26 June 1818: Sad—sad—sad

: Lord Wordsworth’s Politics & Forms of Permanence

The Lake District: I shall learn poetry here

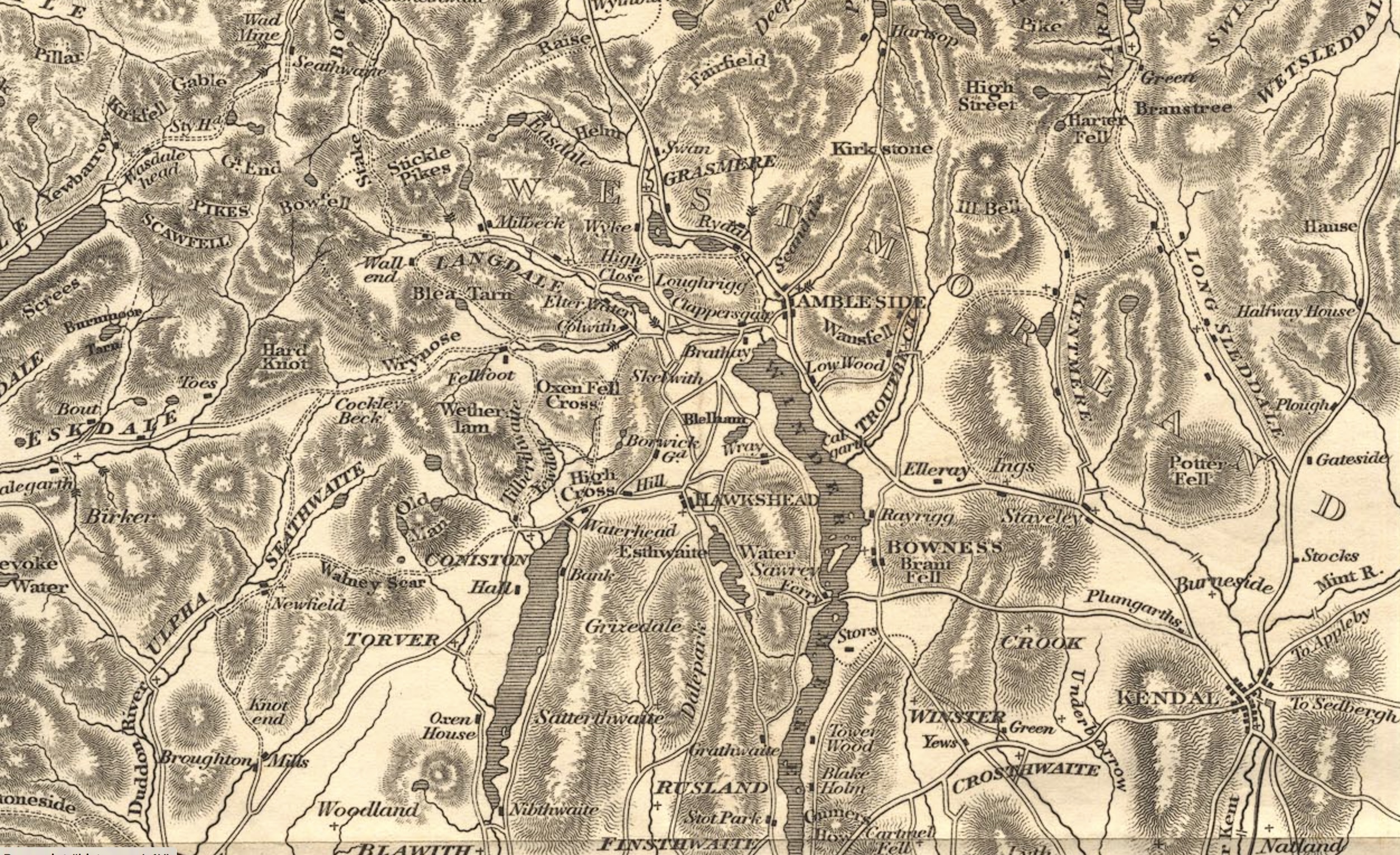

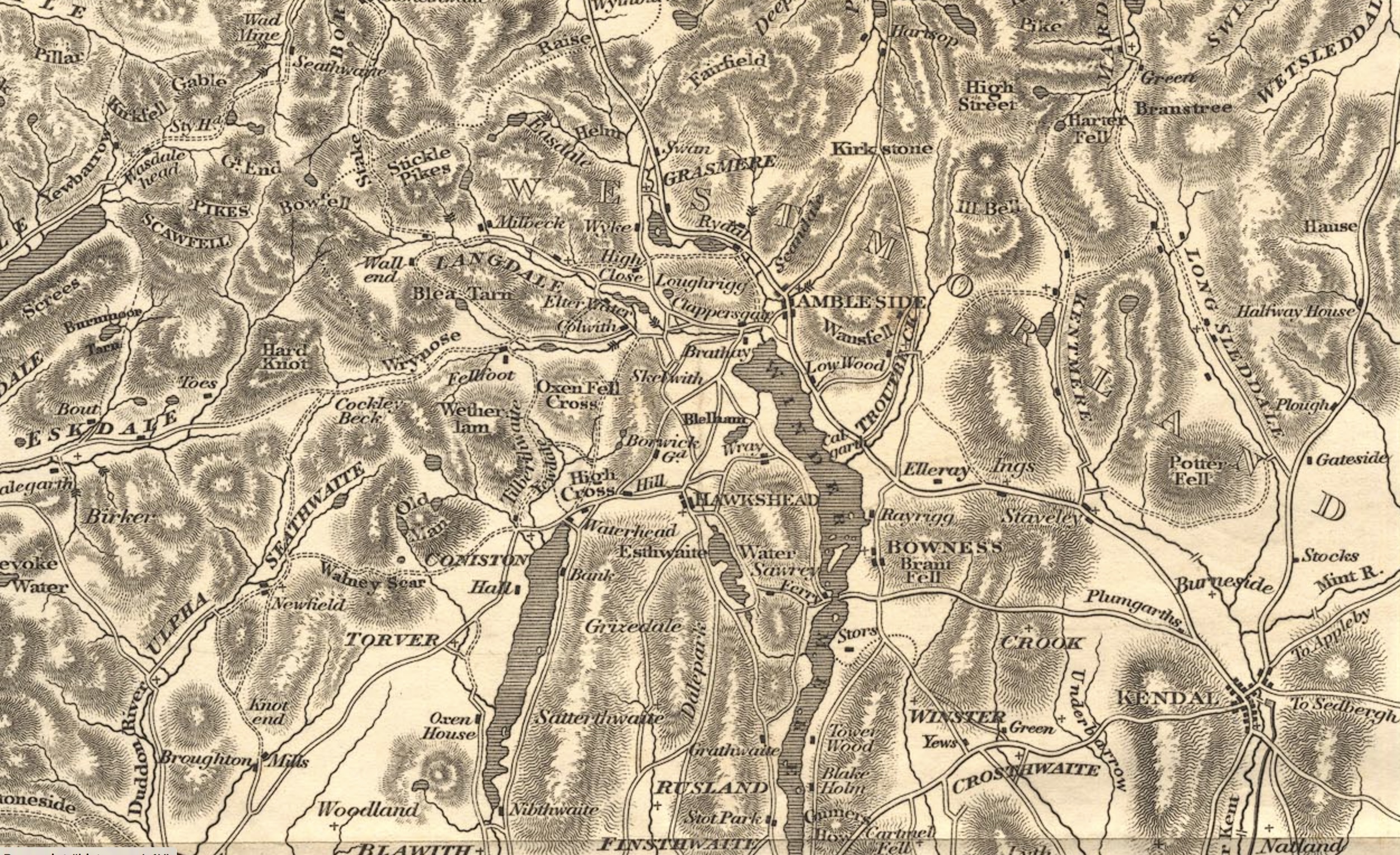

The challenging walking trip north with his friend, Charles Brown, begins 24 June from Lancaster, though heavy rain delays them. The

trip will take them to the Lake District, through (among other places) Kendal, Ambleside,

Rydal, Grasmere, and Keswick, as well as to many sights, like Skiddaw. By the first

week of

July they are in Scotland, before briefly going to northern Ireland, then back to

Scotland.

