16-23 April 1817: Endymion, On the Sea,

& Eternal

Poetry: Picturing Young Keats on the Isle of Wight

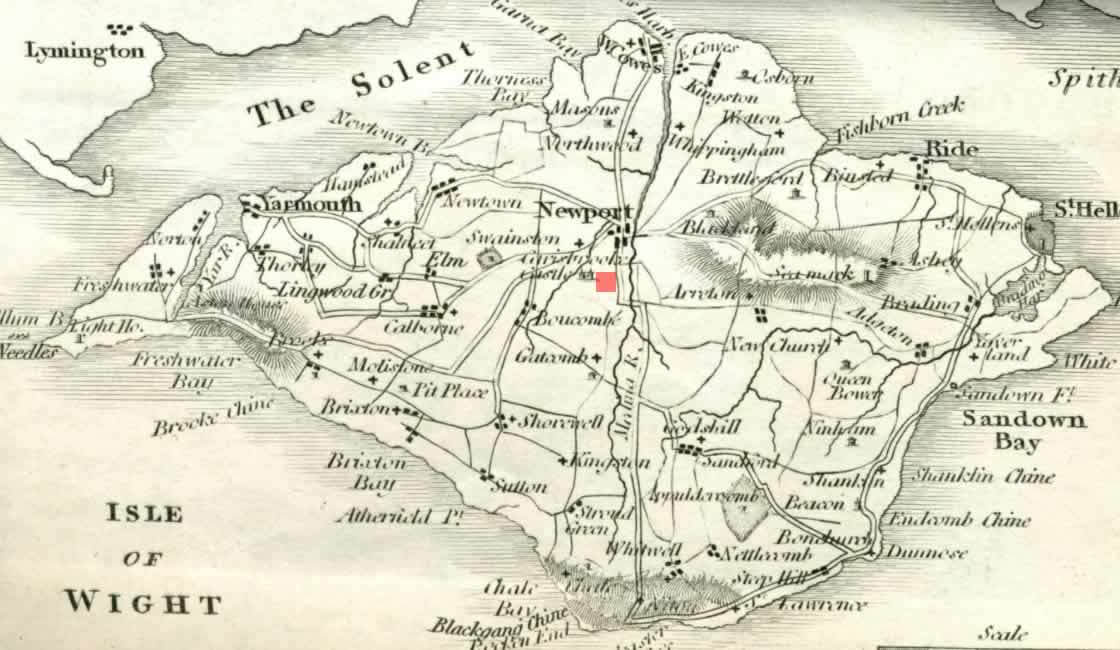

Shanklin and Carisbrooke, Isle of Wight

Via Southampton (on 15 April), Keats is on the Isle of Wight. He arrives at Cowes and then goes to Newport, where he spends the night. He goes to the small village of Shanklin (population about 150). Margate, he finds, is beautiful, but too pricey to stay. Once purely a fishing village, Margate has begun to turn toward being a tourist destination. Keats then moves on to stay inland, at Carisbrooke, for a week (he arrives 17 April).

While on the island, Keats thinks so much about poetry—about being a poet—that he cannot sleep. But in truth, the solitude that Keats seeks by visiting the island quickly translates into loneliness, and after about a week he leaves the island and settles inland at Margate, where his younger brother Tom joins him.

But now: in motivating himself for the daunting task of writing about 4,000 lines on the Endymion myth (gleaned mainly from a classical dictionary), Keats writes to fellow poet and good friend John Hamilton Reynolds about how he has surrounded himself with inspirational material—including the landscape as well as pictures of Milton and Shakespeare, books (including seven volumes of Shakespeare, whose birthday is in a week). Keats writes that he can see Carisbrooke Castle from his window (letters, 17 April). Keats is doubly motivated, since earlier this month he has the assurance from a publisher—Taylor & Hessey—that they will take on his future work.

![Carisbrook[e] Castle, Isle of Wight, 1811. Click to enlarge. Carisbrook[e] Castle, Isle of Wight, 1811. Click to enlarge.](images/carisbrookCastle1811.jpg)

So here we have a picture of young Keats, aged twenty-one: there he sits—impatient, holding his pen, literally looking for inspiration, ready to begin this long, uncertain project. It is a touching scene, in a way. In fact, the situation of a young poet looking for inspiration and confronting imaginative capabilities works itself into Endymion’s blurred, embowered allegory about the pursuit of the ideal. In this way, Endymion is on one level about Keats’s sensualized quest for not just the ideal, but for the poetic ideal—for inspired, enduring, beautiful poetry, for a capable imagination—in the moment of writing Endymion.

