30 April 1819: From Unproductive Funk to Fame Debunked

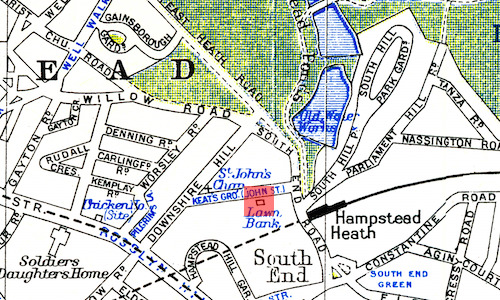

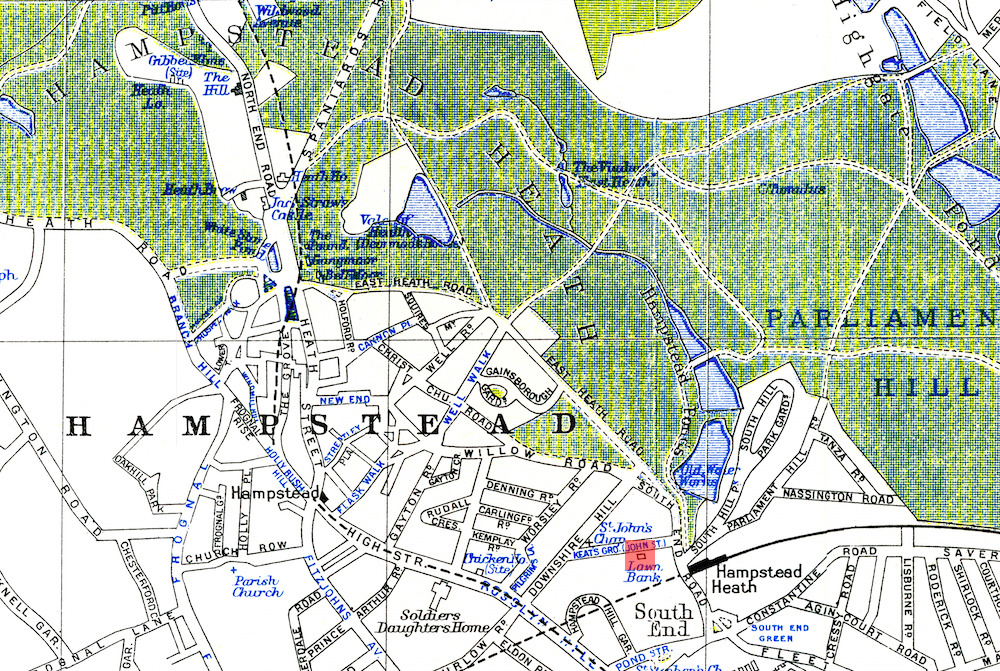

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

April: the month begins in a poetic funk; Keats ends it remarkably.

In a long and absorbing journal-letter to his brother George and his sister-in-law Georgiana

in the US, written over a dozen occasions between 9 February and 3 May, Keats’s initial

and

lingering unproductive temper will now be met with a flurry of significant poetry.

The letter

begins with a sore throat and vague hopes for a productive spring (14 Feb); works

itself

through states of indolence (19 March) and doubts about a poetic future (15 April);

only to

end with complex philosophical thoughts about suffering and Soul-making

—and finally in

poetry itself: La

Belle Dame sans Merci (21 April), a song of four fairies (21 April), four

sonnets (30 April/3 May), and one ode.

The deeply allusive though minimalist La Belle Dame sans Merci perhaps jump-starts Keats’s stymied progress, especially when read as an allegory of the Keatsian poetic position. (See 21 April.)

As noted, in the section of the letter for 30 April, Keats transcribes yet more poetry,

including two sonnets, On Fame (Fame, like a wayward

girl) and On Fame (How fever’d is the

man) (both are published decades after Keats’s death). Just a year or two before,

in his earliest phase as a poet, and perhaps influenced by his mentor of the time,

the poet

and celebrity journalist Leigh Hunt, Keats is

somewhat obsessed by what might be called faux-fame: he is an innocent but coveting

poet in

search of a subject and pining for accomplishment, and consequently his verse is often

stuck

on his desire to be a poet; this ineffectual poetry often overcompensates with Huntian

poetic

affectation. Even as late as March 1818, in his first (unpublished) preface to his

pioneer

and mainly ineffectual poem Endymion, he

declares that one of the reasons he writes is for a love of fame.

Now, significantly, in these two sonnets written about a year later, he posits that

fame does

not follow those who strive too much for it, and neither is it found by those who

too

feverishly seek it. Instead, it will come unsought if left, as it were (in Keats’s

metaphor),

to ripen on its own without any self-indulgence; the key is a stance of poetic composure—a

heart at ease

and with temperate blood.

