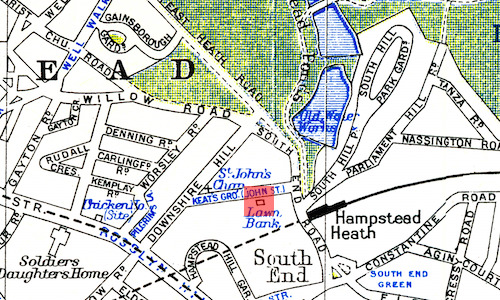

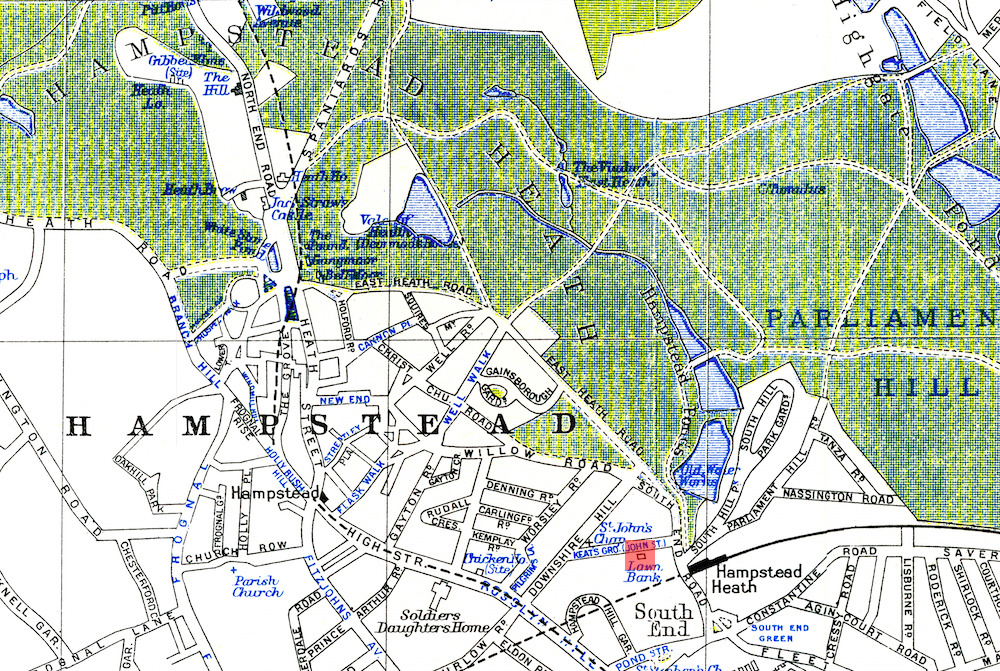

3 April 1819: Fanny Brawne, Complex Associations, & Poetry without Progress

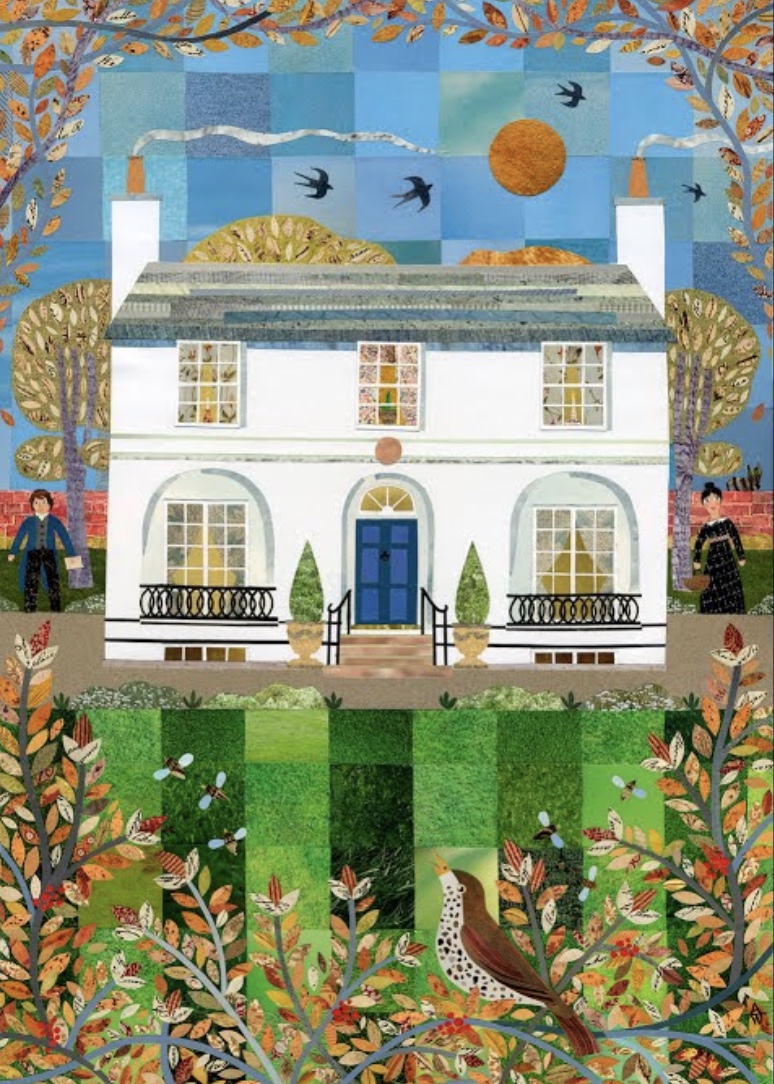

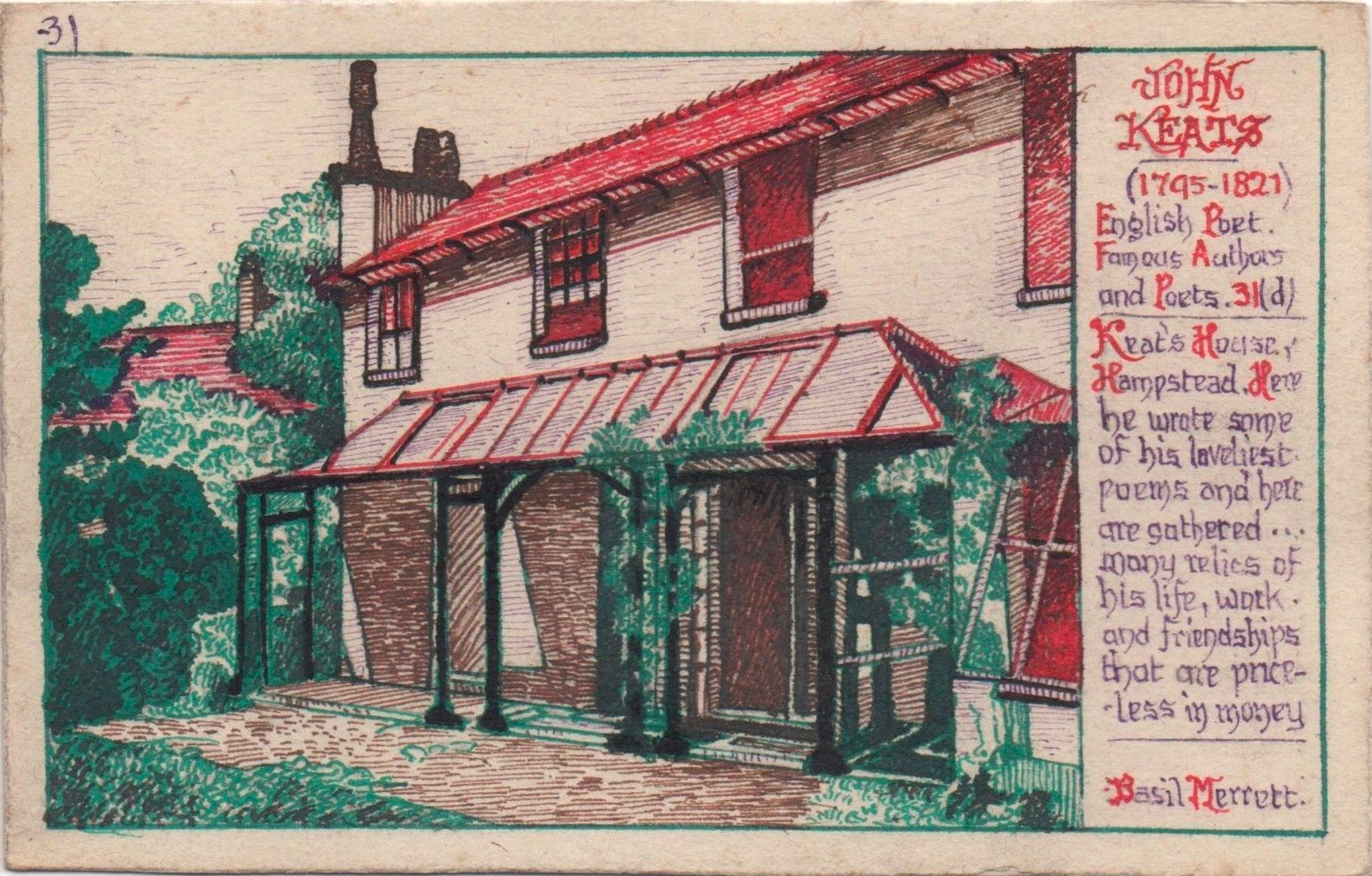

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

On 3 April 1819, Fanny Brawne (along with her widowed mother and younger brother and sister) move into the Charles Wentworth Dilke’s half of Wentworth Place, a relatively new detached double-house in Hampstead. This puts them next door to Keats, who rents part of the other side of the building with his very close friend, Charles Brown and the other owner of Wentworth Place. This, then, puts the two young lovers next door to each other, separated only by a wall, through which they can hear the movements and sounds of each other. We can only imagine ears to the walls.

The Brawne family previously rent this same space in the summer of 1818. They have moved from another location in Hampstead, Elm Cottage. Fanny, about five years younger than Keats, becomes betrothed to Keats in October 1819, though they wished to keep it secret.

We do not know exactly when Keats meets Fanny,

but probably not long after he returns from his northern walking tour, mid-August

1818, but

before December 1818, and quite likely via the Dilke family. Keats and Fanny may have

declared

their love or intentions for each other Christmas day 1818, in the form of some kind

of

understanding,

but Keats still has an eye for beautiful women (at least off-handedly)

into spring 1819. Fanny is quick witted, very fashionable, attractive (but not stereotypically

