15 December 1817: Kean’s Remarkable Richard III: the Development of a Crucial Idea

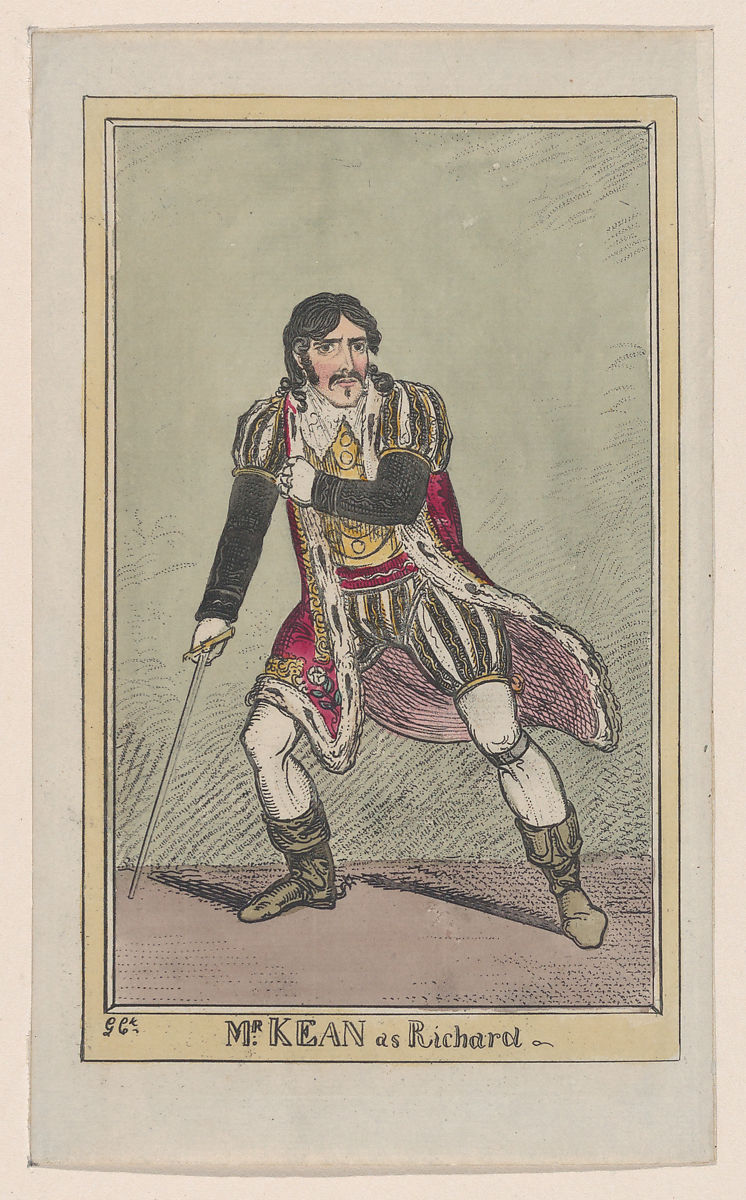

Keats sees Edmund Kean, perhaps the premier (and

certainly the most controversial) actor of the era, perform Shakespeare’s Richard III on

opening night at Drury Lane Theatre. The general consensus is that Kean is brilliant

in the

title role. Keats reports in a letter that Kean acts finely

(21 Dec 1817), and he

discusses Kean with other friends over the next few days. On 21 December, Keats’s

review of

Kean appears in the 21 December edition of The Champion

(Keats is subbing for his friend, John Hamilton

Reynolds, who is on vacation). Keats sees at least part of the play again on 12

January 1818.

Importantly, Keats attempts to understand and articulate what exactly Kean brings to Shakespeare—or more precisely, to Shakespeare’s words. In particular, Keats is

interested in what he perceives as the timeless quality of Kean’s presentation: the

way that

the language (poetry) is more important or pronounced (literally and figuratively)

than the

nominal role. The words, as it were, perform the action; and Kean, in his unique acting

style,

does not deflect the words by superfluous gesture. The shifting and shifty eloquence

of

Richard, who shares his evil intent with us, his audience, is a perfect character

for Keats to

seize upon as possessing camelion

poetic powers. That is, Keats sees (and hears) via

Kean’s representation of the text that language, syllable by syllable, with intense

expression, has its own force and character beyond the particular figure who expresses

the

words. To put it still another way, Keats is struck that Kean’s acting style embodies

language—in ways that come naturally and, to use Keats’s terminology in The Champion review, sensually and with gusto. For Keats, little

does it matter what Richard represents in terms of values or ethics or character;

what matters

(for Keats) is the controlled, penetrating nature of his eloquence; there is splendor

in his

words, made even more so given—and profitably complicated by—his grotesque figure

and vile

intent. What matters is the poetry.

To massage this idea further, an aspect of this idea immediately becomes central to

Keats’s

poetics, and it becomes aspirational in terms of what Keats hopes to eventually achieve

in his

poetry. In fact, in about a year, this leads to some definite, and perhaps stunning,

leaps in

the quality of his poetry. One of Keats’s significant conclusions that both defines

and

propels his progress: that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other

consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration

(letters, 21/27 Dec). Richard’s

(Shakespeare’s) mutating and highly articulate expression of complex, conniving, brutal

evil

is (again, despite Richard’s own gross deformities) beautiful—and therefore, paradoxically,

truthful: his frightening eloquence obliterates

all else. Keats here gleans and

formulates something crucial from watching Kean that he will carry over into his poetics

and

then into his poetry.

Critical elements—in particular, how in superior art all disagreeables evaporate, from

their being in close relationship with Truth & Beauty

(21/27 Dec)—now come together

in the formation of Keats’s epistolary poetics. This has been brewing: Keats’s ideas

are also

extracted from many others, including Benjamin Robert

Haydon and Samuel Taylor Coleridge,

but particularly from William Hazlitt, who, we

note, a few years earlier also praises Kean’s

embodiment of Shakespeare’s dramatic energy

and passion (in his review of Kean in Richard III, in The Examiner, 19 March 1815). Hazlitt, we know, has become a

major influence on Keats’s critical thoughts and tastes, and Keats will profitably

massage

some of Hazlitt’s ideas and opinions.

So, December 1817 is significant moment in Keats’s thinking, with diverse elements

compiling

and intertwining. Besides being forced to articulate Kean’s remarkable qualities and assimilating Hazlitt’s critical insights, Keats recognizes the deficiencies of his recently

completed Endymion, the flaws in certain kinds of art (he succinctly articulates the

deficiency Benjamin West’s painting Death on a Pale Horse in arriving at his key concept of

Negative Capability

—letters, 21/27 Dec), and he meets the most important

poet of the era, William Wordsworth, which

will motivate him to explore and assess the nature of Wordsworth’s genius—and, before

the end

of the following year, he well draw some conclusions about the nature of his own poetical

character, so crucially relative to Wordsworth’s egotistical sublime

(letters, 27 Oct

1818). (See too 20 December 1817).

In short, at the end of 1817, various circumstances and factors accumulate and fuse so that Keats can articulate what kind of poet he wants to become—and what kind of poetry he wants to write. And as mentioned, it will take just over a year for this poetical character to begin to appear in his poetry. [For a compilation of these circumstances and factors, see the conclusions page.]