13-16 September 1820: To Italy: Beyond Every Thing Horrible & a Sense of Darkness

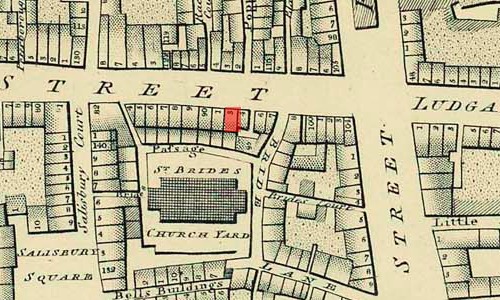

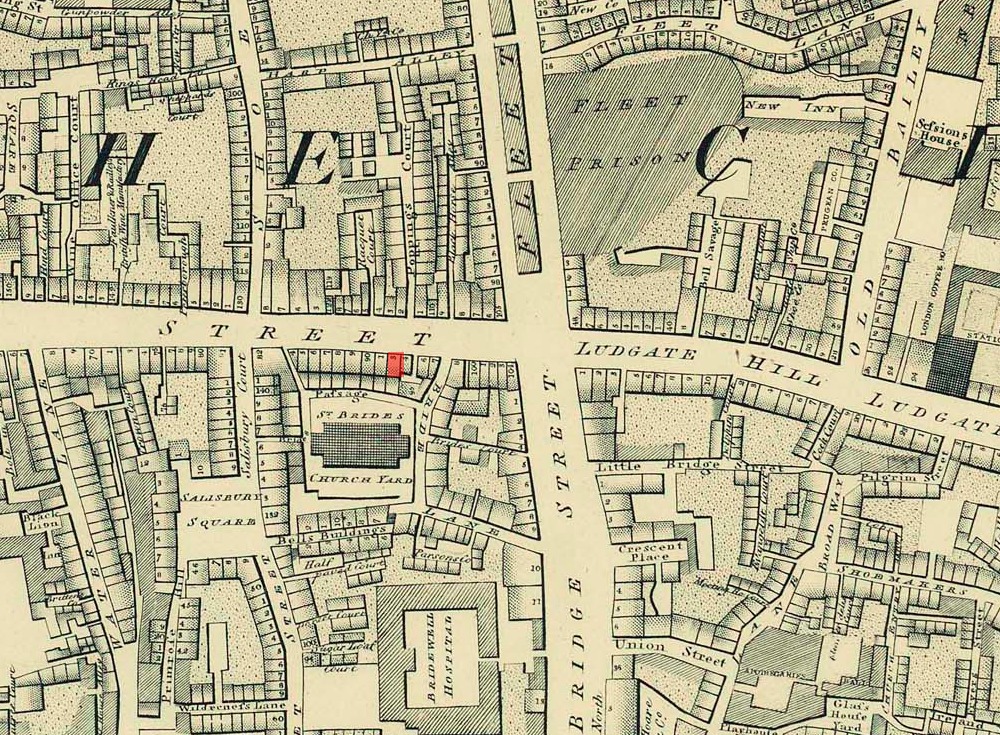

93 Fleet Street, London

93 Fleet Street, London: the offices of [John] Taylor & [James Augustus] Hessey, publishers of Keats’s last two volumes of poetry (May 1818 and July 1820), and owners to the rights of his first 1817 collection, Poems: Where Keats between 13-16 September stays as he prepares to depart for Italy in an effort to restore his fading health.

Keats assigns (sells) copyright of the three volumes to Taylor & Hessey on 16 September, which provides some money for the cash-strapped Keats—money he needs to get to and stay in Italy. Taylor finds him passage to Italy on the brigantine rig (twin-masted) Maria Crowther, a boat suited for trade and not passengers (technically, 127 tons register). Taylor will also place some additional funds in a bank in Rome for Keats to use, ostensibly to cover payment for future publications by Keats. The trustee of the Keats family finances, Richard Abbey, coldly resists releasing any funds (or loaning any) to Keats to help with the trip. Keats is twenty-four years old.

For about two years Keats has shown lingering signs of illness, initially centered

in chronic

throat problems; but over the last eight or so months, the problem shifts to his chest

and

lungs and manifests in blood-spitting—hemoptysis. On 23 August, he refers to it as

the

oppression I have at the Chest.