Keats returns to London by 18 August. They often average about 15-20 miles/day, and

by the

time they are done they’ve walked probably a little more than 600 miles. Along with

beautiful

sights, saddening poverty, and indifferent food, Keats also experiences a few Blisters

(11 July) and increasing fatigue. Bagpipes fall out of favour.

Keats describes what he sees in a purposeful journal-letter to his younger brother, Tom, that he begins 25 June—purposeful inasmuch as he wants to record his experiences in order to later poetically explore them.

The summer of 1818 is long and hot and dry. On 26 June, after having breakfast in

Kendal,

Keats records that he is astonished by the landscape in the area of Winandermere (Windermere)

and the surrounding mountains—in William

Wordsworth’s territory, that is. He sees his first waterfall on the 27th. The

landscape makes him feel that there is no such thing as time and space.

Echoing

Wordsworthian sentiment and language, Keats writes that the combined elements of what

he sees

have a noble tenderness—they can never fade away—they make one forget the divisions of

life; age, youth, poverty and riches; and refine one’s sensual vision into a sort

of north

star, which can never ease to be open lidded and steadfast over the wonders of the

great

Power.

Parts of this recall and reinforce what Keats thought six months earlier as he

attempts to articulate the character of great art: in its intensity [it is] capable of

making all disagreeables evaporate, from their being in close relationship with Beauty

and

Truth

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817). Keats now works to carry over this response to his

poetic progress: he believes that what he can take from the remarkable particular

physical

qualities of this landscape—its space,

magnitude,

and countenance

—will, as a form of permanence, sustain him: I

shall learn poetry here and shall henceforth write more than ever, for the abstract

endeavor

of being able to add a mite to that mass of beauty which is harvested from the materials,

by

the finest spirits, and put into the ethereal existence for the relish of one’s fellows.

[.

. .] I live in the eye; and my imagination, surpassed, is at rest

(27 June). The

landscape, then, dissolves difference and invites participation with something akin

to the

eternal—it has, in short, the qualities of great poetry towards which Keats is working.

Early

in the morning of the 29th, they climb Skiddaw (a little over 3,000 ft.), which has

a summit

that offers remarkable panoramic views.

What makes Keats’s responses important is that he is, in a way, less interested in the landscape per se than in understanding his response to the landscape—the relative and intertwined roles of sensation, imagination, and perception, as well as the subjects that he will attempt to poetically represent, including timelessness intimated by these forms of nature. One problem will be how to translate these powerful elements into human and aesthetic terms, and in particular, to mortality, time, and beauty. In short, these topics will hold a place in his poetic progress in the coming year.

