22 June 1818: Keats’s Northern Expedition Begins

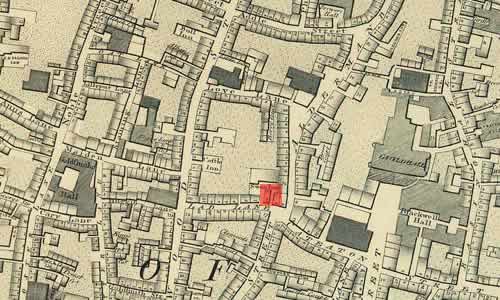

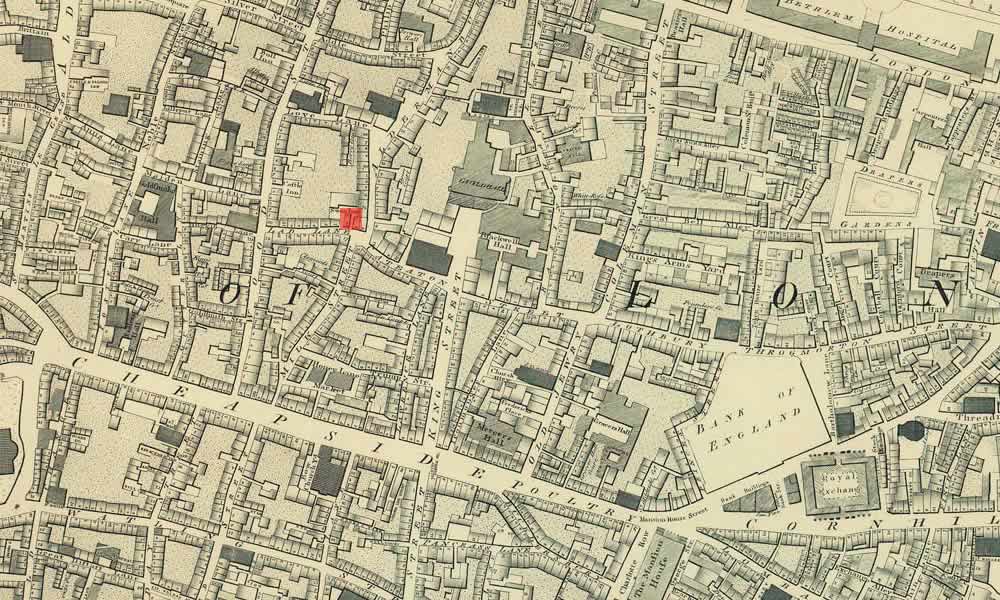

Swan With Two Necks, Lad Lane, London

The Swan With Two Necks is a coaching

inn, from which Keats and his friend Charles Brown begin their walking trip north; Keats

returns mid-August. The first leg takes them to Liverpool (about 200 miles), where

they will

part with Keats’s brother, George, and wife, Georgiana, who, for employment and land, are

emigrating to America.* In a way, it is fortunate—for us—that George and Georgiana

move: Keats

writes a number of long, important, and remarkable letters to America that reveal

much about

his life and thinking—and development as a poet; that is, without these letters, there

would

be significant gaps in our story and understanding of Keats. [To view a detailed mapping

of

Keats’s walking tour, see Keats’s Northern Walking Tour.]

The health of Keats’s other younger brother, Tom, continues to worry Keats, and rightly so: by the end of the year, Tom dies of the so-called family illness, consumption, though Keats left believing Tom’s health was improving. Keats’s own health, too, is not that stable, and on at least one occasion he gets doctor’s orders to stay indoors. The trip north will not help, and eventually only weakens Keats. He continues to draw money in bits and pieces from his estate (managed by the generally unsupportive Richard Abbey), and he never quite knows how much he is entitled to; the sum is actually fairly significant, and knowledge of it would no doubt have calmed some of Keats’s anxieties.

Keats at this time varies in his moods: on one hand, he clearly enjoys the company

he keeps

and in keeping company; yet his skeptical side—revealed to Benjamin Bailey—is one of resignation: Life,

he writes in

context of thinking about his own path and family, must be undergone

(10 June). Keats’s

long poem Endymion, published in late April, begins to

circulate modestly (sales-wise, at least), with a few minor friendly reviews, though,

as we’ll

see below, it won’t be long before him and his poetry will be critically skewered

in a few

influential quarters.

Well, at least Keats has something to do. He begins that walking trip Charles Brown having attempted to articulate a poetic philosophy, one that promotes a speculative mind that conquers bias and uncertainty by welding beauty and truth, and one that values exploration of life’s dark passages with imaginative capabilities. These will set his poetic progress forward.

Two of Keats’s implicit goals for (what Tom

calls) his northern expedition are to experience the landscape of the Lake District

that William Wordsworth so powerfully represents. He

also plans to visit the birthplace of Robert

Burns, and perhaps come to terms with what Burns as a poet might mean relative to his

own poetic identity and aspirations. Keats may want to clear his mind of how he is

perceived

as nothing more than an amiable and infatuated Bardling

sitting at the feet of Leigh Hunt—so writes Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in reviewing Hunt’s collection, Foliage. Keats in fact mentions that he feels

smothered

by such reviews (18 June). The smothering metaphor is apt: in his

poetic identity and direction, Keats by mid-1818 feels strongly he needs to breathe

freely and

independently; even his friends, like John Hamilton

Reynolds and Benjamin Robert Haydon,

advise as much. He needs to work in his own style, though he is never egotistical

enough to

bypass deliberate study of (and to draw from), among others, Spenser (in his early writing career), Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, Dante (in his later

writing), as well as incorporating the literary opinions of Hazlitt.

