14 April 1817: Endymion: A Test of Perseverance & the Lurking Keatsian Question

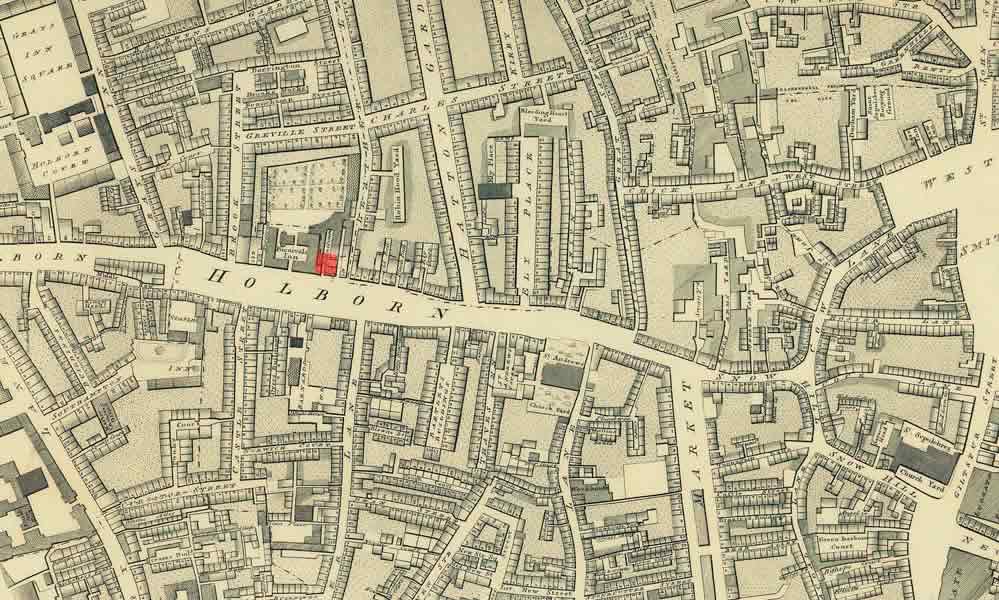

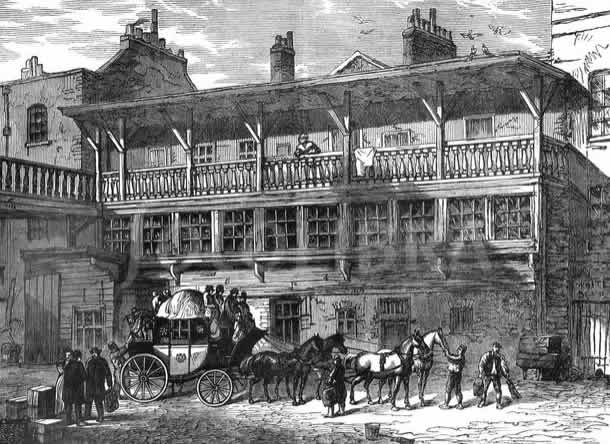

Bell & Crown, Holborn

The Bell & Crown, Holborn: Where Keats and his brothers get together before Keats sets off on a writing journey with hopes to begin a self-set task: to write a very long poem in order to prove himself a poet. He sets off by carriage on a cold ride to Southampton. Twenty-one-year-old Keats takes inspiration with which to surround himself—mainly books, but also some pictures. He also takes with him the knowledge that the publishers Taylor & Hessey have just agreed to publish any subsequent poetry he writes. This itself must have pushed Keats forward: someone believes in his work, someone wants his work.

By 15 April, Keats makes it to the Isle of Wight. After one night in Newport, he travels to Shanklin, which, though beautiful, is a little expensive; he moves on to cheaper and smaller Carisbrooke. He is enthused about a picture of Shakespeare he discovers in the hallway of where he stays. It is fitting to have The Bard close by. Keats probably spends just over a week on the island before moving on to Margate—in search, as it were, for continued inspiration and motivation.

As mentioned, Keats’s trip is mainly about his determination to prove himself by writing

this

long pastoral romance—in this case, more than 4,000 words based on one bare

circumstance

that he will fill

with poetry (Keats quoting himself from spring

1817 in a letter written 8 Oct 1817). He begins the poem about the third week of April.

The

bare circumstance

: a heavenly moon goddess, Diana, falls in love with an earthly (but

good looking) shepherd, Endymion. (Keats describes the poem’s plot in a letter to

his sister,

Fanny, 10 Sept. 1817). Keats had already taken

up the story at the end of his I stood tip-toe poem,

completed at the end of 1816 and published as the first poem in Poems,

by John Keats.The tip-toe poem was provisionally titled Endymion.

Endymion takes up

much of Keats’s poetic energies for about year. The poem, however, is largely ineffectual—and

more an exercise of perseverance rather than the execution of excellence. It is a

poem of

confused ambitions and vague allegory: key Keatsian question lurking beneath the poem—Can

the

imagination know or create truth?—are overweighted by embedded poetic fluff. Indeed,

at times

the poem does feel like filling, though Keats suggests that true Lovers of Poetry

like

a little Region to wander in,

a place where they may pick and choose

from an

abundance of images

(letters, 8 Oct 1818). In a way, the form (couplets) partly

undermines a certain amount of seriousness of tone, as do descriptions (those images

)

that often extend beyond their necessity. Keats is aware that he has the weakness

to be

over-charmed by rhyme.

As a confused quest poem for the ideal, the poem’s allegory holds up only somewhat

evenly. Keats

comes to know as much, but he also realizes that his poetic progress can take the

form of both

foundering and floundering: as he looks back upon Endymion, he

writes that he was never afraid of failure; for I would sooner fail than not be among the

greatest

(letters, 8 Oct 1818). Importantly, in revising and correcting Endymion for publication (in about a year from now), Keats works to

a key moment when he can critically assess his future poetic directions in light of

Endymion’s limited qualities, sketchy scope, and original

motivation. The best we can do: In terms of Keats’s poetic progress, the poem acts

out, with

some persistence and rambling fearlessness, the drama of a questing imagination.