21 October 1820: This Kind of Suffering

; Arrival in Naples, Not in the World, &

An Intellect in Splints

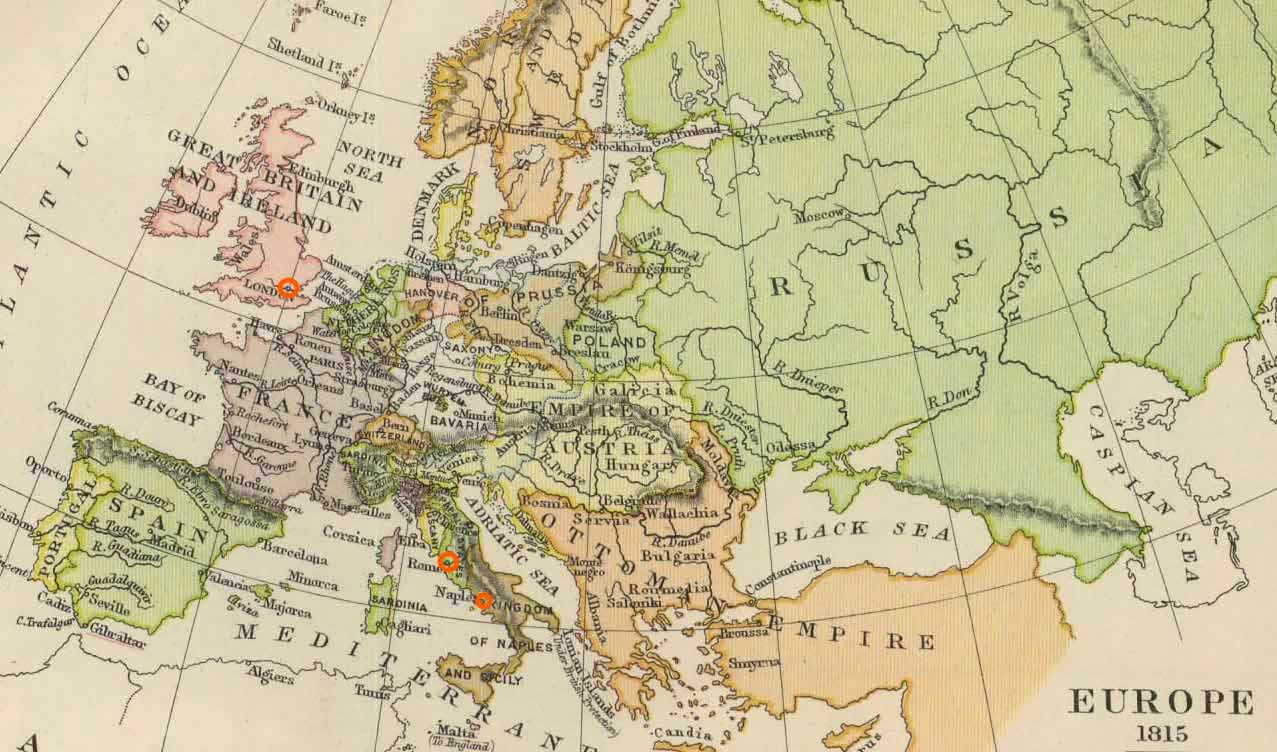

From London to Naples to Rome

On 17 September, at the London Docks and with his friend, the young painter Joseph Severn, Keats steps on board the brigantine rig Maria Crowther (a boat designed for cargo, not passengers). A few other friends—Richard Woodhouse, John Taylor, and William Haslam—will travel as far as Gravesend with Keats and Severn.

