23 June 1818: Good-bye to George & Looking North

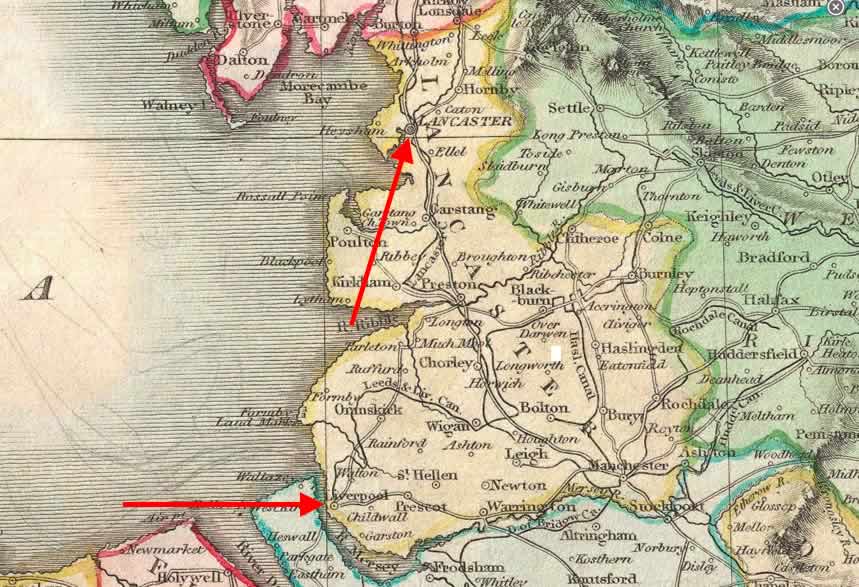

Crown Inn, Liverpool

Where Keats and his loyal friend Charles Brown stay on the first leg of their trip to northern England, Scotland, and (very briefly) northern Ireland. They are saying goodbye to Keats’s brother George, 21, who, with his new wife, Georgiana, will shortly be off to America from Liverpool. George’s goals are relatively simple, though complex and precarious in attaining: employment, property, and relative financial stability—enough so that he might return to England and support his family. George’s first stay ends up in financial loss (Keats feels George has been fleeced by John James Audubon); his second venture in Kentucky (after briefly returning to England to renew finances with some help from Keats), ends up much better. Keats will miss George greatly, but he has great hopes for him. Keats’s letters to George and Georgiana reflect their remarkable trust and closeness. George dies of tuberculosis in 1841, in Louisville, Kentucky.*