so), social, and loves dances; Keats is at times possessive and jealous; and though

the two

seem to have some tiffs, Keats does not at first mind their differences. It is clear,

too,

that Fanny is sensitive to Keats’s feeling of loss over the death of his younger brother,

Tom, in December 1818, of consumption. Tom’s

death and Keats’s love for Fanny are likely linked by complex associations and feelings

of

loss, attachment, and love: Fanny lost her own father to the illness.

Most of Keats’s close friends do not approve of the relationship between Keats and Fanny. Rather unfairly, she is pegged as shallow and flirtatious, and a relationship with her is not viewed as being in Keats’s best interests. In fact, she seems supportive of Keats’s aspirations. But thinking ahead somewhat, there is the looming issue of finances: How was Keats to support himself, let alone a wife?*

Although Keats possibly composes a decently accomplished poem about this time—Ode on Indolence—he

nonetheless feels uncertain about his fate and worth as a poet. Unlike his greatest

poetry,

Ode on Indolence,

with its vague ruminations about rumination, lacks sharp or

contrastingly engaged determinations, perhaps reflecting not only Keats’s subject

but his

qualitative engagement with it; that is, there is little progress in the poem about

no

progress. That Keats decides not to publish the poem in his to-be 1820 volume might

suggest

his own downcast or at least indifferent assessment of the poem, even if at one point

later in

the year he declares to Sarah Jeffery he greatly enjoyed writing it (9 June); but

