9 June 1819: Abatement of Fame; or, Beg What You Can for Me; & No More Pet-Lambing Verse

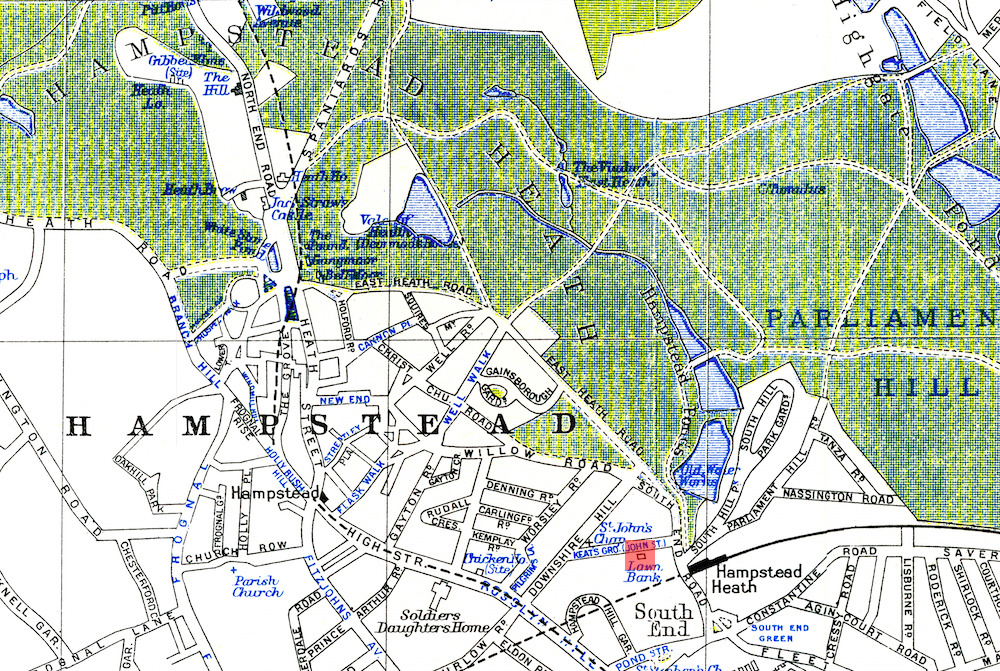

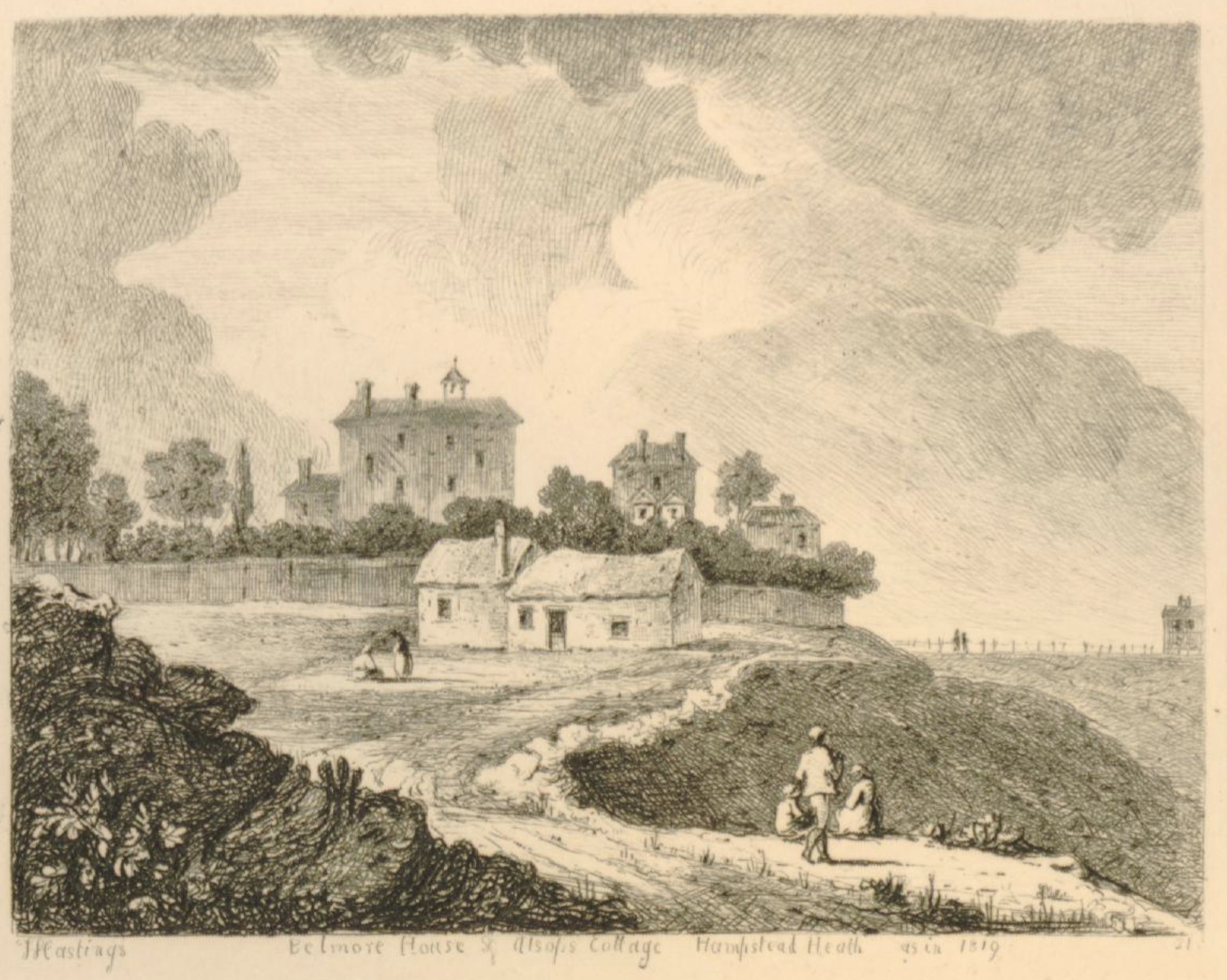

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

In June 1819, Keats, aged twenty-three, finds himself in very serious financial difficulty:

