right and rightful place for showing and preserving the Marbles; they are exhibited in what today is called the Parthenon Gallery.

Seeing the Elgin Marbles is hugely inspirational for Keats—poetically, philosophically, and personally. And no doubt, during Keats’s visit, Haydon is the lens through which Keats, at least initially, sees the marbles. Keats will return more than once to look upon the Marbles and the unknowable—but imaginatively potent—story they tell.

The complex qualities of art (sculpture and painting, in particular, but music, too) increasingly become an implicit subject and motif in Keats’s work. Keats begins to respond to art’s beckoning but uncertain silence, and what it can capture, express, and inspire even with (and perhaps because of) its mystery. The truth of beauty in art, and how it leads to thoughts about timelessness and mortality, moves Keats’s poetry in certain important directions, culminating in his extraordinary Ode on a Grecian Urn (written spring 1819).

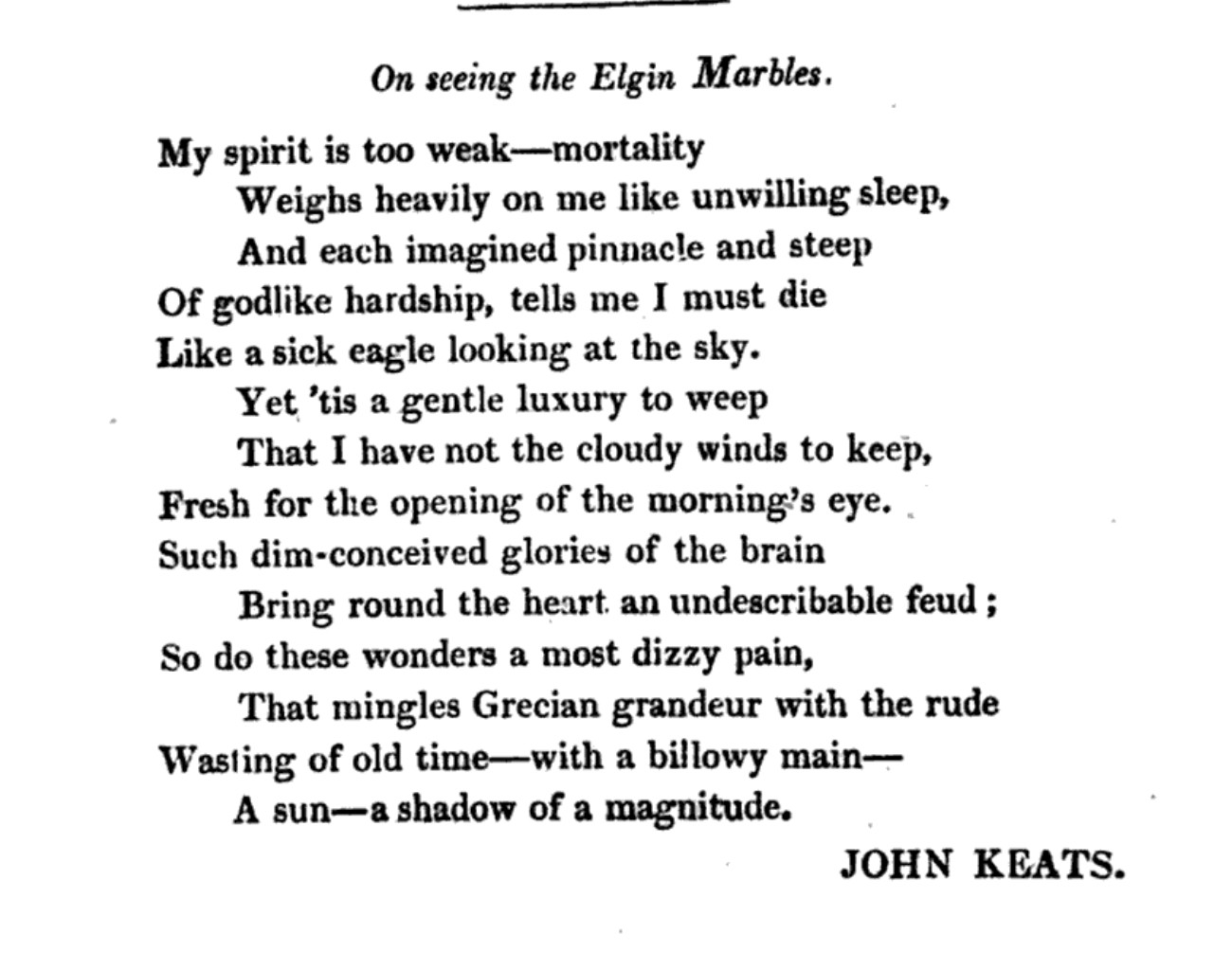

But this early (and particularly in the On Seeing . . . sonnet) we detect that Keats is capable of developing phrasing and emotional distance that frees his voice to express both passion and elegance, closeness and distance, and with some equally early signs of originality. This takes place when Keats moves between his own complex and conflicted response to the inspirational objects—the individual in time facing art’s timelessness. Much of the phrasing in the sonnet comes to us easily, yet (to borrow from the sonnet), at the same time, it weighs heavily upon us; it mingles what we are with what we cannot conceive. Keats’s voice feels at once personal and universal, and this does not happen much in his early work, but almost always in his best work (mainly that of 1819).

The powerful anonymity of the marbles is not lost in Keats’s developing poetics—and

then in

his poetry. The present but invisible hand of the artist becomes or is absorbed into,

as it

were, the form it imagines, then creates, and then shapes: this is what Keats will

strive for

and achieve in later poetry. For now, at least, we have poetry not cluttered by flimsy

sentiment, flowery phrasing, or arbitrary purpose, despite the existence of a few

cloudy and