This idea may, in fact, be filtered

through William Wordsworth’s idea about how

poetry has its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility

(from Wordsworth’s

Preface to Lyrical Ballads, 1800). In fact, Keats exhibits this

new-found calmness in his first of the five so-called great odes,

which he copies into

this letter for 30 April (though the dating could be a few days either side): Ode to Psyche. Keats

writes:

[Ode to Psyche is] the only one [of the poems in the letter] with which I have taken even moderate pains—I have for the most part dashed off my lines in a hurry—This I have done leisurely—I think it reads the more richly for it and will I hope encourage me to write other things in even a more peaceable and healthy spirit.

Indeed, it does. That more peaceable and healthy spirit

may be the creative condition

for Keats very shortly writing masterful odes; what immediately comes to mind is the

rich,

settled tone of Keats’s To

Autumn.

Ode to Psyche

nonetheless remains perhaps the most obscure and least successful or engaging of Keats’s

so-called great odes of 1819. Its form and structure are certainly more slack. Also,

the poem

is, as it were, perhaps too much into-itself, which, however, does mirror or allegorize

the

Psyche myth: self-inflicted Cupid (love) falls too much in love with love. The poem’s

poet

will, at any rate, rescue the under-appreciated Psyche (soul as beauty); and, as Psyche’s

choir

or priest,

he will find a place for her/it in his poetic imagination.

But through his new, controlled rhetorical powers (based especially on repeated words

rather

than weak and wandering synonyms) the poem does partially align itself with the other

odes, as

do the tensions of, for example, stillness and desire, experience and vision, the

material and

immaterial. Keats does, then, manage to hold a topic, turn it, and enter it.

This is what Keats’s earlier work does not often do: the early poetry often skims

along or

rambles about, in search of a topic, a voice, a tension, a vision—and in the case

of the 4,050

lines of Endymion, written mainly in about seven months in

1817, most its lines fill up space for the sake of filling space, with occasional

moments of

uncurbed enthusiasm; there is description for the sake of description; there is imagination

aplenty without it being imaginatively constrained, intense, or purposeful—thankfully,

Keats

is largely aware of this. The poetry in Endymion does, as it

were, play with itself, which conjures what Lord

Byron notes about Keats’s early work: writing to his publisher John Murray, Bryon

characterizes Keats’s poetry as a sort of mental masturbation—he is always f-gg-g [i.e.,

frigging, meaning fucking] his Imagination. I don’t mean he is

indecent, but viciously soliciting his own ideas into a state which is neither

poetry nor anything but a Bedlam vision produced by raw pork and opium

(9 Sept 1820).

Bryon’s dislike of Keats initially rises from Keats’s disparagement of Alexander Pope’s

poetry, and is also tied to class-inflected snubbing that Bryon easily shoved around.

Bryon

strongly disliked what he saw as the pretension behind the vulgarity; after all, as

Bryon

writes in Don Juan, Keats, though promising something great,

without Greek / Contrived to talk about Gods of late

(XI, lx). Yet Bryon is at some

level quite right about Keats’s early work and its self-involved frothiness, as well

as some

of Keats’s early usages that do indeed ring of poetic affectation—or what Byron might

have

called the phoney finery of the shabby-genteel. Interestingly, Keats is aware of the

nature of

the difference between his poetry and that of Bryon on a more refined level, and is

not quite

as condescending toward the older and immensely famous Byron: later in the year Keats

will

write, There is this great difference between us. He [Byron] describes what he sees—I

describe what I imagine—Mine is the harder task

(letters, 20 Sept).

That Keats at this point is now kick-started to progressively pursue poetry is reflected in a sonnet he writes at this time—If by dull rhymes—in which Keats expresses that he is looking for and exploring forms of versification that will be unchained from accepted constraints of both sound and sense. Keats finds such release in the unique stanza forms he develops in his great odes.

