11 April 1819: Two Miles & a Thousand Things

: A Walking Talk by Coleridge

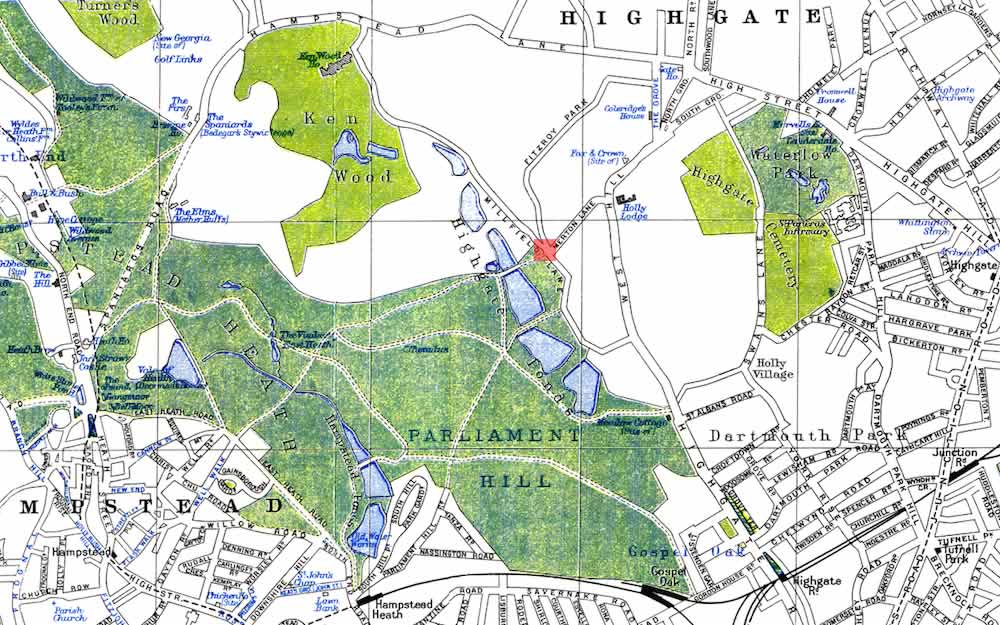

Toward Highgate in a lane by Lord Mansfield’s Park

Where, on a walk toward Highgate in a lane by Lord Mansfield’s Park (Kenwood

or Ken

Wood

), Keats, aged twenty-three, has a chance encounter with the poet, journalist,

lecturer, and literary critic/philosopher Samuel

Taylor Coleridge, who, at age forty-seven, is already a living legend. Coleridge

lives in Highgate at the time (under the kindful watch of Dr. James Gillman), and

is walking

with someone Keats knew from his medical training at Guy’s Hospital, Joseph Henry

Green.