He has a return of hemorrhaging late August. This all

points to consumption, something Keats is well aware of, especially given his family

history

(Keats witnesses his youngest brother and

mother die of tuberculosis). Keats writes

what will be his last known letter to his sister, Fanny, that the trip is in hope of re-establishing my health

(11 Sept), but

for the sake of his younger sister, Keats softens the more realistic and darkened

prognosis.

Keats actually dictates the letter to Fanny

Brawne, his betrothed.

While Keats’s very close friend Charles Brown (Keats’s former roommate, travelling companion, and financial supporter) is the best choice to accompany Keats to Italy, another of Keats’s friends, the young painter Joseph Severn (aged twenty-six) generously agrees to accompany Keats, since Brown is up in Scotland, and not so easy to contact. Brown, though, when he does find out about Keats’s plans, travels hastily to London in the belief he will accompany Keats, but Brown just fails to connect with Keats. Their respective ships, in fact, will be moored close to each other (just off Gravesend), and going in opposite directions; they had no idea.

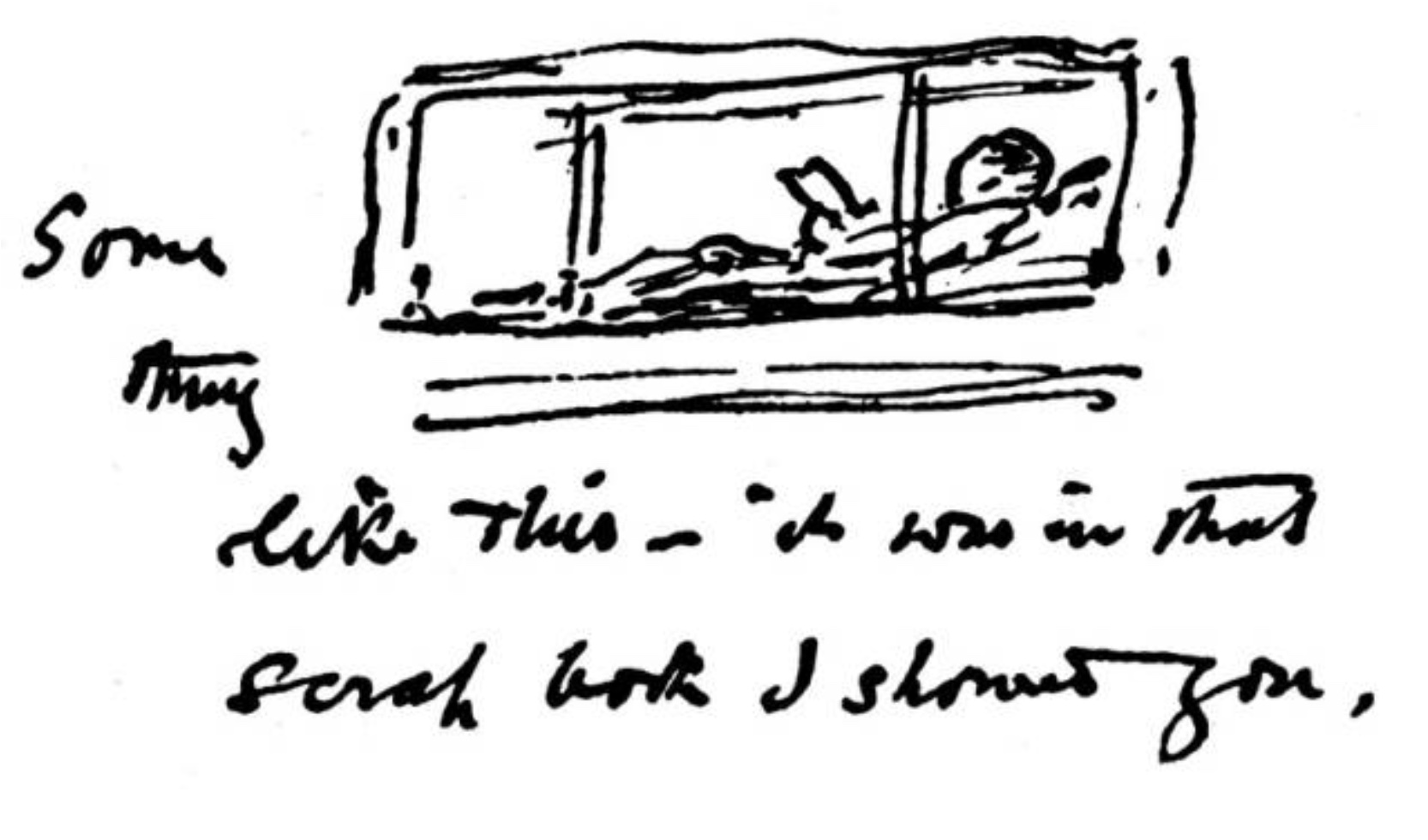

At the London Docks, Keats boards the two-masted, 130-ton brig Maria Crowther, on the morning of 17 September, and he is introduced to his dark and fairly cramped quarters (the vessel, built 1810, was intended for cargo, not passengers; the ship ran around in 1837 and was wrecked). Keats’s will share the ship’s cabin with Severn, two other passengers (including another consumptive), and the ship’s captain, Thomas Walsh. A few friends sail with him as far as Gravesend, from where he departs on 18 September. Severn initially reports that Keats’s spirits are temporarily improved and his humor waggish, but this may have been Keats attempting to put on a good face in spite of the odds. A two-day storm, however, makes progress impossible. The 24th is spent on shore at Portsmouth. By about 2 October the ship finally clears the English Channel.

The Maria Crowther, Sailing Brig,by Joseph Severn, 1820. Water colour. Image courtesy of Keats House, City of London Corporation (K/PZ/02/002). Click to enlarge.

