30 December 1816: Leigh Hunt & Early Poetic Strivings

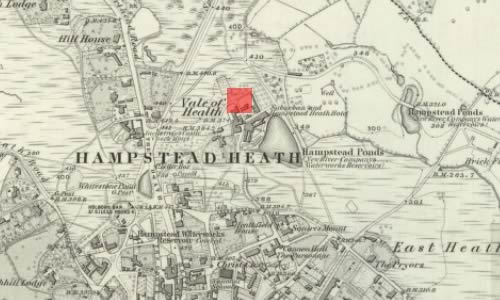

The Vale of Health, Hampstead

The Vale of Health, Hampstead: Leigh Hunt’s cottage. Since mid-October 1816, Hunt—well-known poet, critic, and celebrity journalist—has, in a way, taken twenty-year-old Keats under his wing in a role that spreads between supporter and mentor, and rightfully so given Hunt’s significant experience and reputation relative to the unknown and somewhat naive Keats. Hunt takes to Keats instantly, and he greatly believes in the young poet’s gifts; he will do so throughout Keats’s short writing career.

We have to remember, too, that Hunt is a hero-martyr for Keats. In February 1815, more than a year and a half before they meet, Keats in Written on the Day That Mr. Leigh Hunt Left Prison poetically celebrates Hunt as a high-flying immortal spirit, sharing poetic prowess with the likes of Spenser and Milton. Hunt had spent two years in jail for libeling the Prince Regent, though Hunt famously turned his cell into a kind of literary salon, and was also given some a little outdoor space to cultivate; for a while, his family lived with him (see the image below). He received many famous literary and political guests while in jail—a kind of prison-house coterie.

Through Hunt, Keats is immediately drawn into a network of writers, critics, artists, poets, and publishers who are strongly associated with London’s progressive-liberal camp.* In his journal The Examiner, Hunt has just published some of Keats’s poetry, as well as a short article that announces Keats as one of the new Young Poets. Hunt, then, announces Keats to, so to speak, the world. Well, at least Hunt’s world.

In the short term, association with Hunt and The Examiner comes to haunt Keats, since it opens up

attacks—personal, poetical, political—on Keats as a member of the so-called The Cockney

School of Poetry.

The specific Cockney

label comes about with attacks on Hunt as

its chief Doctor and Professor,

beginning Blackwood’s

Edinburgh Magazine of October 1817, and was chosen to dismissively clump together

Hunt and his so-called followers, and to associate them with vulgarity, effeminacy,

and

inferior social rank. There is also an implicit competition between Edinburgh and

London as

cultural centres.

On this day, 30 December 1816, in a 15-minute friendly sonnet-writing competition

with Hunt (who seemed to love such things), to be on the

grasshopper and cricket, Keats writes the reasonably accomplished On the Grasshopper and

Cricket. He apparently wins the competition based, in part, on completing on

time. Keats’s poem has the fairly subtle and memorable opening line—The poetry of earth is

never dead

—that Hunt appreciates, perhaps because it airs so naturally. Keats also

takes the ostensible subject to levels that connect nature and art, and the human

imagination

with the ambient scene. The ending of the poem, with its focus on a stove on a frosty,

silent

winter evening, profitably evokes Coleridge’s

remarkable conversation poem, Frost at Midnight.

Noticeably, Hunt’s poem on the

subject, though technically sound, is embedded with domestic sentimentalism and prettified

phrasing—for example, the grasshopper is called (with a little lame personification)

a

Green little vaulter in the sunny grass.

As for Hunt’s cricket—well, in Huntian

style, its chirpy chirping is apparently a tricksome tune.

Unlike Keats’s poem, Hunt’s

is hardly expansive.

Although the circumstances for these two poems is not overly crucial, Keats will learn to avoid this style of writing and circumstance for composition in his progress over the next few years—the habit of writing poetry as an act of sociability and in the spirit of friendly entertainment that Hunt embraces and promotes. The incident also tells us about the closeness of Keats and Hunt at this time. Hunt will in fact publish the two poems together in The Examiner on 21 September 1817, once more culturally linking Hunt and Keats.

In December, we know that Keats also, at the very least, writes To G. A. W.,

To Kosciusko,

Written in Disgust of Vulgar Superstition, and perhaps On Receiving a Laurel Crown

from Leigh Hunt and To the Ladies Who Saw Me

Crown’d. These last two poems might also have been written in sonnet-writing

competitions involving Hunt, and they may have been

written in early 1817. In Vulgar

Superstition we find Keats a little worked up about religion, noting its

negative, hypocritical callings: under religion’s gloomy sermonizing, the mind of man is

closely bound / In some black spell.

[For an

overview of Keats’s ideas about religion, see 18 December

1795.]

In December, Keats also completes two longer and substantial poems that will begin and end his 1817 collection, Poems, by John Keats: I stood tip-toe upon a little hill and Sleep and Poetry. Both poems in slightly different ways (yet with indifferent results) are, at best, youthful, harmless strivings that advertise a poet in-the-making; at worse, they are largely aimless and ineffectual. Like some of his other 1815-1816 poetry, these two poems mull over—perhaps even obsess over—fame and Keats’s desire to be a great poet. They are largely uninspired poems about a young poet’s search for inspiration. Further, there is much Huntian affected phrasing; too frequently the rhyme, rather than reason, determines direction and turn of phrase. Like Hunt’s poetic style of this period (particularly in his long The Story of Rimini), Keats’s form in these poems does challenge a poetic tradition (mainly eighteenth century) by loosening the stop-start structure of the heroic couplet, but challenge alone does not ensure that it works very well. It will take much deliberate study to move beyond this quasi-descriptive genre, but within about two years, Keats will curb his youthful enthusiasm in favor of a voice that self-critically controls tensions in equally controlled lyrical styles and voices.

View at Hampsteadby Richard Corbould, 1806 (Victoria and Albert Museum 522-1870). Click to enlarge.

December 1816 can be used to mark Keats’s decision to become a full-time poet, even with a possible medical career lurking in the background into early 1817. The manager of the family estate’s money will not be happy, especially given that significant funds had been spent on Keats’s medical training.

*See here for Hunt’s key place as a node in Keats’s social network.