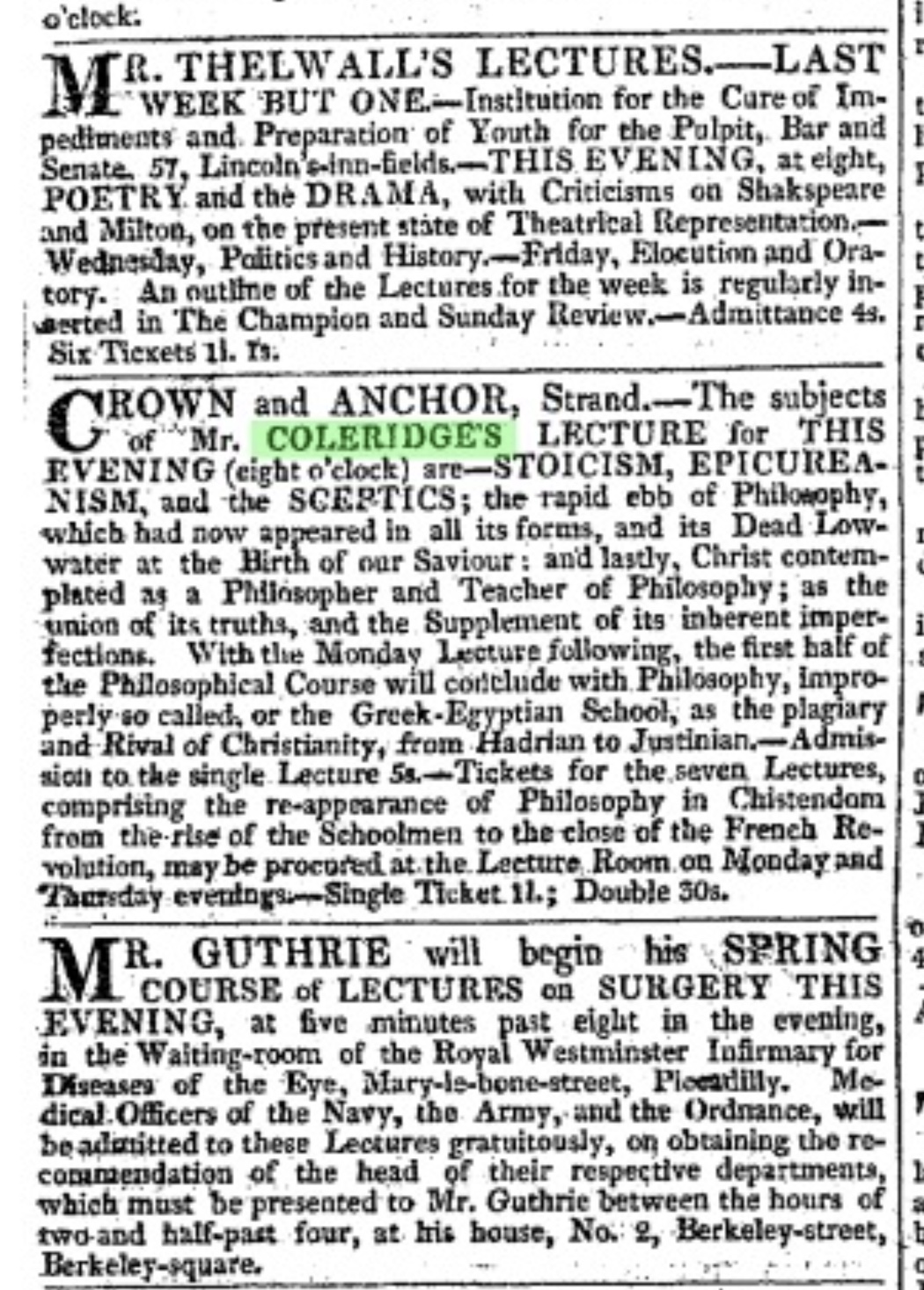

Coleridge (1772-1834) is forever paired with Keats’s most important contemporary poetic influence, William Wordsworth: Coleridge and Wordsworth were, earlier in their writing careers, close friends and co-writers of perhaps the most important single collection of the age, Lyrical Ballads (1798, 1800/1801, 1802), though the volume will, after the first anonymous edition, go under Wordsworth’s name only, with Coleridge’s contribution fizzling; at the same time, Coleridge develops a somewhat neurotic jealousy of Wordsworth’s domestic circumstances, since Coleridge’s at the time are in disrepair. Toward the end of 1818, Coleridge publishes his three-volume edition of The Friend, which collects some of his earlier writing. He also gives numerous lectures over 1818-1819, on both literature and philosophy.* But at this point, in 1819, the poet in Coleridge is all but gone.

Keats’s describes the conversation and gives a brilliant and very humorous account

of Coleridge’s character and sprawling brilliance:

I walked with him at his alderman-after dinner pace for near two miles I suppose.

