April 1817: Keats & Sovereign Shakespeare

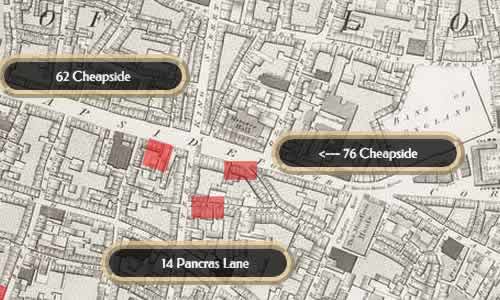

62 Cheapside, London

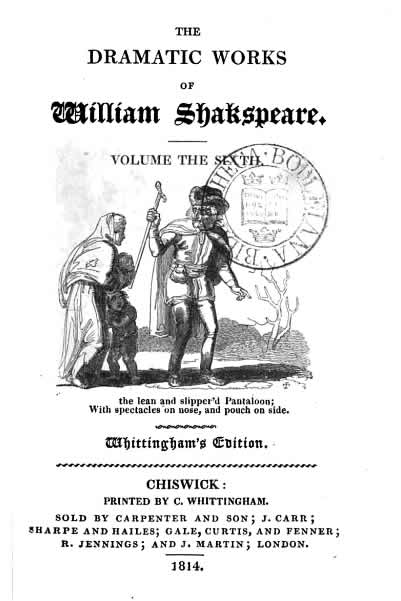

The premises of Robert Jennings, publisher. Where Keats buys a 7-volume edition of Shakespeare’s works (the 1814 Whittingham edition; Keats at some point also owns an 1808 facsimile edition of Shakespeare’s first folio). Keats shortly travels with these books, hoping for inspiration to begin his trial of invention and perseverance—and what we know as the long, meandering romance, Endymion. Keats feels he needs to get away from the London crowd in order to concentrate on proving his independent poetic worth and the mantle of poet.

Shakespeare remains Keats’s primary model in the development of a style and tone that bypasses egoism, indulgent subjectivity, affectation, and pedantry. There are possible two cardinal points that evolve from his very deliberate study of Shakespeare: first, that the truth in poetry, regardless of its topic or perspective, will be in its beauty; and second, that complexity, uncertainty, and paradox are negatively capable positions of feeling and thought—and to be embraced. Mainly through Shakespeare, Keats sees that reasoning and logic are misleading and confining as ways to know anything. What will come to especially intrigue Keats is how Shakespeare can assume any character, thought, feeling, or action without compromising the poetic grandeur, grace, or intensity—full but controlled absorption by the subject is the desired effect, despite shifting perspectives and mutability. (This will take Keats to his determining theory of Negative Capability.) That is, the subject is the thing, and the poet’s job is find a language and voice—intense but not over-reaching, natural yet controlled—to, as it were, embody the subject. Poetic incarnation, one might say. Keats, in fact, reminds us to turn our attentions to Shakespeare the poet within his plays, and how he uses characters to fully lyricize the subjects that, so often, inhabit them, rather than the inverse. This is key to Keats’s understanding of Shakespeare, and thus to our understanding of Keats.

We see, then, with ever-increasing purposefulness, Keats explore and anatomize Shakespeare during the course of his poetic

progress, with discussion of Shakespeare spilling over into contexts with friends

and family.

Importantly, Keats studies what one of the leading critics of era, and a friend of

his, William Hazlitt, writes about the specific nature

Shakespeare’s genius, and whose ideas about Shakespeare’s qualities and genius are

profitably

massaged by Keats. Then there is also Keats’s very close friend, the historical painter

Benjamin Robert Haydon (himself crazy about

Shakespeare), who strongly advises young Keats to read Shakespeare

(letters, 8 May

1817). As Haydon will record in his diary after Keats passes away, I have enjoyed

Shakespeare more with Keats than with any other Human creature.

Keats at one point tells

his brother George that, when apart, they should

both read some Shakespeare at the same time (letters, 16 Dec 1818). Amazingly, Keats

refers

both directly and indirectly to over thirty of Shakespeare’s plays in his letters.

Hamlet and King Lear are

particularly close to him, with Midsummer Night’s Dream, Othello, Henry IV (I), and The Tempest always lurking in his thoughts and falling easily into

letters to his friends and family.

At different points, Keats writes that Shakespeare is enough for us

(11 May 1817) and a great wonder (14 Aug 1819).

As Keats moves toward writing mature poetry, he begins to feel content

: on 27 February

1818 he can write, for thank God I can read and perhaps understand Shakespeare to his

depths.

This is a remarkable statement of accomplishment, confidence, and, implicitly,

purpose; putting that understanding into poetic practice will take another year. For

Keats,

then, Shakespeare is the great Presider

(letters, 11 May). In what way? As Keats notes

in his marginalia in his facsimile of Shakespeare’s first folio, The Genius of Shakespeare

is an innate universality

—and this, in terms of Keats’s poetic progress, marks what he

hopes will be his achievement.

And when his health prevents much writing, and when the world’s brutality, the loss

of his

love, and death crowd upon him, and when he is at a loss for how to express himself,

Keats

writes, Shakespeare always sums up matters in the most sovereign manner

(letters, to

Fanny Brawne, Aug 1820).

One other person besides Hazlitt might be mentioned in assessing Keats’s crucial engagement with Shakespeare: the actor Edmund Kean. Keats is forcibly struck by how Kean, in his style of acting, embodies Shakespeare’s words—the words, as it were, do the acting and perform the drama, and Kean, for Keats, is a vessel for words; this is an idea that Keats will in fact strive toward in his own (and best) work: to make the words themselves forms of coordinated, controlled action. [For more on Keats and Kean, see 15 December 1817.]