16 March 1816: Keats, Joseph Severn, Spenser, & Chivalric Infatuations

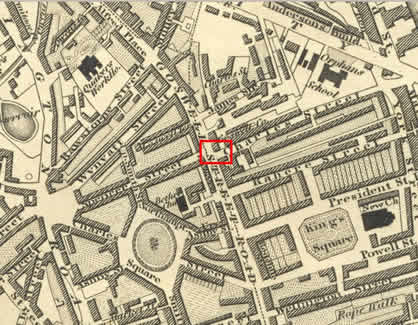

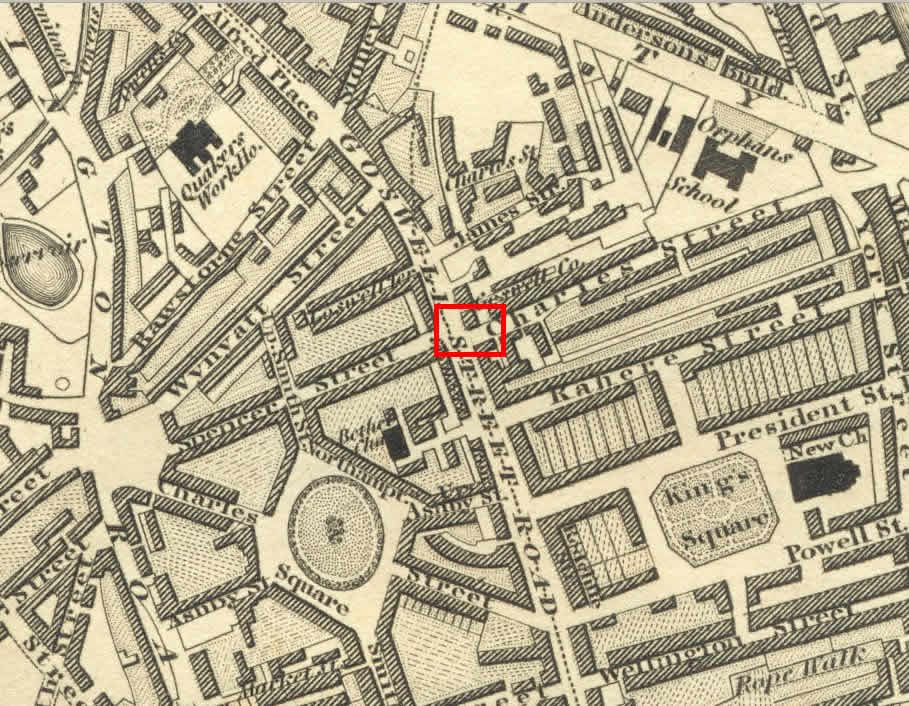

Goswell Street Road, London

Where Keats’s new acquaintance, the young painter Joseph Severn, lives. Keats likely meets the ambitious Severn in March 1816, or perhaps as early as October 1815, and likely via one of his brother George’s friends, William Haslam, who also goes on to become one of Keats’s friends and supporters.

