November to December 1816: Busy & Important Months: An Expanding World yet Cloying, Aspirational Poetry

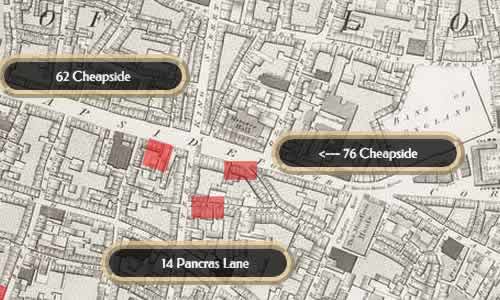

76 Cheapside, London

Where Keats lives with his brothers, Tom and George. He moves from 8 Dean Street to 76 Cheapside mid-November 1816; the stay at Dean Street is probably about one month.

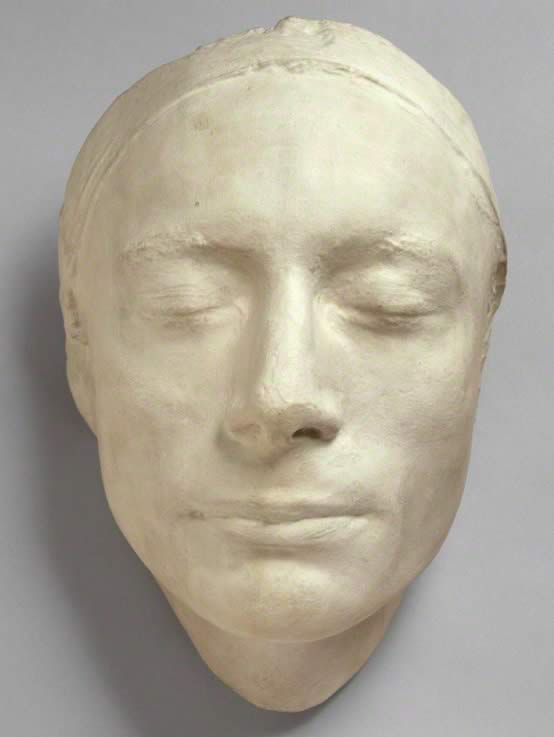

These few months are busy and formative—and crucial in reinforcing his poetic goals and direction. For example, Keats has just met established figures of London’s cultural and literary scene—including Leigh Hunt, Benjamin Robert Haydon, and John Hamilton Reynolds— as well as a fellow young poet, the outspoken, aspiring, and eccentric Percy Bysshe Shelley; he has his best poem thus far published (Chapman’s Homer) in Hunt’s The Examiner, where he is publicly noted as an important, new young poet; he meets Horace Smith; Haydon promises to send some of Keats’s poetry to Wordsworth; he has a life-mask made by Haydon;* he is certified as a apothecary; and he is very close to confirming his decision to abandon a medical career for that of a poet. [For a flowchart of Keats’s movement into the London cultural and literary scene, see Keats’s Social Network.]

Midway in this period he writes his Great Spirits sonnet. The poem

commemorates his enthusiasm for the inspirational spirit of the age, of which Wordsworth, Hunt, and Haydon are considered parts.

Within the poem’s terms, Wordsworth seems to have the highest possible standing as

a poet,

capturing his originality and high powers from nothing less than the wings of an archangel,

which may hold some allusion to Milton’s poetic prowess; Hunt’s lighter poetic character

falls

into his social smile,

but Keats recognizes Hunt’s enduring fight for freedom; as for

Haydon, Keats seems to suggest that Haydon’s artistic determination is informed by

whisperings

from Raphael, the astonishing high Renaissance painter. By late November, Haydon (always

easily flattered) communicates to Keats his enthusiasm for Keats’s poetic gifts and

aspirations. As mentioned, he has also told Keats that he plans to show Wordsworth

the sonnet;

Keats is, understandably, overwhelmed by the idea. He moves from being an almost completely

unknown poet to having his poetry personally presented to arguably the most important

poet of

the era.