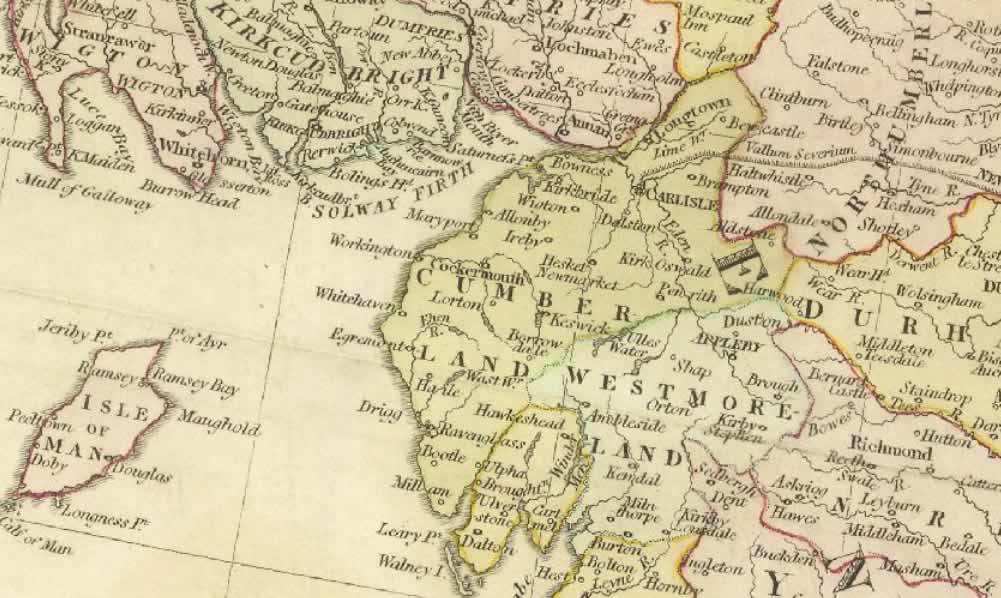

While in the Lake District, Keats asks after Wordsworth. Keats met Wordsworth a number of times in London just over a half year

earlier. (Wordsworth lives at Rydal Mount, Westmorland.) However, Keats discovers

that

Wordsworth is doing some canvassing for [the Tory] Lowthers.

Keats’s reaction:

Sad—sad—sad [. . .].

Nevertheless, Keats had hoped to see Wordsworth. After all,

Wordsworth—good, bad, or ugly—is already a living legend, and knowing him is an extraordinary

circumstance for the young and almost unknown Keats. But Keats’s cynicism is clear:

he calls

him Lord Wordsworth.

Wordsworth’s apostasy was something the Keats circle was very much

aware of, and the Lowther family’s underhanded political control of Westmorland was

utterly

transparent.

That Keats’s close friends—beginning with Leigh Hunt, and continuing with Benjamin Robert Haydon, John Hamilton Reynolds, and Benjamin Bailey—were all well acquainted with Wordsworth’s considerable achievement has steadily encouraged Keats’s study of Wordsworth, which probably begins in earnest in the fall of 1817. Keats’s study of Wordsworth is also motivated by another friend, the critic, essayist, and lecturer William Hazlitt, who parses Wordsworth’s poetic character and greatly shapes (and complicates) Keats’s ideas about Wordsworth’s poetic worth. In discovering and thinking through Wordsworth’s early work, and in particular his expression of joy and sorrow, strength and suffering, loss and recompense, Keats finds significant directions and resources for his own poetic progress, especially as it accelerates into 1819.

Keats wants to explore many of those same regions as Wordsworth, but not in Wordsworth’s style: thus, in Keats’s

important and developing idea of the poetic Character,

Keats offers a crucial critique

of the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime

while favoring the camelion Poet

(letters, 27 Oct 1818). What the poet negotiates does not have to be channeled through

a

speaker’s indulgent subjectivity but through an empathetic, unbiased imagination.

(For an

extended consideration of Keats’s complicated regard for Wordsworth, go to 31 December 1817.)

Now, at this point in June 1818, in Wordsworth’s territory, Keats wants to reconfirm his acquaintance with Wordsworth, again, despite serious doubts about Wordsworth’s political beliefs so antithetical to his own. He manages to leave a note for Wordsworth on his mantelpiece before moving on.

Brown will later record some of Keats’s reactions in an essay entitled Walks in the North (1840). [To view a detailed mapping of Keats’s walking tour, see Keats’s Northern Walking Tour.]

The northern trip does not result in much good poetry, but it does make Keats confront

the

relationship between human character and endeavor on one side, and, on the other,

those

grander, lasting forms of nature—and what is the role or meaning of the imagination

between

the two. The character of Burns, which Keats will

soon have to deal with, also complicates his poetic understanding of fame, misery,

and

accomplishment. Keats returns exhausted and to a very sick brother, Tom—but he also returns with deeper ideas about the direction

of his poetry: as he will write on 21 September, I am obliged to write,

and as noted,

by October his ideas about the poetic character are set. All he needs to do now is

write

poetry that embraces those characteristics—and in 1819 he will.