In

those two miles he broached a thousand things [ . . . ]—Nightingales, Poetry—on Poetical

sensation—Metaphysics—Different genera and species of Dreams—Nightmare—a dream accompanied

[with] a sense of touch—single and double touch—A dream related—First and second

consciousness—the difference explained between will and Volition—so many metaphysicians

from

a want of smoking the second consciousness—Monsters—the Kraken—Mermaids—Southey believes

in

them—Southey’s belief too much diluted—A ghost story—Good morning—I heard his voice

as he

came towards me—I heard his voice as he moved away—I had heard it all the interval—if

it may

be called so

(letters, 15-16 April 1819). This is, arguably, one of the best

descriptions of Coleridge’s complex, ranging character and train of thought.

According to Coleridge’s account of the event

more that 10 years later, Keats returns after they part to press

Coleridge’s hand as a

gesture of reverence to the older poet. Coleridge recalls that he felt death in that

hand,

and when asked how, he recalls detecting some heat and a dampness

in

Keats’s palm. Coleridge here exhibits his gift of enhanced imaginative hindsight.

Coleridge

also remembers the encounter as just a minute or two, though it was probably closer

to thirty

minutes.

Keats is acquainted with much of Coleridge’s

poetry and some of his poetics. Importantly, in formulating his remarkable theory

of

Negative Capability

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817), Keats does so fully in the

context of what he sees as Coleridge’s need to find some sense of truth, fact, reason,

or

certainty, when, instead, Keats posits that the pursuit and expression of beauty

obliterates

uncertainty, doubt, and mystery. An ego-less, empathetic, and open

imagination is what Keats hopes to embody in his best poetry, and with an explorative

voice

that balances disinterestedness with intensity, and with possibilities over certitude;

beauty

provides (or is) its own truth. Keats, however, may not be quite correct in his assessment

of

Coleridge’s poetry, though he may be in assessing Coleridge’s intensely rambling theories

and

poetics (Keats views are likely swayed by William

Hazlitt’s criticisms of Coleridge). In truth, Coleridge’s Kubla Khan may be the most negatively capable poem in the English language, and

certainly some of his best poetry consciously opens up to speculation, irresolution,

and

imaginative leaps; correspondingly, Coleridge’s literary theory of willing suspension of

disbelief

(expressed in 1817 in his Biographia Literaria)

falls in the direction of Keats’s theory, in that it, too, suggests there are truths

in the

impossible via the imagination. [For more about Coleridge’s complex character and

Keats’s

encounter with Coleridge, see my Desperately Seeking

Coleridge.]

At this point in mid-April 1819, Keats notes that he has passed many days in rather a low

state of mind

(letters, 16 April), yet he remains busy socially—wining, dining,

visiting, partying, entertaining, going to galleries, talking to beautiful girls,

taking in

the opera. Toward the end of this period, and after an all-nighter playing cards with

some

close friends, he is so exhausted he says he is not worth a sixpence

(letters, 21

April). Keats also struggles to express his own uncertain finances to his very good

friend,

the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, who is very

upset that Keats had given him false hope for receiving some money as a personal loan.

Keats

apologizes, while trying to explain how his inheritance money has been drained and

held back

by the workings of the trustee of the estate, Richard

Abbey (letters, 13 April).

In terms of his own poetic progress, Keats remains stagnated—fermenting might be the

better

image, given what we know is to come—just as he has for the first few months of 1819.

On 15

April he writes, I am still at a stand in versifying—I cannot do it yet with any pleasure—I

mean to look around at my resources and means—and see what I can do without poetry.

This

does not bode well (continuing worry over money clearly does not help), though there

is a

vague hope in one word: yet.

In fact, within a matter of days, Keats will begin to

break out of his poetic funk, with April the gateway to his remarkable progress into

the

spring of 1819. He has, then, not given up on his climbing poetic aspirations, and

this

encounter with Coleridge on 11 April—the turn of his mind, the depth and range of

his ideas,

the figuring and importance of consciousness—may have pushed Keats’s poetic progress.

Thus

Keats continues to study and read great poetry, and on the 16th he reports how pleased

he is

with the fifth canto of Dante’s

Inferno. But this pleasure may be more tied to a wonderful

floating and kissing dream he has, based upon reading Dante.