this is not

the same as making a strong declaration about its critical worth to other friends,

like Woodhouse, Reynolds, Brown, or Taylor.

Keats, then, struggles to find a way forward with his poetic progress, though he has

plenty

of simmering ideas about life, human nature, art, and imagination as a form of knowledge

that

overlap with subjects that will, shortly, end up in his poetry. At this general point,

Keats

does express some confidence in his ability to control and focus his creative temperament

in

light of an uncertain world; but, once more, putting this into poetry remains the

problem;

mid-April Keats in fact feels his poetry is at a standstill—I cannot do it yet with any

pleasure

(letters, 15 April). This will change very shortly—and remarkably so. Keats

remains primed with his continued belief in the principle of beauty and the power

of the

empathetic, capable imagination.

*And as usual, Keats’s finances are precarious: over 2-3 April, he withdraws significant funds (over 100 pounds, it seems) from his account tied to inheritance money, depleting at least one source of his income. This month Keats is also upset by one his closest friends, Benjamin Robert Haydon, when Haydon expresses how very hurt he is that Keats has not lived up to his promise to acquire some money for him; Keats attempts to explain his own waning finances to Haydon. Haydon’s life will be plagued by extreme financial and personal problems, and anything Keats can do only offers a moment of minor relief for Haydon. In the end, financial and artistic struggles contribute to Haydon’s eventual (and rather gruesome) suicide.