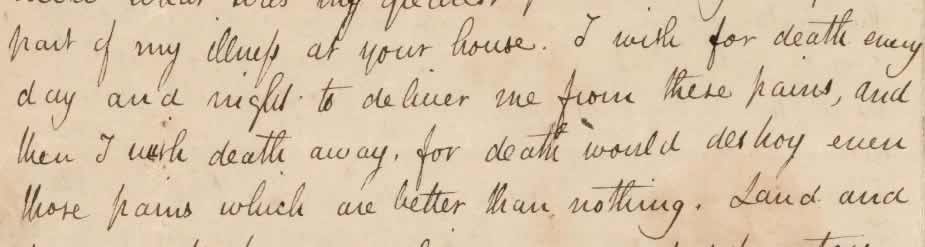

On 30 September, Keats writes to Brown, and

his feelings about death surface in the context of his regard for his betrothed, Fanny Brawne. Death is a deliverer from suffering, he

notes; yet it is the great divorcer

from what he loves—Fanny, whom he fears he will

never again see. He writes, The thought of leaving Miss Brawne is beyond every thing

horrible—the sense of darkness coming over me—I eternally see her figure eternally

vanishing.

Before leaving Fanny, the two exchange gifts, including a miniature painting

of himself done by Severn; Fanny takes a lock of

his hair, they exchange rings, and she gives him a semiprecious oval stone (white

carnelian)

to hold in order to remind him of touching her, as well as a silk lining for his cap

that

tortures his imagination. Keats also has a couple of trunks, which, besides letters

from

personal friends and his brothers, and a warm coat, contain two editions of Shakespeare’s plays and the first cantos of Lord Byron’s Don Juan

(published July 1819). Keats also takes letters from Fanny Brawne, and these will

be buried

with him—unopened.

Keats arrives in Naples on 21 October, making it a 35-day stormy voyage, though on arrival he is quarantined ten further days. Keats, who has his 25th birthday probably on the day he is out of quarantine, reaches Rome by carriage 15 November. He will pass away in Rome, 23 February 1821, at 26 Piazza di Spagna.

Severn remains with Keats throughout these difficult months. After Keats’s passing, he spends the next two decades in Italy before returning to England. Upon Keats’s death, Severn almost immediately champions Keats’s cause, though in some ways he is motivated by a desire to better himself by attaching himself to Keats’s rising status. Others, too, will want to associate themselves with Keats’s growing reputation into the mid-nineteenth century. To support the posthumous Keats became, for some, not just the self-serving mantle of seeming to stand up for someone who martyred himself to art, but to signal, in effect, I have known genius.