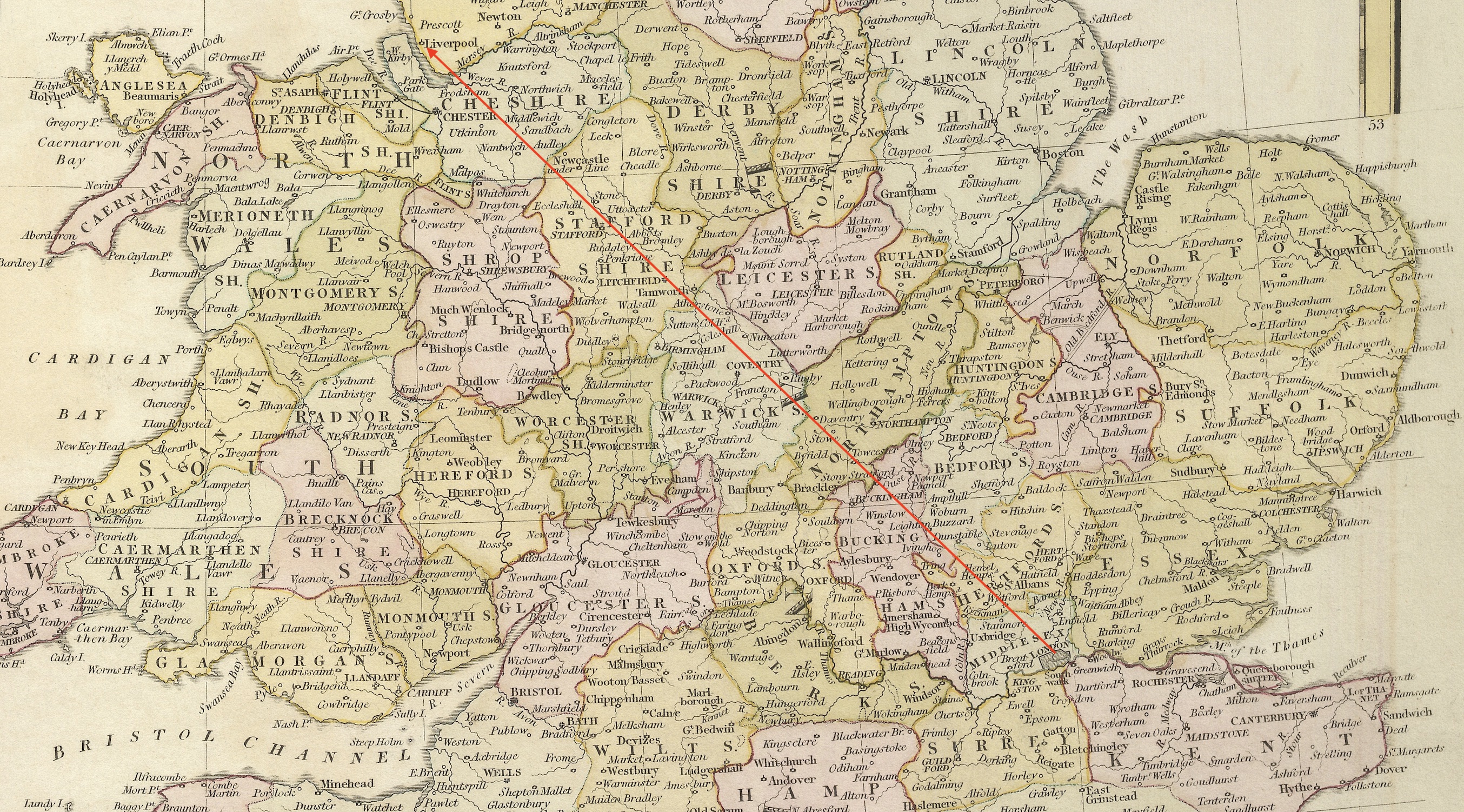

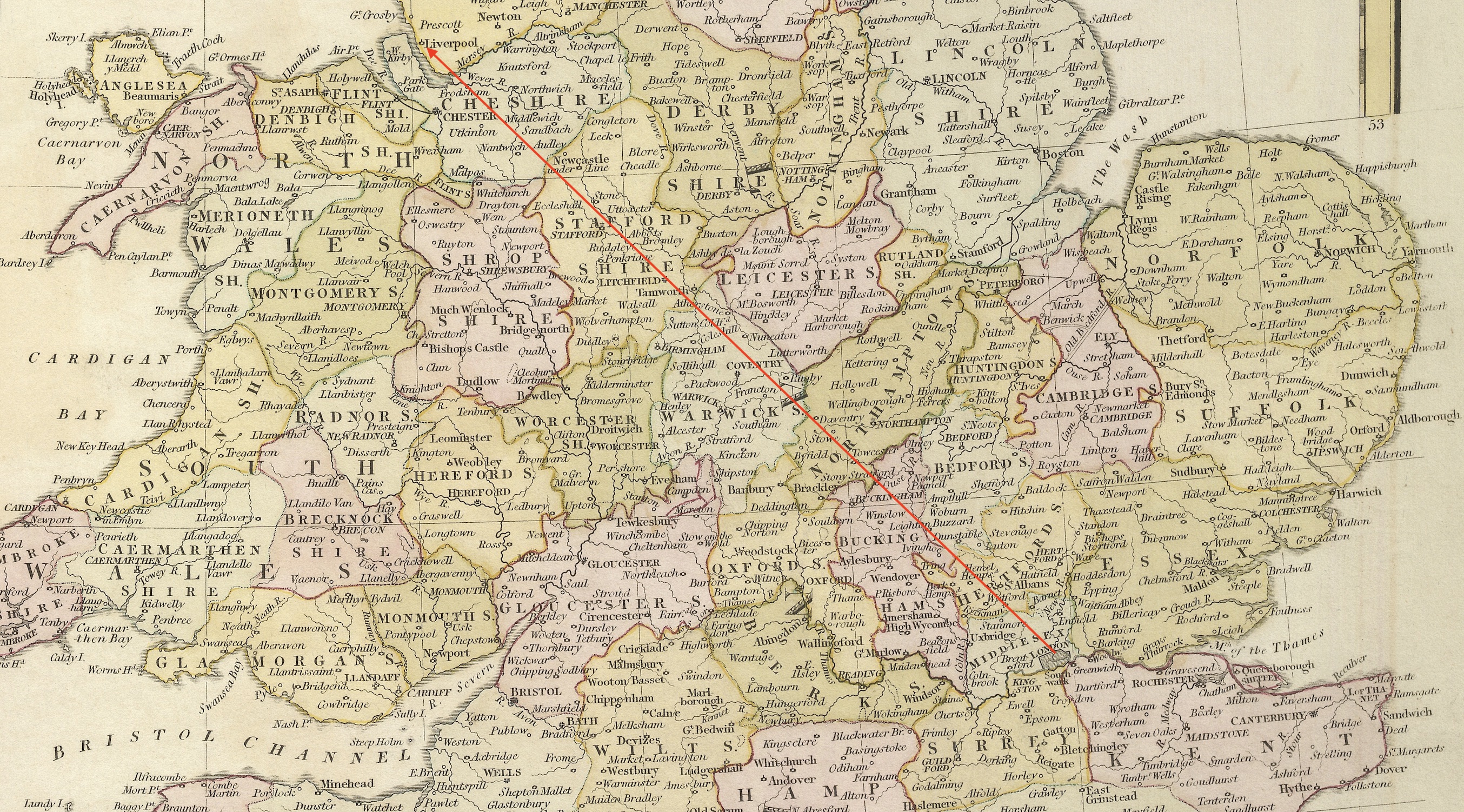

By coach, on 24 June, Keats and Brown leave for Lancaster, where, because of the upcoming parliamentary election, accommodation is not easy to find. During the trip, they do much walking, averaging a testing pace of between 15-20 miles/day. The trip includes taking in the Lake District, climbing Skiddaw and Ben Nevis, visiting the tomb and birthplace of Robert Burns, as well as seeing famous natural sites, ruins, and numerous towns and tiny villages. Blistered feet, smoky cottages, and indifferent fare are also part of the trip.

Keats is often captivated by the landscape, some of which is very new to him—interestingly, Keats is at moments struck by the realization that the imagination cannot surpass actual encounters with, for example, mountains, lakes, chasms, and waterfalls. Keats, too, is often struck by the human landscape, ranging from beautiful young faces to those carved by poverty. Keats feels some fatigue quite early in the trip, and his exertion might have encouraged or made him vulnerable to tuberculosis, which may already have been lingering. By early August, throat troubles stalk him quite seriously.

