11 December 1816: Meeting Percy Shelley: Joined but not Close

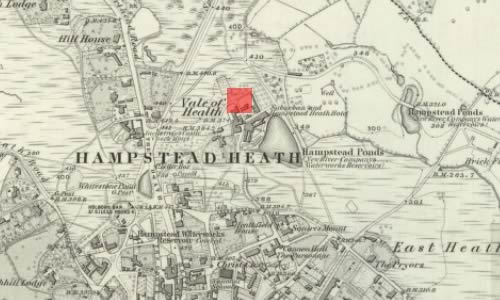

The Vale of Health, Hampstead

11 December 1816: Keats (aged twenty-one) meets the young, radical poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley (aged twenty-four) at Leigh Hunt’s cottage in the Vale of Health. Hunt has just promoted

Shelley and Keats as new Young Poets

(along with John Hamilton Reynolds) in a short essay in his paper, The Examiner. Keats is thrilled; this moment as much as any

marks his full commitment to poetry and his movement away from a medical career.

Keats never altogether warms to Shelley, though their closeness in age, general political beliefs, some common friends, and poetic aspirations might have joined the two more strongly. Reasons for their lack of a close friendship is likely based on class difference (Shelley was obviously aristocratic, and Keats despised rank), but dispositional differences also contribute to uneasy feelings, as did wildly different lifestyles and fairly divergent ideas about the role of poetry, not to mention an implicit rivalry between the two poets—who could write the most poetry, the best poetry, and longest poem, and so on. No doubt Shelley’s openly Etonian ways could be challenging.

Both poets are outsiders in different ways. Unlike Keats, Shelley is polemical, highly political, scholarly, outwardly volatile, and fervently idealistic; he is outspoken on many topics, like Christianity. It is noticeable (at least to Hunt) that Shelley likes Keats more than Keats likes Shelley. For Hunt, Shelley also represents someone from whom he might (and did) borrow money. Early on, so too would there have been some competition over Hunt’s attentions.

Four and a half years later, in the summer of 1820, things will have changed, though

neither

poet will yet have had any significant public success. Shelley hears that Keats is very ill, and in a letter of 27 July 1820, he

immediately writes a generous letter to Keats that expresses his anxieties about Keats’s

failing health: This consumption is a disease particularly fond of people who write such

good verses as you have done.

He invites Keats to Italy to stay with him in hopes of

recovery. About three weeks later, on 16 August, Keats gratefully declines, while

offering

some gentle criticism of Shelley’s poetic style and output: Keats remembers Shelley

once

advised him not to publish immature or early poetry—first-blights,

Keats calls them,

referring (quite rightly) to the overall quality of his own early work.

Keats also comments to Shelley that he wishes he could unwrite

his immature long poem,

Endymion. Keats let it be known to his friend Charles Cowden Clarke that Shelley’s Italian circle might have been a little

intimidating for him. After Keats dies in February 1821, Shelley composes a remarkable

and

classically-inspired and Miltonic elegy on Keats, Adonais, in

April (published July). The poem elevates Keats’s status while also fashioning him

as the

sensitive victim of malevolent reviewers; this sticks to Keats’s reputation well into

the

nineteenth century, though Shelley is not the first to sound the sentiment; in fact,

it is

right there on Keats’s gravestone.

Shelley drowns July 1822. Apparently Keats’s 1820 volume is in his jacket pocket, and the way it is found in the pocket suggests it was crammed in at the last moment.

Today Keats and Shelley are very much joined via the Keats-Shelley House in Rome (and its attendant Keats-Shelley Memorial Association), as well as the Keats-Shelley Association of America and its publication, The Keats-Shelley Review. The tragic, early deaths of two young, sensitive, poetic geniuses remains culturally irresistible.

[For more on Keats and Shelley, see 12 August 1820.]

.