3 March 1817: Keats’s First Collection, Poems, is Published

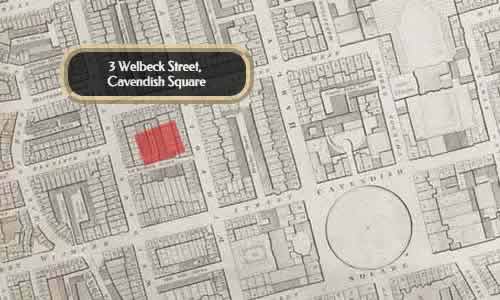

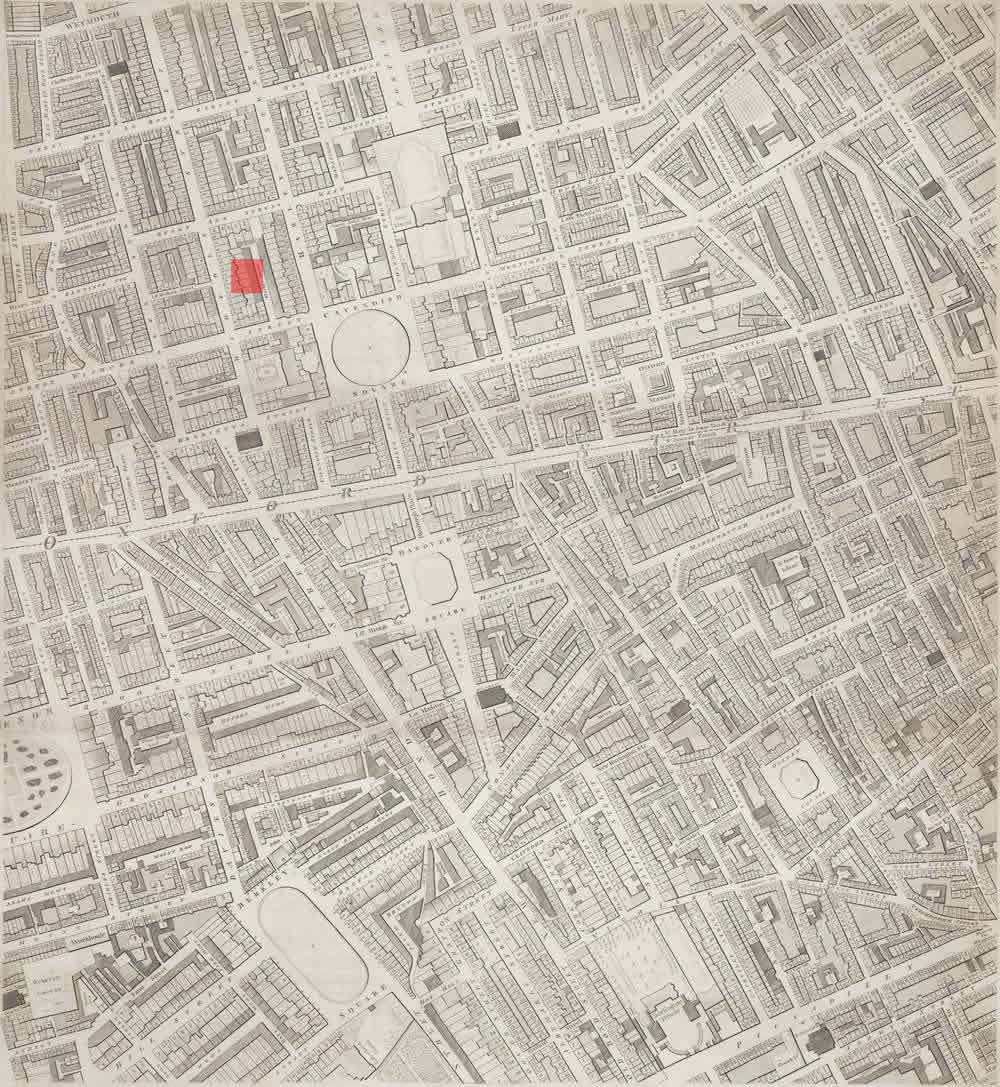

3 Welbeck Street, Cavendish Square, London

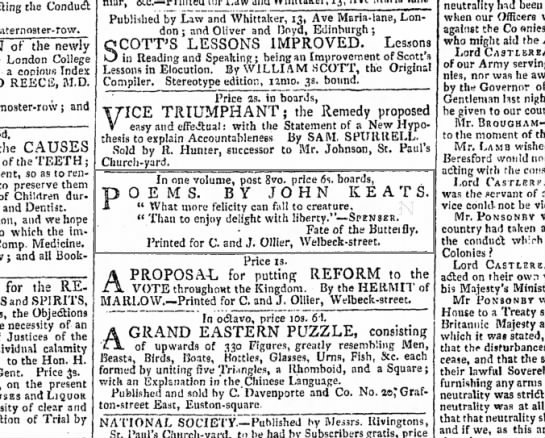

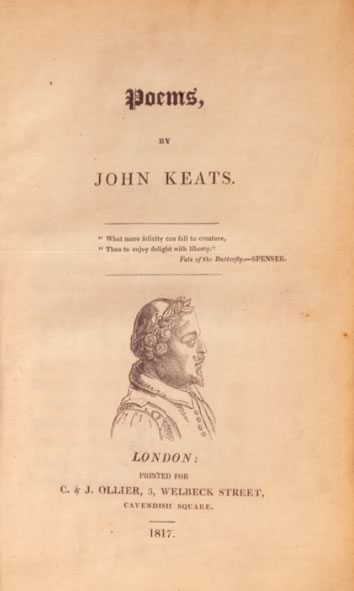

Keats, aged twenty-one, publishes his first collection—Poems, by John

Keats—with the recently-formed C. &

J. Ollier; copies are published either probably

7 or 10 March 1817, though a few copies were available a few days earlier. Charles Cowden Clarke and Leigh Hunt recommend Keats to the Ollier brothers (Charles and James),

whose offices later move from 3 Welbeck Street to 14 Vere Street. Keats picks up the

cost of

publication, and the inexperienced Olliers hope to earn a small commission on sales.