cluttered phrases in the sonnet to Haydon, like browless idiotism, o’wise phlegm.

And

so a rising Keatsian subtext surfaces in the two occasional sonnets—namely, the voiced

picturing of a striving and overwhelmed poet confronting the silent, enduring, and

mysterious

beauty of art. How can he overcome this unsecure striving? Can he—should he—even hope to

reproduce the truth of such power in his own art? How can his poetry represent these

qualities of profound uncertainty? In terms of Keats’s progress, the crucial

intermingling of these subjects will developmentally move him toward his best poetry,

that of,

mainly, 1819.

Keats sends the two Elgin sonnets to Haydon, who praises and is quite naturally moved and flattered by the second of the sonnets (To Haydon . . .).

During March, Haydon and Keats trade a few letters, and clearly they feel like kindred

souls

in their quest for artistic immortality. Haydon this month tells Keats that you add fire,

when I am exhausted, & excite fury afresh—I offer my heart & intellect &

experience.

Keats must have been quite flattered and excited by such unbridled praise

and affection by the older and much more established Haydon. (For a little more on

Haydon, go

to 25 March 1820.)

This is an exciting time for Keats: his first volume of poetry, Poems, is just about to be published (probably on 7 or 10 March) and reviewed by Reynolds on 9 March in The Champion; upon publication, Keats will send copies to the collection to almost everyone he knows; he is obviously very proud—at least for the moment. At least, in a way, he can put his youthful poetry behind him.

Keats’s writing continues, though still too often within the confines of Huntian influence, as Keats and Hunt playfully, though also a little embarrassingly, crown themselves with laurels (see the poems On Receiving a Laurel Crown from Leigh Hunt and To the Ladies Who Saw Me Crown’d). But there is competition for Keats’s sympathies and in guiding Keats forward, mainly from Haydon and less from Reynolds. Keats feels he needs to find a way to devote more of his energies to writing, and doing so without distraction. He is also attempting to develop a sense of originality, which he will first articulate in his poetics before fully achieving it in his poetry.