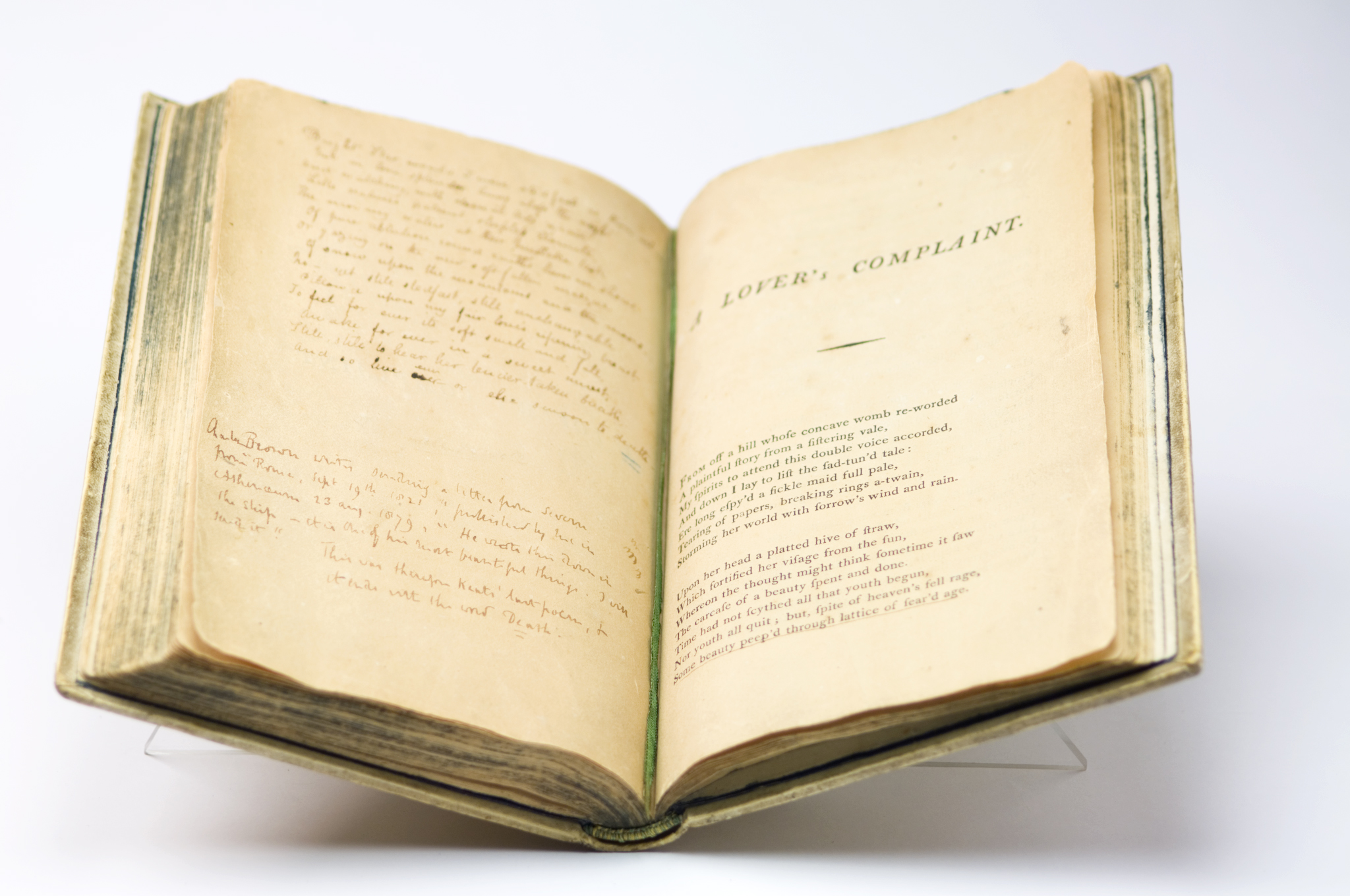

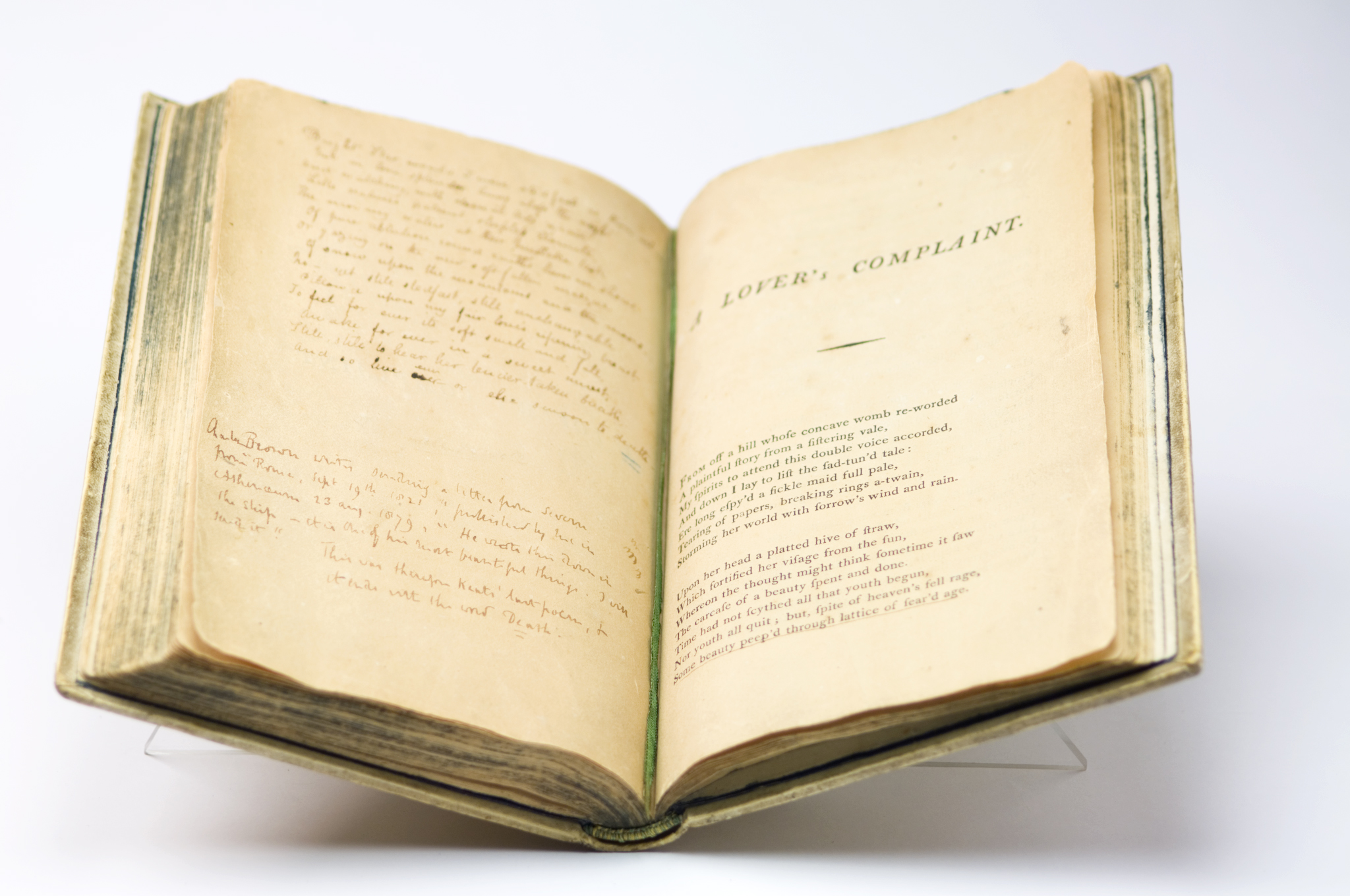

Bright Starin his copy of Shakespeare’s Poetical Works, on a page across from A Lover’s Complaint. Image courtesy of Keats House, City of London Corporation (K/BK/01/010). Click to enlarge.