14 June 1819: Strapped for Cash, Averse to Writing, Ability Summoned, & No Longer a Versifying Pet-Lamb

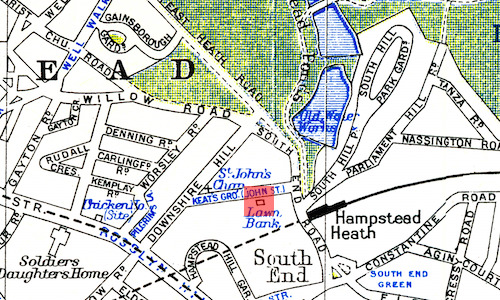

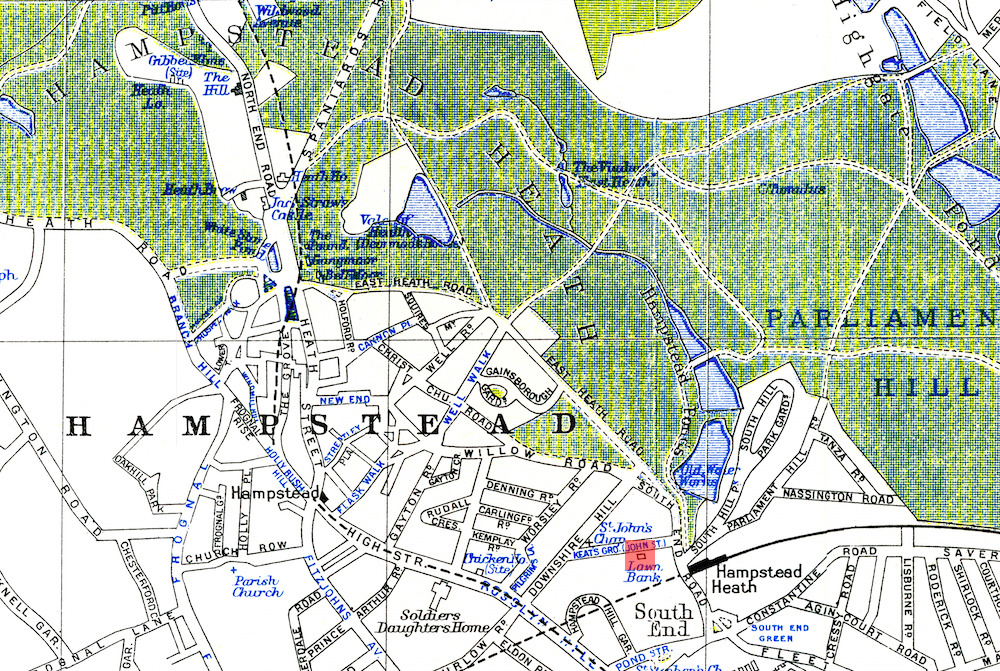

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

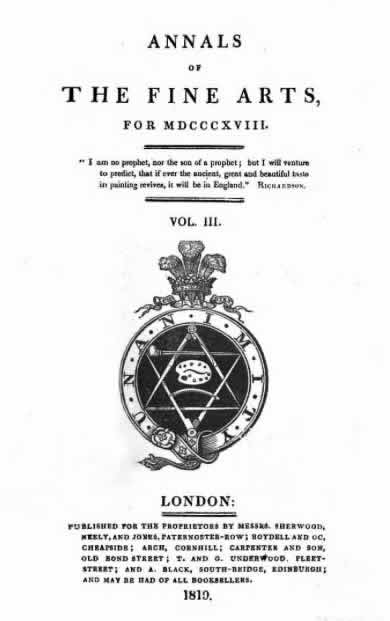

From Wentworth Place, Keats, aged twenty-three, sends a copy of Ode to a Nightingale to James Elmes,* editor of Annals of the Fine Arts. It is published in the July issue. The poem articulates Keats’s desire for a pure, free, and natural poetic voice that can escape from or transcend the human world of sorrow, suffering, uncertain consciousness, and dark mortality: What is Art’s place in the larger, creative context of pain and joy, life and death, the actual and the ideal. [For extended commentary, see 12 May 1819.]

The middle of June finds Keats desperately scrambling for money, mainly idle and unsettled,

suffering from the return of a chronic sore throat, but still vaguely hopeful that

he can,

with increasing discipline and experience, produce something of note, even if just

to make

some money. He expresses to Sarah Jeffery in a letter (9 June) that fame no longer

motivates

him; at the same time, he feels a certain kind of maturity as a poet, and he put into

perspective what he once was: I hope I am a little more of a philosopher than I was,

consequently a little less of a versifying pet-lamb.

But at the moment he is very

averse to writing,

even if he hopes with all my industry and ability

to try

the press once more,

which likely refers to writing and selling a play with his good

friend, Charles Brown (17 June). By the end of

June, Keats is on the Isle of Wight, at Shanklin, hoping to save some money, avoid

the London

crowd, and work on what he hopes to be the cash-generating play with Brown, Otho the Great. Because of

cold weather, the trip to the island reactivates that lingering throat condition.

Elmes is a good friend and supporter of one of Keats’s close friends, Benjamin Robert Haydon, the historical painter. Haydon and Elmes had been students at the Royal Academy. No doubt the connection came through Haydon, who at times had a fair amount to do with the journal.

The publication of Ode to a Nightingale likely generates a tiny sum of much-needed money for Keats. At this point, he is basically broke and living on the goodwill of a few friends. He finds out that family money is held up on Chancery because of a possible suit against it, and the credit he has been living on (based on inherited money) has probably just about run out. Just a couple of days after writing to Elmes about publication of the poem, Keats in fact asks Haydon, who is also suffering financially, to repay money Keats had earlier loaned to him. In the end, Haydon’s constant issues with money are far worse than Keats’s—and in the end contributes to to his suicide in 1846.

The journal also publishes Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn (in January 1820), thus making the Annals the first public venue of two of Keats’s greatest works. Earlier, in March 1818, Elmes publishes Keats’s On Seeing the Elgin Marbles and To Haydon with a Sonnet Written on Seeing the Elgin Marbles, though these poems were first published in the same month they were composed, March 1817, in The Examiner and The Champion. Keats initially sees the Elgin Marbles with Haydon on or about 1 March 1817. Haydon’s interest in Keats’s work is always keen, unconditional, and sincere, though now and then a little self-serving.

*Elmes, who is also a surveyor, engineer, and reputable architect, ends up writing a memoir of Haydon. Like Haydon, Elmes feels strongly about rescuing the Elgin Marbles for the sake of posterity and art.