14/15 December 1816: A Whoreson Night

& A Too-tippy I stood

tip-toe

9 Providence Place, London

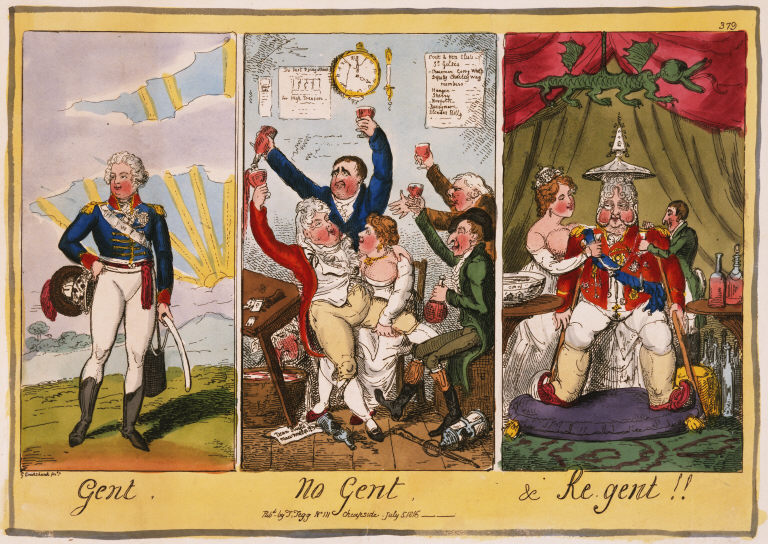

Regency London: The years from 1811 to 1820 are called The Regency, or Regency period, marked by George, Prince of Wales, becoming the Prince Regent. George’s father, King George III, has been officially declared mentally incapable, and therefore his son assumes (is delegated) the role of King—hence, the Prince Regent and the Regency Period. The era is marked by complicated historical, cultural, economic, political events—such as the defeat of Napoleon (1815, with the Battle of Waterloo), the 1815 Corn Law, Luddite activities (1811-1812), the Spa Field riot (1816), the important trials of William Hone for sedition and blasphemy (1817), political activism (for example, Hannah More, James Stephen, William Wilberforce), the Peterloo Massacre (1819), the Cato Street conspiracy (1820), and the rise of both Evangelicalism and humanitarianism. Then there was also the Regency London social and cultural scene, known for its extreme pursuits of fashion (like dandyism), pleasure-seeking, décor, theatre, sporting events, the fine arts, and architecture (for example, the work of John Nash). For many, this was a condition of utter excess during hard times, and Keats would have had front-line exposure to it.

Keats could enjoy some of social mixing downtown in Regency London. Here he is at

the

residence of Thomas Richards, where Keats says

that he spends so whoreson a Night that I stopped there all the next day

(writing to

his friend, Charles Cowden Clarke, 17 Dec 1816).

What this means is not perfectly clear, but it certainly suggests the evening involved

much

drinking and a pretty good hangover. Richards’ brother, Charles, is the printer of Keats’s first volume of verse

(published by the Ollier brothers), the 1817

Poems, and like Keats and Clarke, was a student and Enfield.

Richards is also a part-time theatre reviewer for The

Examiner.

During this week, Keats likely completes I stood tip-toe upon a little hill. It becomes the opening poem for the 1817 volume, and so Keats must have thought something of its poetic worth. In December 1816, Keats is also publicly certified (listed) as a apothecary, has his thus-far best sonnet published (On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer), has an article partly about him published, and has a face-mask made by an established artist (Benjamin Robert Haydon). Perhaps some of this contributes to his celebration—and inebriation—at the Richards residence.

Like much of his early poetry, I stood tip-toe is mainly

about Keats’s desire to be an inspired poet—or any kind of poet, for that matter.

Here, this

desire is acted upon by, it seems, just arbitrarily looking around the landscape (on

tip-toe,

which might be tiring after a while) and hoping for the best. This situation is handled

with

little originality, efficiency in phrasing, or imaginative power. What the speaker

looks at in

the poem—mainly an accidental catalog of drooping buds, long grasses, passionate flowers,

skittish minnows, etc.—is randomly presented with equally random and often affected

rhymes.

Some things do not make much sense; even some poetic clichés are odd. For example,

Keats

writes, The clouds were pure and white as flocks new shorn

(8), but freshly sheared

sheep are neither white nor cloud-like in the fluffy sense—not to mention that now

that they

are shaven, their pureness is a little dubious.

The envisioned landscape the speaker also seems to take us to at one point in the poem is not unlike the landscape the speaker actually stands tip-toe upon, though presumably the tip-toeing has stopped so that the speaker can either move around to note or envision other things required of an aspiring young poet.

And in the wandering, wayward spirit of the speaker’s imagination, he does indeed

get around:

he wonders what it might be like to lead a nimble-toed, auburn-haired, blushing maiden

over a

brook (95-106). But, alas, it cannot be: this coy little daydream abruptly ends, and

the

poem’s haphazard direction is revealed in the lame line immediately following: What

next?

(107). Indeed! And then, it is back to the primroses and whatever else is supposed

to create or inspire a sweet poet

(116). What he really wonders about is what inspired

the first poet to imagine all those classical pastoral figures in the first place.

Maybe he

stood upon a hill (194-95). So perhaps, here too, our speaker, will be born a poet

(241). Or

not—or not yet.

There is also in Keats’s poem a kind of unprofitable reproduction of parts of a poem

that

early Keats thought highly of: Leigh Hunt’s

The Story of Rimini (1816), where, in a passage of Canto III,

we find a extended, random, and heavily poeticized cataloging of almost everything

you might

possibly see in an overgrown garden—all of it, as in Keats’s poem, bowery, flowery,

babbling,

and leafy (see lines 380-533 in particular). Keats knew this passage from Hunt’s poem

very

well, since he in fact uses one line from it in—Places of nestling green for poets made

(430)—as the epigraph for his tip-toe poem.

In short, I stood tip-toe

does not work all that well, and if the poem could speak

(well, it sort of does), it might say that it not sure what kind of poem it is. Lyric?

Apostrophe? Loco-descriptive? Transporting vision? Yes, with all that sweetness, lightness,

softness, loveliness, greenery, and looking about, the poem is vaguely and innocuously

agreeable, despite its identity crisis. And at best, its strivings are somewhat touching,

since (like much of his early poetry) these strivings translate to I want to be a poet—but

where, and how? Where do I find inspiration? In nature? In the imagination? Through

vision? But again, relatively speaking, these are early days.

In just about a year, this kind of benign, tip-toeing, poetic meandering and wandering—we

could call it poetry lite

—gets left behind: in developing a sophisticated poetics,

Keats begins to take on and deliberately study poets like Milton, Wordsworth, and Shakespeare. In

doing so, he then has essential and challenging questions before him: How does the poetry

of these writers work to gain such lasting and meaningful authority? What subjects

are true

to enduring poetry? What are their relative depths?—and in not too long this takes him

to investigate form as much as worthy subjects. He will, for example, come to make

some

remarkable acute critical statements about Wordsworth and Milton (some of them

comparative)—both their strengths and limitations—that then set out his unique direction.

And

then there’s Shakespeare, with his ability to be absorbed by all subjects, and Keats’s

emerging belief that he genuinely understands Shakespeare to his core—and he’s fully

serious.