Keats is to voyage to Italy, with waning hopes to restore his sinking health. There

is little

doubt he is consumptive—the so-called wasting disease or white plague—and what we

call

pulmonary tuberculosis. Blood-letting and restrictive diets will end up making his

condition

worse, as do remedies ranging from laudanum to mercury. That the diagnosis he gets

points to

emotional or mental issues as the causes of his condition (including agitation caused

by

thinking about poetry) is also unfortunate; Keats himself often refers to his sometimes

uneven

emotional state (that can be boiled down to nervous anxiety and occasional depression)

as the

cause of his difficulties; but all of this clouds the hard truth of the moment: he

is dying

from TB. On the last day of September, he surveys his condition, and, in his sadness

crossed

over with hopelessness, he turns a little philosophical: we cannot be created for this kind

of suffering

(letter, 30 Sept 1820).

There are a few others on board with Keats, most notably, perhaps, a certain Miss

Maria

Cotterwell, who, like Keats, suffers in the last stages of consumption. Her frail

presence, in

Keats’s own words,vexed

and preyed upon

him—no doubt they do, since he sees in

her fevered face his own fate reflected, in all her bad symptoms

(22 or 24 Oct). She

will die just a few months after Keats, aged twenty.

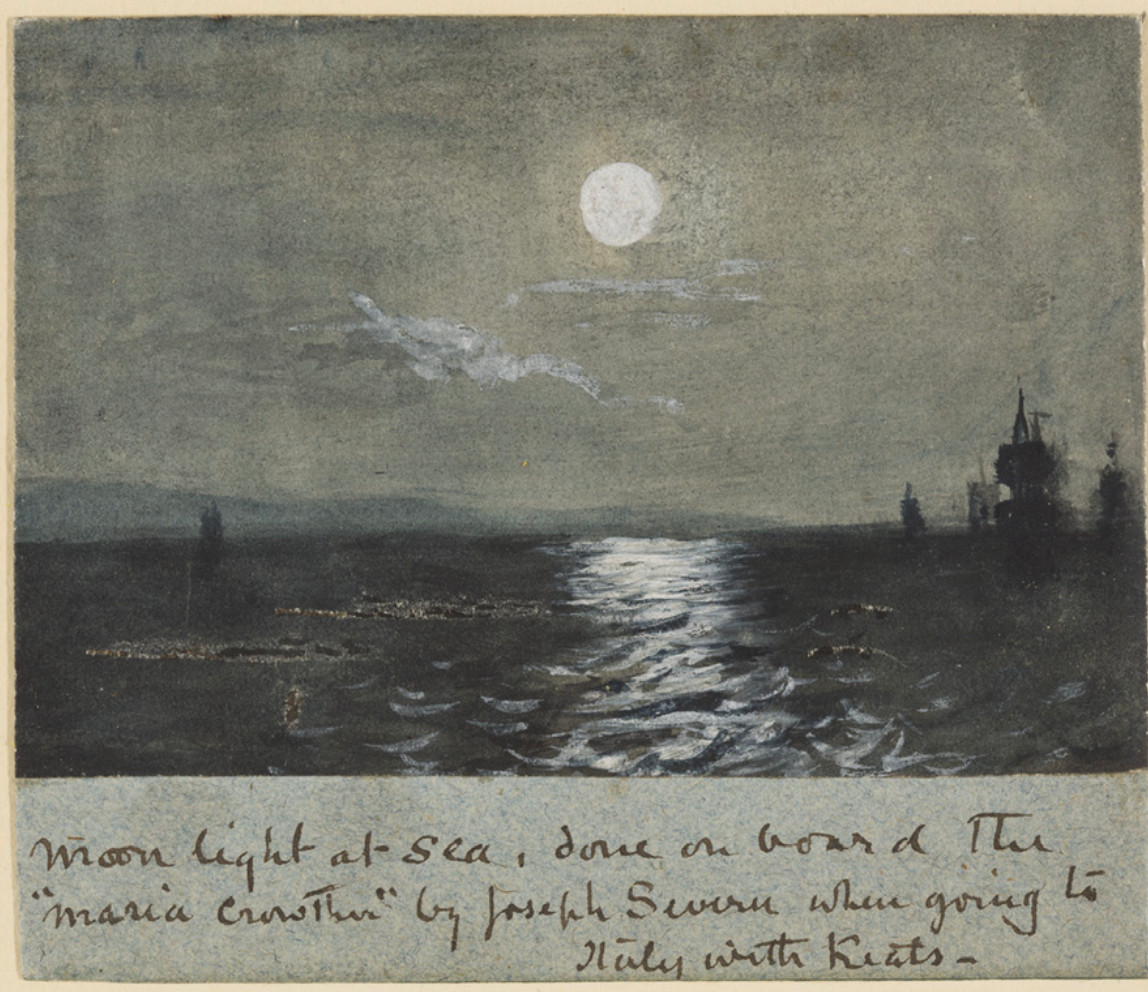

done on board the Maria Crowther.Image courtesy of Keats House, City of London Corporation (K/PZ/02/001). Click to enlarge.

On 21 October, thirty-five days after boarding, and after a very rough voyage, Keats arrives in Naples, only to have the cramped vessel quarantined for ten further days over fears of typhus originating in London. Conditions on board during the quarantine are terrible, especially after a voyage with such constricted quarters. He cannot even rouse himself to write about the beauties of the Bay of Naples, though while in Naples he is taken to see an opera, in hopes of reviving at least something of his failing spirit.

On 31 October, the day of his 25th birthday, Keats finally sets foot on shore. From

Naples,

thinking about his disarranged love for Fanny

Brawne completely overwhelms him, and he attempts, though he cannot, to avoid

thoughts of what might have been. His feelings, he writes, are coals of fire,

and

conjuring one of Wordsworth’s major tropes

while questioning his fate, in a letter of 1 November to his closest friend, Charles Brown, he writes, It surprised me that the