Keats purposefully believes that a long poem will, in effect, prove his poetic worth—not

to

mention his determination to take on the mantle of poet. While waiting for creativity

to lift

him, he sends Reynolds an indifferent but

enthusiastic sonnet—On the

Sea—that includes the incapacitated line, O ye who have your eyeballs vext and

tir’d / Feast them on the wideness of the Sea [. . .]

(letters, 17, 18 April 1817). That

the poem is inspired by a line from King Lear does not raise

its quality, but perhaps more importantly we begin to get the sense that, for Keats,

Shakespeare has to become not just a figure to venerate, but one to emulate.

Keats begins his trip full of strong encouragement from another friend, the well-known

historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon.

Haydon is impressed—touched, even—that Keats (like him) is so conscious of a higher

calling.

Keats reports that Haydon has told him that it is necessary that he should be alone to

improve myself

(reported to Reynolds, 9

March 1817). Keats also begins his trip feeling he needs to find his way without the

influence

of others—by this, he mainly means his London circle of friends, and perhaps most

significantly, Leigh Hunt. In a few weeks, Keats

will in fact condemn Hunt’s great sin of deluding himself that he is a great poet

(letters, 11

May).

Importantly, Keats makes a strong and precarious declaration of purpose to Reynolds: I find that I cannot exist without poetry—without

eternal poetry—half the day will not do—the whole of it—[. . .],

while also citing lines

from Spenser about how great intent, / Can

never rest

until it creates something great and eternal (letters, 18 April). For Keats,

his life is, as it were, on the line—the line of poetry.

On 8 May, Haydon writes to Keats in Margate.

Haydon passionately encourages him: God bless you My dear Keats go on, don’t despair,

collect incidents, study characters, read Shakespeare and trust in Providence.

A good part of this is sound advice: in

reading and in deliberately studying Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth in particular, Keats will make

significant progress, especially in understanding the qualities of great poetry—the

poetic

character. He comes to a point where he can make particularized critical judgments

about the

value and significance of respective writers and their work.

Such focused study also weans him away from easier, incidental subjects as well as

from a

tone that at moments too openly aims to entertain and to encourage sociability, rather

than

strive for deeper, artful, and timeless subjects. But Keats writes back to Haydon

that he is

distracted by a few things, including (and as usual) Money Troubles.

He also

experiences a bout of what he calls a horrid Morbidity of Temperament

that shows up at

intervals—what we today might call nervous anxiety or mild depression (letters, 11

May). This

comes and goes during his adult life, but it is likely more a dispositional or character

trait

than a medicalized condition to be pathologized. At any rate, moving forward with

Endymion does not at

this point come easily, though overall his determination and pacing is admirable.

Using his

own guiding terms of reference for his project, he does indeed manage to take one

bare

circumstance and fill it with poetry—4,050 lines, to be exact. But no one said it

had to be

great poetry, least alone Keats; it just has to be done, learned from, and left behind.

In the end, then, Keats comes to hold an ambivalent attitude toward his long, pastoral

romance. While he sees it necessary as a sustained gesture of dedication, endurance,

resourceful imagination, and independence, on another level he recognizes that it

is in some

ways an ill-considered work—a failure he would be happy to rewrite or, better yet,

unwrite.

In the Preface

he eventually writes for the poem almost a year after beginning it, he pleads for

critical

lenience in judging the poem’s literary worth, while regretfully drawing attention

to how the

poem signals great inexperience, immaturity, and every error denoting a feverish attempt,

rather than a deed accomplished.

Keats is all too right. And while his humility and

critical self-awareness is admirable, it also exposes him and his work to criticism

from

certain influential reviewing quarters. A possible translation of the preface: This is the

work of a young, inexperienced poet, so please take it easy on me. I may come back

to Greek

myth for inspiration, but by then I hope I will be a more capable, developed poet. In

fact, Keats does come back to myth at a later stage in his writing—via the Hyperion

story—but

in a style that starkly shows a remarkable development in his poetry.

Two years later, from late June 1819 until the second week of August, Keats returns to the Isle of Wight, and is in very different circumstances: Tom is dead, the poem he is preparing to begin now April 1817 has been published (in 1818), he is not alone, and he has some immediate writing prospects in co-authoring a play; but though he doesn’t know it, almost all of his best poetry, written earlier in 1819, is behind him. He will also have met, and fallen in love with, a certain Fanny Brawne.