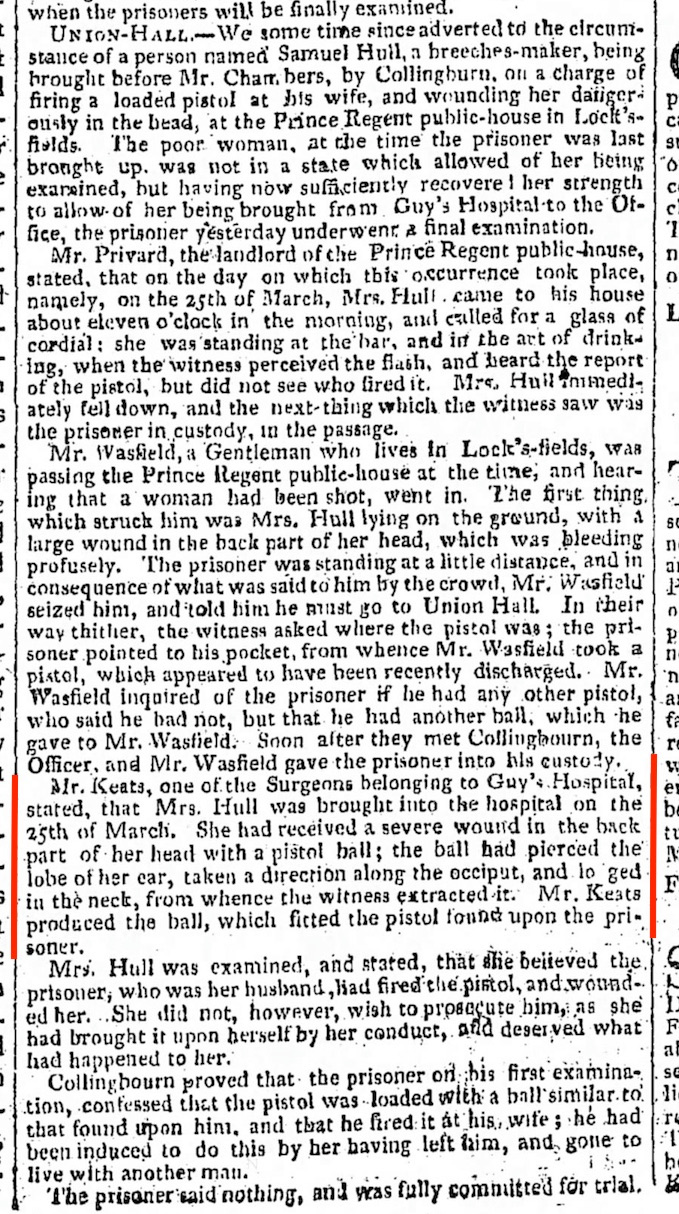

Severn is a student at the Royal Academy and about two years older than Keats. By 1817 they have become friends. At this point, Keats’s is still tied in his medical training as a surgical dresser (with fairly involved commitments), and with the presumption he will eventually become a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. How involved is Keats in his medical training and work? Well, he may have been involved enough to, on 25 March, remove a pistol ball from the back of the neck of a woman who was shot by her possessive husband.*

Mr. Keatsremoves a pistol ball, in The Morning Chronicle, 23 April 1816*

Importantly, Severn talks with Keats about art, and they visit museums together. Severn also sketches Keats in December 1816, and he paints a miniature of Keats in 1818 (exhibited at the Royal Academy in May 1819, though against Keats’s wishes).

Why is this connection with Severn important? Keats will become critically absorbed by how art, in its evocative, eternal, and mysterious silence, represents elements like beauty, movement, and feeling; the work of the artist is seen, but not the artist. This absorption will eventually propel Keats’s poetic progress while also becoming a subject in his poetry—manifest, for example, in a fading nightingale, a lingering season, a pale knight, and a classical urn. But this is to come.

But at this point in his writing, in early 1816, Keats is still somewhat wrapped up in portraying chivalric motifs, moments, and imagery, prompted mainly by Edmund Spenser’s work. Generally, Spencer’s work is pointed to as initiating Keats’s poetic aspirations. Certainly the luxuriousness and sensual nature of some of Spencer’s work sticks with Keats, almost to the very end of his writing career. But at a deeper level that Keats will also eventually have to address, he, like Spencer, will have to grapple with the division between the real and the ideal. In 1816, Keats is not there yet.

The best examples of Keats’s early Spenserian

enthusiasms and sentiments appear in his poems Specimen of an Induction to a

Poem and Calidore: A Fragment. The former poem (which also flatteringly nods to the

poetic influence of Leigh Hunt’s The Story of Rimini) repeats the self-directed imperative to

tell a tale of chivalry

with all the accompanying tropes; the latter poem actually

applies these predictable tropes, and so of course we encounter a tall, elegant, and

gloriously armored knight, patting the flowing hair / Of his proud horse’s mane

(110ff.). These are not good poems, but they supply a measure how far Keats will have

to come

in order to drop clichés, poetic infatuations, derivative sentiments, and unoriginal

style.

But then again, he is only 20 years old. The title of the earliest poem we have by

Keats

reflects his initial significant influence and early poetic aspirations: Imitation of

Spenser, likely written in 1814. Despite the poem’s gushing mossiness, lawniness,

and flowery-bowery description—including, of course, fleecy white

clouds—Keats thought

enough of the poem to include in his first collection, the 1817 Poems,

by John Keats.

When Keats dies in Rome in February 1821, Severn is with him. He is utterly devoted to Keats in those final, agonizing months. Severn’s often sad, stressed, and graphic descriptions of Keats (and in a few sketches) are all we have to understand what Keats goes through in the final months of his life as he wastes away from consumption. Severn is largely responsible for seeing to Keats’s burial in Rome. Severn will openly attempt to benefit from Keats’s growing reputation into the nineteenth century, and (by his own wishes) he is buried beside Keats.

For more about Severn and Keats in Rome, see 13-16 September 1820 and 21 October 1820.

* The woman does not die. She does not charge her husband. The incident is described

23 April

1816 in the Morning Chronicle (above) and mentions a Mr. Keats of Guy’s as one of the

surgeons. That Keats is the surgeon in question is stated by Nicholas Roe in Mr. Keats,

in Essays in Criticism, 65:3 (July 2015): 274-88. There is a

chance, however, that there may have been another Mr. Keats

on the scene: a certain

Mr. Keats, a surgeon,

is mentioned in The Times for 22 June 1821 and The

Examiner for 24 June 1821 as working on wounds; our Johnny Keats is of course dead by

this time. Are the 1821 mentionings misprints? Do they mean the well known surgeon,

Dr. Robert

Keate? Or perhaps the Mr. Keats mentioned in 1816 is not our poet.