human heart is capable of containing and bearing so much misery. Was I born for this

end?

This in fact captures an important point in Keats’s poetic thematics. What is the

deep meaning of human suffering and sorrow? And this, then, also takes us back to

Keats’s

profound philosophical exploration of what it is to see into the heart of man, which,

in May 1818, takes Keats to consider human life via the simile of

entering a Mansion of Many Apartments,

where, if we go deep enough into the many

chambers of that mansion—into human life—the sharpening of one’s vision reveals that

the

World is full of Misery and Heartbreak, Pain, Sickness and oppression.

Keats is now, in

effect, in October 1820, not just seeing far, far into that Mansion—he is, as it were,

living

within its darkened passages. Keats writes that to even see Fanny’s name written would

be

more than I can bear,

and according to Severn’s later recollections, at this time

Keats could not let go of a gemstone that Fanny gave him—an oval white carnelian.

After getting a visa, Keats sets off for Rome from Naples a week later. Severn seems to have picked some wild flowers to accompany them on the journey. Keats arrives in Rome 15 November, with a short-lived reprieve from the illness.

Keats is in poor condition; chances for recovery are impossibly slim. He will receive well-intended medical attention from a physician, Dr. James Clark, including blood-letting and eating restrictions. Keats is fevered, in pain, and has been spitting up blood; he is more or less confined to his bed and to the small quarters; Severn feels equally trapped. Symptoms that are earlier centered in his lungs seem now to have spread to his stomach (he complains of indigestion), which, given that pulmonary tuberculosis can cause bleeding in the intestines, is not surprising. The illness may have lingered and progressed slowly for as much as two years. Keats fully witnessed the deaths of both his mother and his youngest brother, Tom, to the illness.

Keats, then, knows what is coming. And so, even while he was in quarantine in Naples,

his

thoughts are of the inevitable—in a way, he feels his life is already over: to Mrs. Brawne, the mother of his love, Fanny, he writes, I do not feel in the

world

(22 or 24 Oct). In the same letter, he wishes he could give an account of the Bay

of Naples; he repeats his feeling of being separated from this life; his forlorn wish

is to

once more be a Citizen of this world—[. . .] O what a misery it is to have an intellect in

splints!