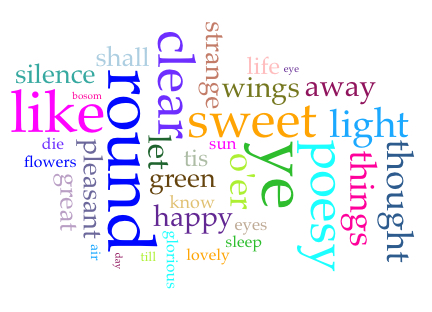

During this period, Keats also composes his thus-far most substantial verses, and

they become

the book-end poems for his 1817 collection, Poems, by John

Keats: I stood tip-toe, and Sleep and Poetry. Both poems are largely

about the desire to find inspiration and to write enduring, great poetry. Unfortunately,

neither poem is hardly successful: the language and style is often forced by the rhyme

(couplets), and the accounts of freshness, blisses, bowers, flora, fauna, birds, old

bards,

and various sweet, green pleasantries are, at once, fairly random in ordering and

predicable

in their descriptions. There is, in short, too much bowery thought and cloying desire

to be an

inspired poet. These two poems, however, do form the basis of his poetic apprenticeship

as he

searches for forms that reflect his poetic character and subjects that capture his

growing

original thinking and sensibilities. But it will take another two years of experiment

and

development to evolve that strong and original voice we know as Keatsian—unless, that

is, we

want Keatsian

to signal something between ineffectual, over-reaching, and prettified

poetry: a callow poet in search of worldly poetry.

But there is some hope in these two longer early poems, and in particular in Sleep and Poetry.

Despite the lingering jauntiness, fluttering, and sweet green delights that randomly

figure in

the poem, Keats is fully aware that he is (to use some of his own terms of reference

in the

poem) a thirsty, presumptuous novice aiming at poetic heights that are not just overwhelming

but possibly unachievable. The task, he notes, is both noble and mad. Indeed! But

for him, it

is also irresistible. This, then, is touching and endearing, but it does not in itself

add up

to what he strives for: that vast idea

(291) of exceptional poetry.

During November and December, Keats also composes a number of sonnets that will also appear in that first collection. While these are fairly stylistically accomplished and aim for larger relevance (like, for example, To Kosciusko), others express little that is outwardly poignant—like To My Brothers or On Leaving Some Friends at an Early Hour—or poetically notable. There is little original thought or striking phrasing in these poems.

More than once during this period, then, Keats pictures himself as a young poet holding

on to

his pen, quivering with poetic aspiration and anticipation. In, for example, that

latter poem

(On Leaving

Some Friends at an Early Hour, likely written early November), we have our

young poet asking for a “golden pen” and a glowing tablet; he hopes he might, while

leaning on

a pile of flowers, and by conjuring singing angels strumming the silver strings of

heavenly

harps, and while picturing pearly cars, diamond jars, pink robes, and delicious music,

be able

to “write down a line of glorious tone.” Keats’s excessive imagination, yet a sort-of

literal

grasping for something special to write with—once more, his desire to be poet—is at

once

touching and a poetic dead end. The imagery suggests that, in contending for poetic

heights,

he might on his way encounter some glittering prizes. He’ll have to wait some time,

and he’ll

have to figure out his own way to get there. (Those Friends

referred to include some

new ones, like Hunt and Reynolds.)

Keats will later acknowledge that his first collection amounts to little more than

first-blights

(letter, to Shelley, 16 August 1820), but they do provide the important

measure by which we can assess Keats’s poetic progress over the next few years.