It would

not have been unusual for an inexperienced or unknown author to subsidize or pay for

a first

book (it still happens today, of course, in the name of vanity

), but Keats was very keen to see

himself in print. Keats’s acquaintance and implicit poetic rival Percy Shelley (who also falls within the Hunt circle) will

generously pick of costs for adverting this volume by the fully unknown Keats, though

the

notices did nothing to garner sales. Coincidently, this is the date that, at least

officially,

Keats’s position of a surgical dresser ends.

Keats’s volume is, for the most part, quite weak—a few poems are a little embarrassing, and a few overly personal or trivial. This, though, a necessary part of Keats’s poetic development. He can put his juvenilia behind him. He’s out and running, so to speak.

If anything, the collection does show some versatility as the young poet makes marks

his

first entry into the crowded poetic marketplace: it contains thirty-one poems, including

three

epistles and seventeen sonnets—all sandwiched between two longer and marginally better

but

meandering poems, I stood tip-toe upon a little

hill and Sleep

and Poetry. By far the most famous poem in the volume is the ever-anthologized

sonnet On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer, although it too, despite its balanced

drama and fairly settled tone, exhibits the weaknesses of a wide-eyed, inexperienced

poet

finding inspiration and looking toward an uncertain future. In short, the insecure

but

striving message in many poems is Keats’s desire to be a great poet—he pictures himself

reading, writing, and looking for inspiration. A few years later, when Keats is precariously

ill and he no longer writes poetry, Keats will knowingly refer to Poems as containing my first-blights

(letters, 16 Aug 1820), and of course

he’s mainly right. As for the Olliers, they came to regret publishing the volume,

and they

even felt that they accept returns for refund rather than face ridicule.

The rather sloppily produced volume is dedicated to Leigh

Hunt—Keats’s unofficial mentor at the time. Some reviewers come to unfavorably point

out Hunt’s influence on the poetry. They are right, and Keats begins to take note.

A few

friends, like Benjamin Robert Haydon and John Hamilton Reynolds, also point to Hunt’s

unfortunate sway directly to Keats. One way to characterize Hunt’s poetry (though

formally he

was a remarkably versatile poet) might be to suggest, a little oddly, that it is somewhat

too

charming, a little too mannered, a little too leafy, so to speak—in short over-poetical.

To

progress, Keats needs to go in a different direction, one suited to his own temper,

gifts, and

aspirations: poetry that does not parade its poetical nature, but instead embodies

and

reflects its subject. Keats will come to recognize that Hunt is an indifferent poet,

and that,

worse yet, Hunt’s estimation of his poetic prowess is greatly inflated. Later, as

Keats comes

to terms with what he calls my own strength and weakness

while acknowledging he was

never afraid of failure

—and when he is on the verge composing his greatest poetry—he

declares, I will write independently

(letters, 8 Oct 1818).

For his part, Hunt likes to see himself as the discoverer of Keats, which in a way he is. By fully advertising his poetic affiliation with Hunt in Poems, Keats (perhaps a little naively) also signals political affiliation that would solicit automatic dismissal from certain fairly powerful Tory reviewing circles—little did Keats know how strong this dismissal this would be, not to mention how legendary it would become in the construction of the Keats narrative. In the future, Keats will not have his poetry wear its politics quite so thickly. Other principles and poetic theories will begin to guide Keats: the desire to write enduring poetry; a seeking of subjects to represent the complex relationship between truth, beauty, and the imagination; the taking on the timeless and paradoxical engagement of human consciousness with art, nature, and mortality; and in doing so, Keats will create his own critical and poetic vocabulary—he becomes, as it were, Keatsian, but that’s to come.

Meanwhile, and interestingly, when Hunt himself reviews Keats’s volume in June, he will, a little condescendingly, point to Keats’s youth and inexperience in the ways of the world. Hunt will also point to the poetry’s discordant and faulty employment of overly impassioned and poeticized detail. Hunt is right in those latter criticisms, but, ironically, these were more or less the charges sometimes levelled against Hunt’s own poetry. All the while, in terms of Keats’s poetic progress, the young poet will not stand still: he will be searching for greater, more enduring poetic models, whom he will study, eventually emulate, and then innovate upon—and, in the end, by 1819, his final year of composition, models he will in some cases surpass in establishing his own originality.

The Olliers will also go on to publish works by Hunt, Percy Shelley, Thomas Love Peacock, and Charles Lamb. But Keats almost immediately drops the Olliers after Poems is released (no doubt in the future he wants not to pay for publication costs). Subsequently, he publishes his other two books (in 1818 and 1820) with Taylor & Hessey, while they also acquire publishing rights of Poems. In September 1820, when Keats is very sick and virtually penniless (he is unaware of significant funds he has right to held in Chancery), Keats sells copyright to all three books to Taylor & Hessey. He needs the money in the vain hope of recovering his collapsing health by moving to Italy.