But the highly poeticized style that marks Endymion is sounded first in June in a

snarkily gleeful review in the British Critic, which, with a little panache, has

great fun re-telling the poem’s gallivanting plot, and suggesting that if it were

not for

Hunt’s bad poetry, Endymion, with its gross slang of voluptuousness,

would be in a class

of its own; the writers of the review have further fun in indexing the review thusly:

Endymion, a monstrously droll poem, analysis of.

Keats would have got the

message, though in September he will be hit with charges of weak poetry and poetic

vulgarity

even harder.

While in some critical contexts we could say that the poetry of Endymion ideologically challenges some

kind of conservative poetic values and styles, there’s also a pretty good chance that

it might

largely be indifferent or just odd poetry; an overly-clever critical spin might be

to call it

transgressive.

Nevertheless what is at work beyond whatever Keats is up to, and what

will strongly implied by a few more aggressively negative reviews to come, is that

the style

of Endymion—enjambed, free-flowing couplets—represents more than a formal affront to

the neoclassical, Augustan closed (end-stopped) couplet (as embodied by Alexander

Pope’s

work), but to values that can be stretched into the political. Keats, as a follower

of Leigh

Hunt, will thus be dragged into theCockney school

of not just poetry, but also

politics. Those unconstrained couplets are thus viewed to represent something not

just

excessive, but at some level enact a threatening liberal impulse.

Well, again, at least toward the end of the month, there is the upcoming expedition

to think

about, which a few months earlier Keats was determined to make into a life-changing

event with

sustaining, transformative memories. At the prodding of Bailey, who is very much interested in literary and philosophical matters, Keats

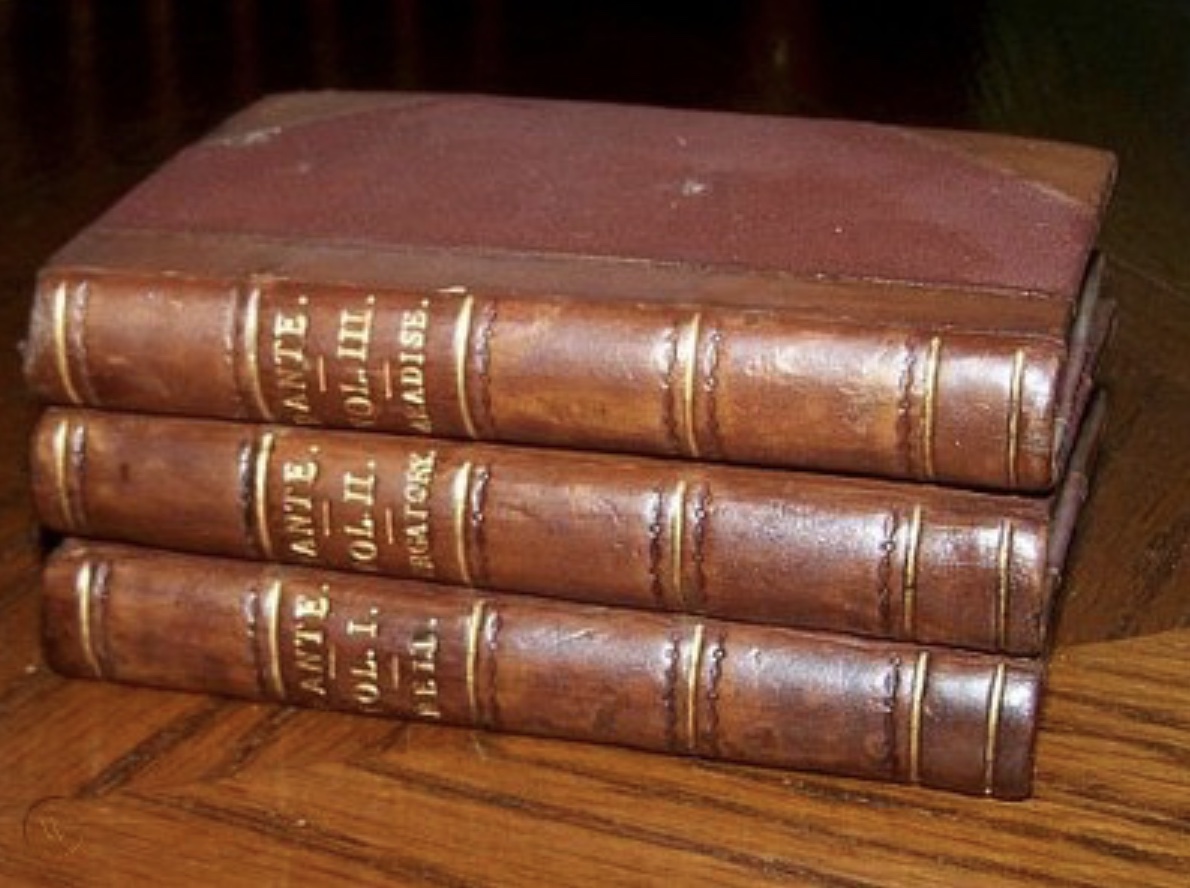

takes Cary’s tiny 3-volume edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy on the trip. (The Rev. Henry Francis Cary’s

translation is published in 1814 by Keats’s future publisher, Taylor & Hessey; Cary

writes

that his little volumes were published in so small in character as to deter a numerous

class of readers from perusing it.

Keats strongly praises a passage from Dante in April

1819 [the meeting with Paulo and Francesca], and later in the year, in September,

he wants to

learn Italian so that he can read Dante.)

Bailey also reviews Endymion (in two parts) over May and June, defending its qualities. We have to recall that Bailey has a minor stake in the poem: Keats and Bailey were together in Oxford in September 1817 while Keats was completing the third book of Endymion, and no doubt they spend some time discussing the poem.

*There is a very good book about George’s life in America: Lawrence M. Crutcher’s George Keats of Kentucky (2012).