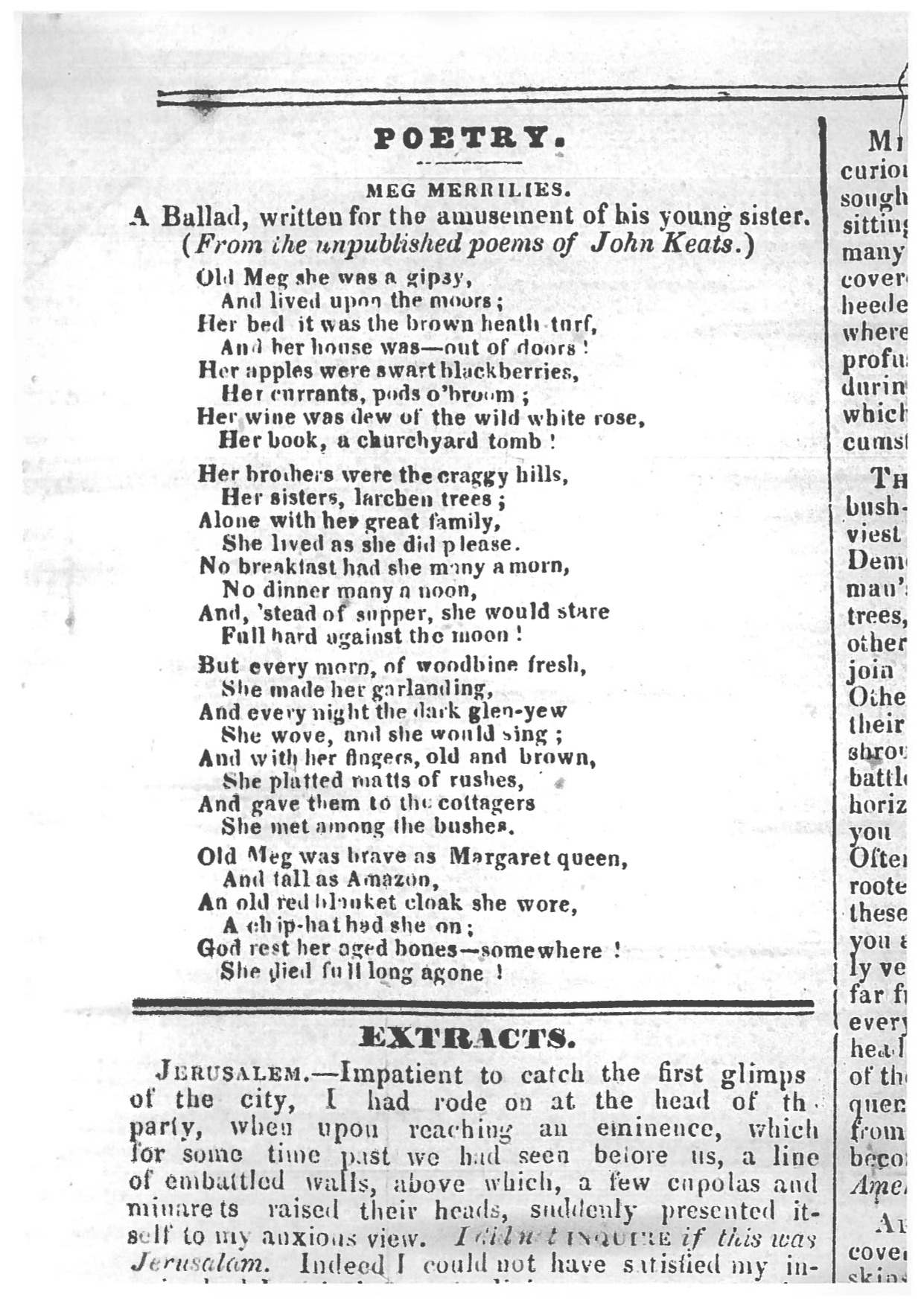

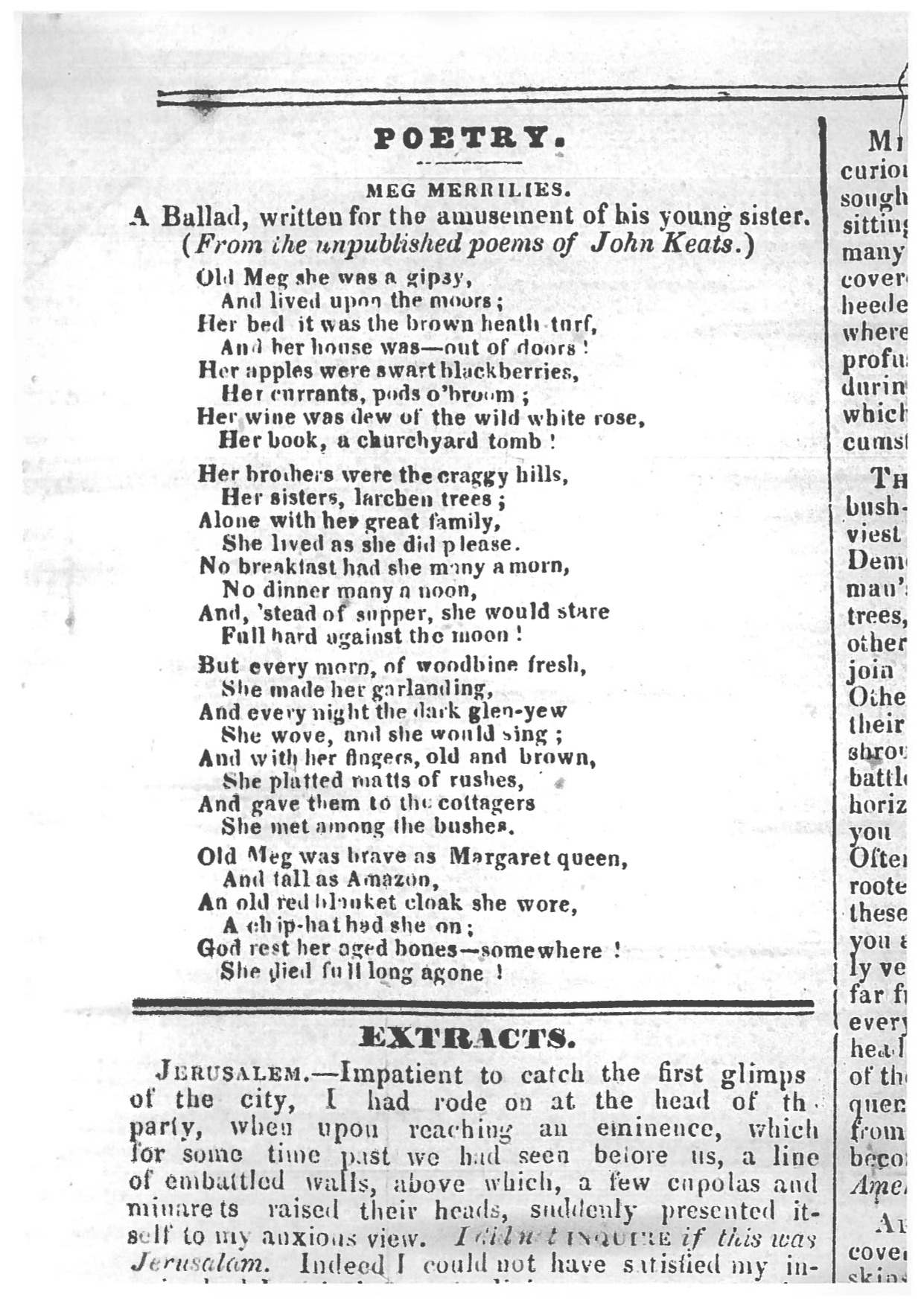

Keats writes a number of poems during the trip—fifteen in total (over 600 lines), ranging from the serious (On Visiting the Tomb of Burns) to the silly (There was a naughty boy). Clearly some of the poetry is written to pass the time by reflecting lightly on local colour, as well as to commemorate natural features, like Ailsa Rock, Fingal’s Cave, or Ben Nevis. Much of the poetry, despite being occasional, does not put on or display an affected, prettified Huntian style, but rather a somewhat listless desire to write something, when in fact he may not be ready to put anything striking or memorable on the page. Nevertheless, Keats’s various moods and mastery of various poetic forms and voices are on display. Perhaps the most interesting poems are those that attempt to understand what exactly Burns represents, especially in light of poetic reputation and fame, which, mainly via Leigh Hunt, is a topic Keats has struggled to come to terms with. Burns also represents the figure of an outsider, something to which Keats relates.

In the background, especially while in the Lake District, but also later, two Wordsworths haunt him: one whose conservative

associations sadden him (this is accented when they arrive in Lancaster at the moment

of a

parliamentary election, with Wordsworth siding with Lord Lowther, the Tory incumbent); and the other who is the great poet of deep

receptiveness and loss, whose unfading, philosophical gaze (seeing into the life of

things,

Tintern Abbey, 50) stands outside of any particular time or

place. One of Keats’s best poems written on the trip in fact derives its sensibility

and form

directly from some of the rustic and forsaken female figures in Wordsworth’s early

poetry, as

well as owing something to Wordsworth’s Lucy poems: Old Meg she was a gipsey. Keats

calls on Wordsworth on 27 June, but he is disappointed

not to find him at home. Keats,

however, is not disappointed by the landscape; in fact, evoking something of a sensibility

for

what we might call the Romantic sublime, he is astonished by the countenance

and

magnitude

of what he sees; he hopes to be able to write poetry that will somehow

capture the meaning of these scenes (letters, 27 June).

Keats is back in Hampstead, via London, by mid-August.

[To view a detailed, interactive mapping of Keats’s walking tour, see Keats’s Northern Walking Tour.]