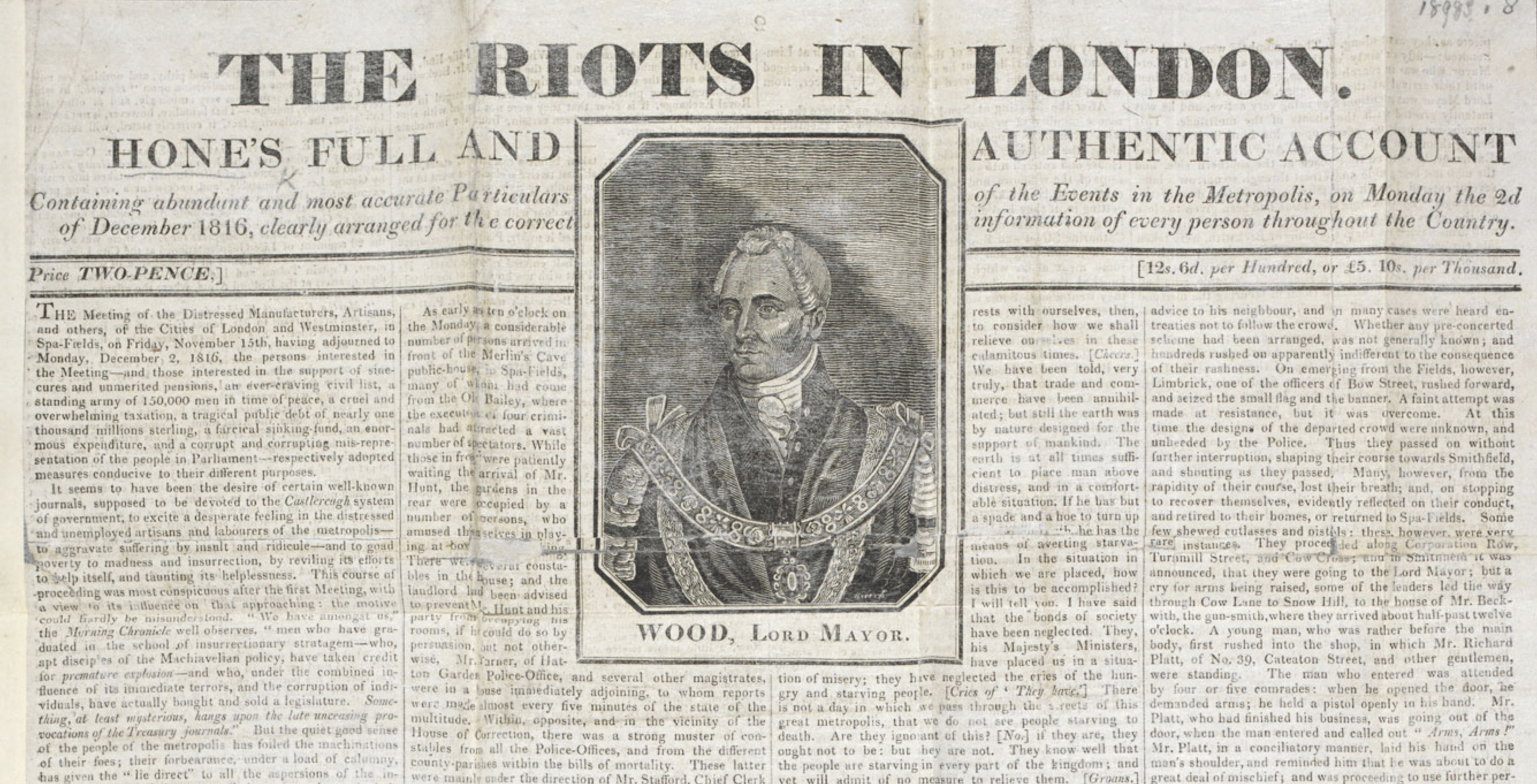

And in the background of all this activity, the last two weeks of November into early

December see fairly serious political unrest in the form political meetings in the

London area

of Islington. Initially, at least, the issue is the demand for electoral reform, as

well as to

press the government to address widespread economic distress. The organized unrest—known

as

the Spa Fields riots—that spins out from a 2 December meeting does get out of control,

with a

radical group (known as the Spenceans) attempting to storm the Tower of London and

take over

the Bank of England in order to assume power (they openly have the spirit of French

Revolution

in mind); they loot a gunsmith’s shop; gunfire is exchanged between rioters and government

forces. Habeas corpus will be suspended in March 1817. While this particular

widely-written-about event that Keats knew fully about fizzled, momentum for protest

in the

name of reform is gained, and serious incidents of unrest are set off over the coming

years.

Some of the organizers and rioters were charged with treason, but acquitted. Given

Keats’s

sympathies and company, we can tell which side Keats would have been on: as he will

write to a

friend 22 September 1819 about these public meetings

of protest, he hopes he will be

able to put a Mite of help to the Liberal side of the Question before I die.

[See 3 March 1817 for more on the publication of Keats’s first collection.]