his inherited family money, which he has been getting in unpredictable bits and pieces

from

the variable overseer of the family estate, Richard

Abbey, now seems to be in dispute—or so Abbey suggests (letter 17 June, to Haydon). For a few years now, Keats has been living

almost exclusively on credit based on his capital from this family legacy, but it

appears this

may be dwindling. That Keats needs to make a living forces him to entertain emigrating

to

South America or to become a ship’s surgeon, though he seems to give up on these ideas

by

early June. Keats also attempts to call in all loans that he has himself made. Keats

confesses

to his sister, Fanny, that he does not have enough

money to take a coach to see her (letters, 14 and 17 June); to his friend, the painter

Benjamin Robert Haydon, he writes, Do borrow or

beg some how what you can for me

(17 June). That he continues to experience a chronic

sore throat does not help his circumstances and ability to travel.

So after an extraordinarily poetically productive spring on which much of Keats’s

reputation

will come to rest (though Keats is oddly quiet about what he has done, or unaware

of what he

has just achieved), in early June Keats portrays himself as idle

and very adverse to

writing

because of the overpowering idea of our dead poets and from abatement of my

love of fame.

Giving that just a few years ago Keats used to fawn over the idea of

poetic fame in both his letters and his verse, this is a significant measure of his

poetic

growth. He believes his discipline is to come, and plenty of it too.

At the same time,

and once more putting his maturation into perspective, he also believes he is now

more of a

Philosopher than I was, consequently a little less of a versifying Pet-lamb

(letters,

9 June, to Sarah Jeffery). Importantly, this self-assessment of his progress clearly

points a

sense of depth and poetic maturity, especially relative to much of his earlier ineffectual

poetry—and his immature seduction by Huntian notions of fame: no more crowning each

other with

laurels. Writing his Ode on

Indolence is the thing I have most enjoyed this year,

though the comment

perhaps humorously plays off his reference to being idle.

(When Keats writes the ode is

uncertain, but it might have been written mid or late March, or even into June; it

is by no

means the best of his 1819 odes.)

But all of his plans, no matter how unsettled a state of mind

he has, come to the same

intentions: I cannot resolve to give up my favorite studies,

he writes to his sister,

Fanny, and so I propose to retire into the

Country and set my Mind a work once more

(letters, 9 June). In fact, Keats’s friend

James Rice, Jr., has asked Keats to spend a month

with him on the Isle of Wight, and although Rice is quite ill, Keats has few options.

Again,

in some ways, these comments and his intentions reflect a maturing of his values and

a

refocusing of his poetic ambitions, and given the accomplishment of the spring odes,

these

goals might be both higher yet also realistic. At the same time, there is desperation:

he very

much needs to find a way to make a living, and at the back of his thoughts lurks his

desire to

write a grand poem. Momentum for the long Hyperion poem has now

fizzled, though late into 1818 it kept him practicing his poetry and lifting his poetic

register to approximate Milton’s tone and style.

But something halts him; perhaps it is a sense that he in fact is not a Miltonic poet

whose

artistry is overly artful, for him at least; perhaps it is the poem’s somewhat cloudy

plot and

undetermined thematics that gives him pause.

Keats is now tired: of London; of borrowing from friends, and they from him; of making

the

social rounds; of his chronic sore throat often preventing physical activity; of begging

from

and dealing with Abbey. He is also perhaps tired

of waiting for success as poet, though clearly he remains quietly driven by his belief

in his

powers as a poet. To his sister, he repeats the idea that he can live more cheaply in the

country

(to Fanny Keats, 17 June). Indeed, by mid-June, Keats gets a small loan from his

closest friend, Charles Brown, who persuades Keats

not to return to a medical career but to try the press once more,

which Keats says he

will do with all my industry and ability.

His close friends remain convinced that Keats

should continue to write. For his part, Keats is unsettled.

But at least plans afoot to move to the Isle of Wight are now acted upon in late June, which Keats hopes will result in cheap accommodation. After going through a fierce storm while on the coach ride to Portsmouth (which soaks him, and cannot have done his uncertain health any good), 28 June 1819 finds Keats on the island in Shanklin. He hopes to begin some serious writing, including work on a revenue-generating play—a tragedy—to be written with Brown, who arrives about the third week of July. Keats also has hopes for a long poem, Lamia, which he likewise hopes will have some success; popularity (translation: money) is now more important that enduring fame.

Missing from all of this is what exactly is going on with Keats’s relationship with

: circumstances—uncertain

finances, uncertainty about her personality, uncertainty about his health, his friends’

doubts

about Fanny herself—prevent Keats from pressing forward with or without her. But we

have to

take it that Keats remains emotionally committed to Fanny. We have to keep in mind

that some

success with his writing also increases his chances for being with Fanny; as he writes

to

Haydon, he will make one more attempt in the press

—and he asks Haydon to borrow or

beg some how what you can for me

(17 June). Writing to his sister on 14 June, in the

context of not being able to afford taking a coach to see her, I do not happen just a

present to be flush of silver.

The pressure is on.