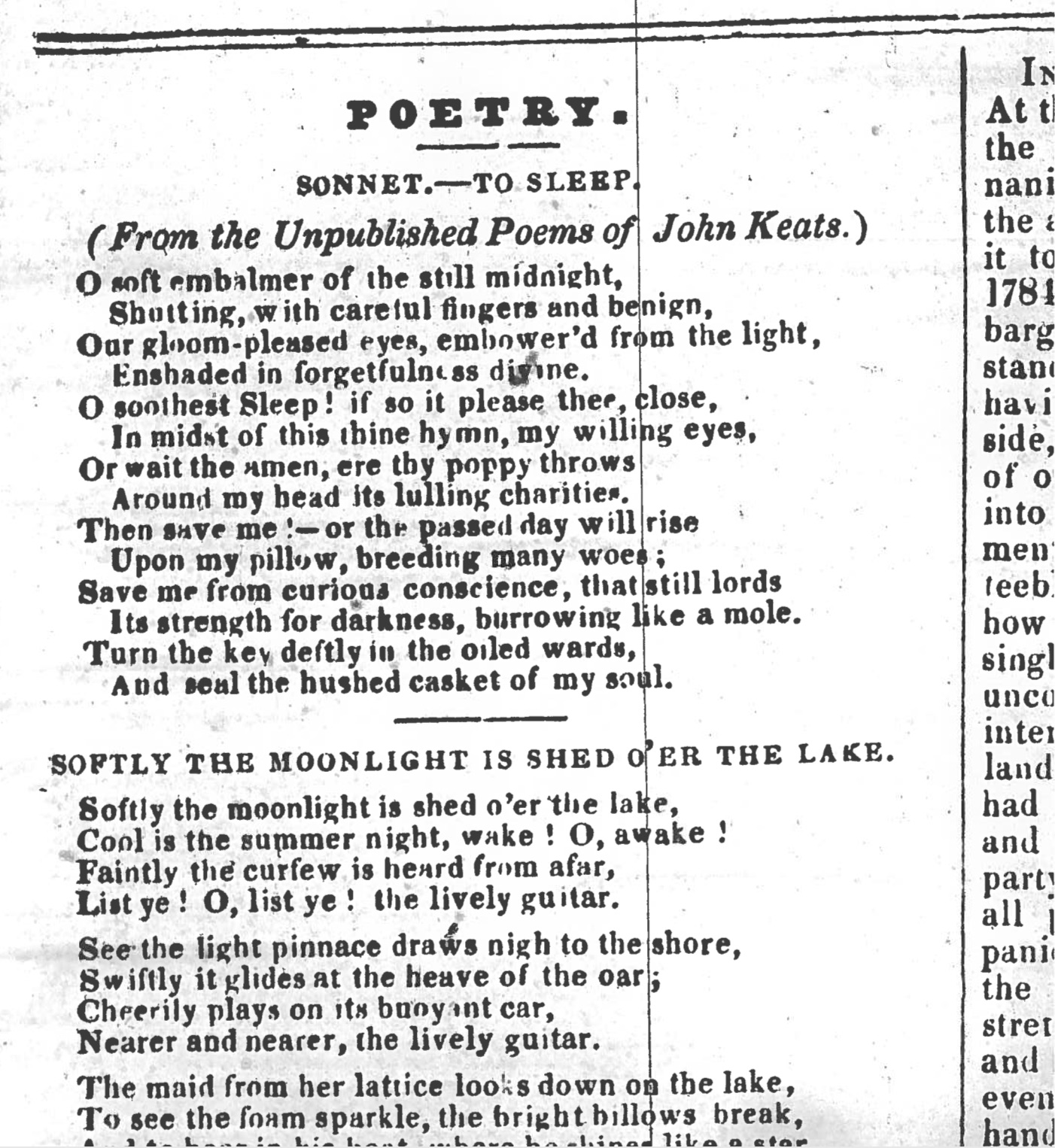

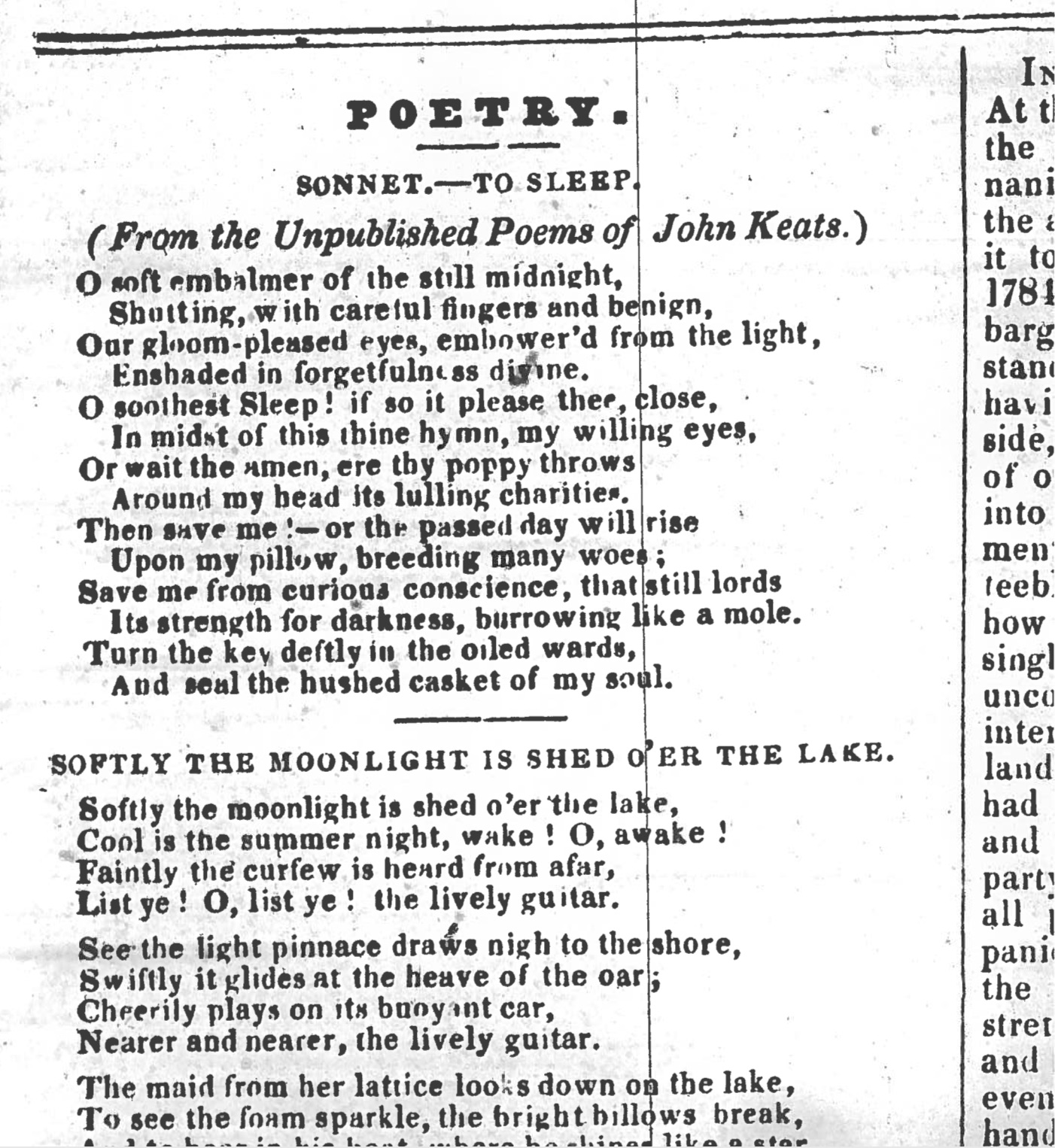

Keats this month also likely writes a decent sonnet—Sonnet to Sleep—in which he hopes that

sleep, and its associative connections with death and forgetting, will save him from

feelings

of gloom and woe, and also from dark, burrowing

thoughts. If anything, the poem

connects with and anticipates his greater poem, Ode to a Nightingale (composed in

May), which also invokes a intoxicated, sinking feeling that conflates darkness with

death; in

the ode, however, he capably makes a profitable leap to imaginatively probe these

feelings and

the state, and, with a more probing voice, he ends the poem with profound uncertainty

that

Hamlet himself might voice.

On the lighter side of things, in The Examiner (for Sunday, 25 April), Keats publishes a lighthearted review of John Hamilton Reynolds’ send-up of William Wordsworth’s poem, Peter Bell (published 22 April). Reynolds calls his poem, Peter Bell, a Lyrical Ballad. If anything, the short review reveals the utter familiarity with Wordsworth’s writing that Keats and Reynolds as close friends share, with closeted respect for and understanding of some of Wordsworth’s earliest poetry, and clear bewilderment over some of his other work. In the review, Keats commends Reynolds’ skillful parody of Wordsworth, while Reynolds has some glee impersonating Wordsworth’s self-perceived poetic worth: “It has been my aim and achievement to deduce moral thunder from buttercups, daisies, celandines [. . .] Out of sparrows’ eggs I have hatched great truths [. . .].” This is pretty funny, and the opportunity for some ribbing at Wordsworth’s expense is not lost upon another of their friends and fellow poets, Percy Shelley, who, from Italy, later in the year, writes and sends his own lampoon, Peter Bell the Third; despite pushing his publisher, it remained unpublished during Shelley’s lifetime (Shelley originally sends the poem via Leigh Hunt, with instructions for publication). For these three younger so-called second generation Romantic poets (and for Lord Byron, too), Wordsworth grows as an easy target for lampoon—and yet a figure who necessarily solicited feelings of deep ambivalence. The question of the older poet’s pretensions is, for some, a little cringe-worthy.