26 February 1821: Writ on Water

: Keats’s Burial, After-fame, & Indeed, Among the

English Poets

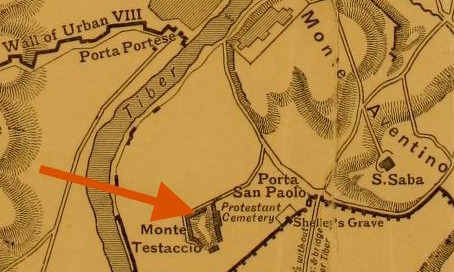

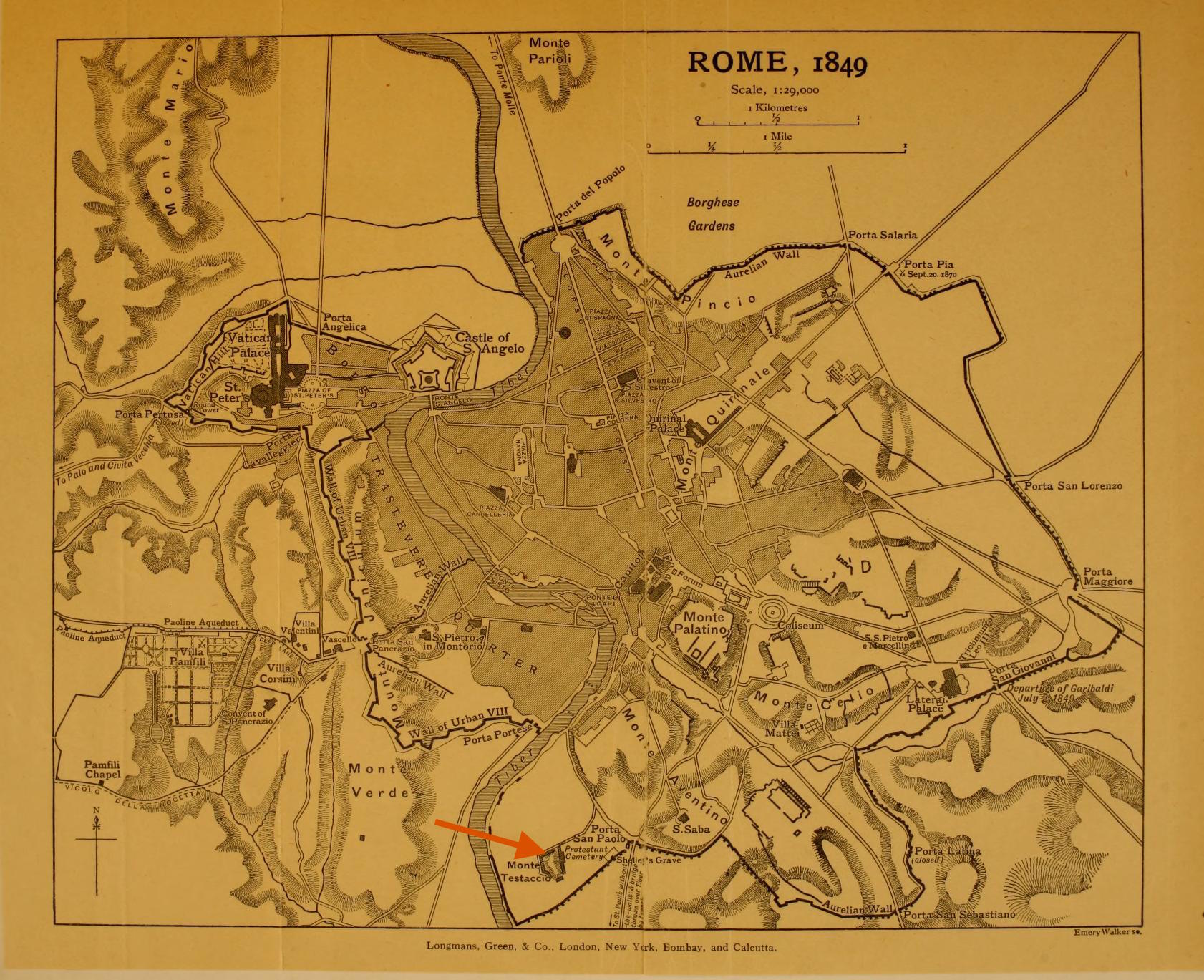

The Non-Catholic (Protestant) Cemetery, Testaccio, Rome

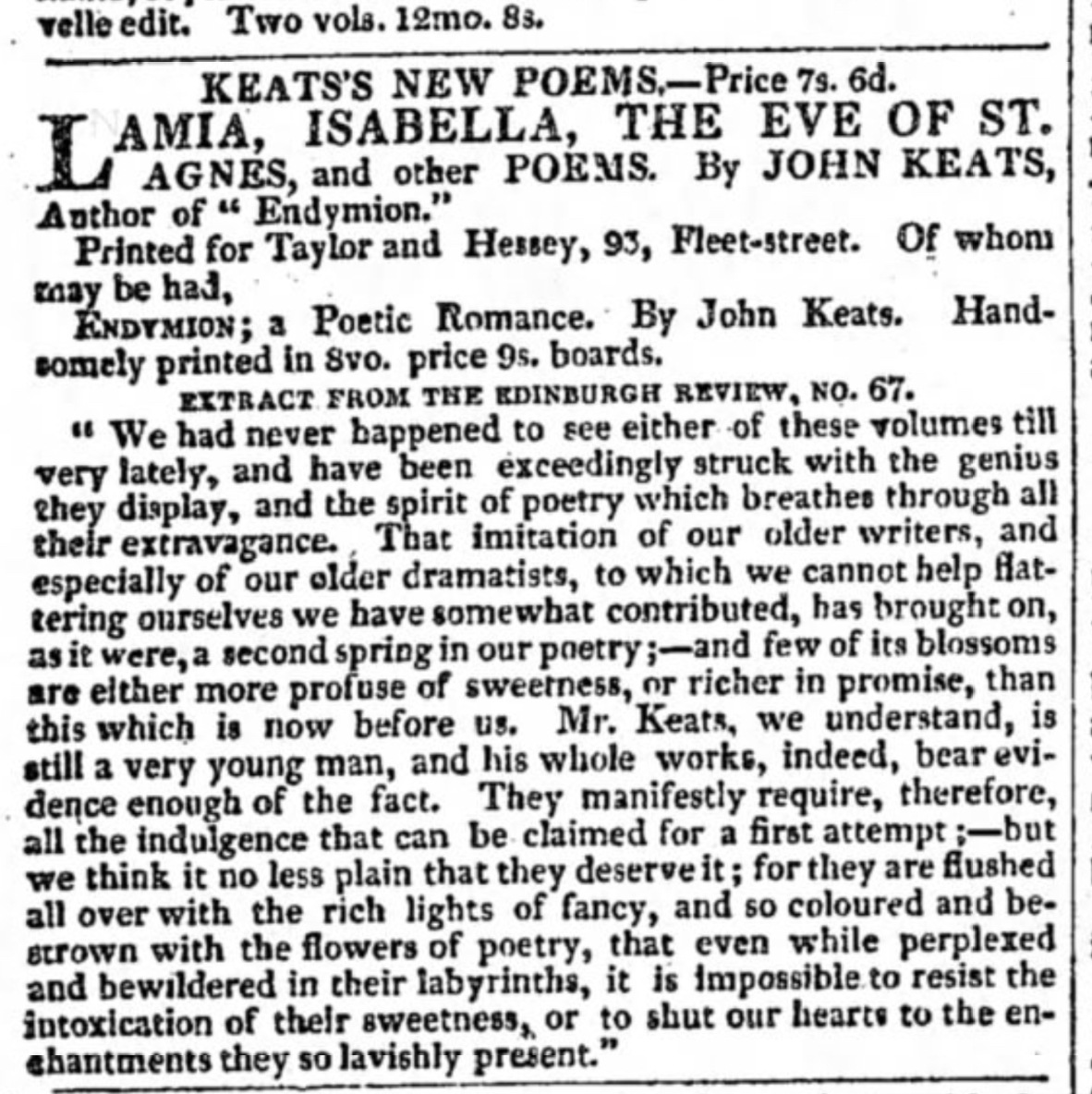

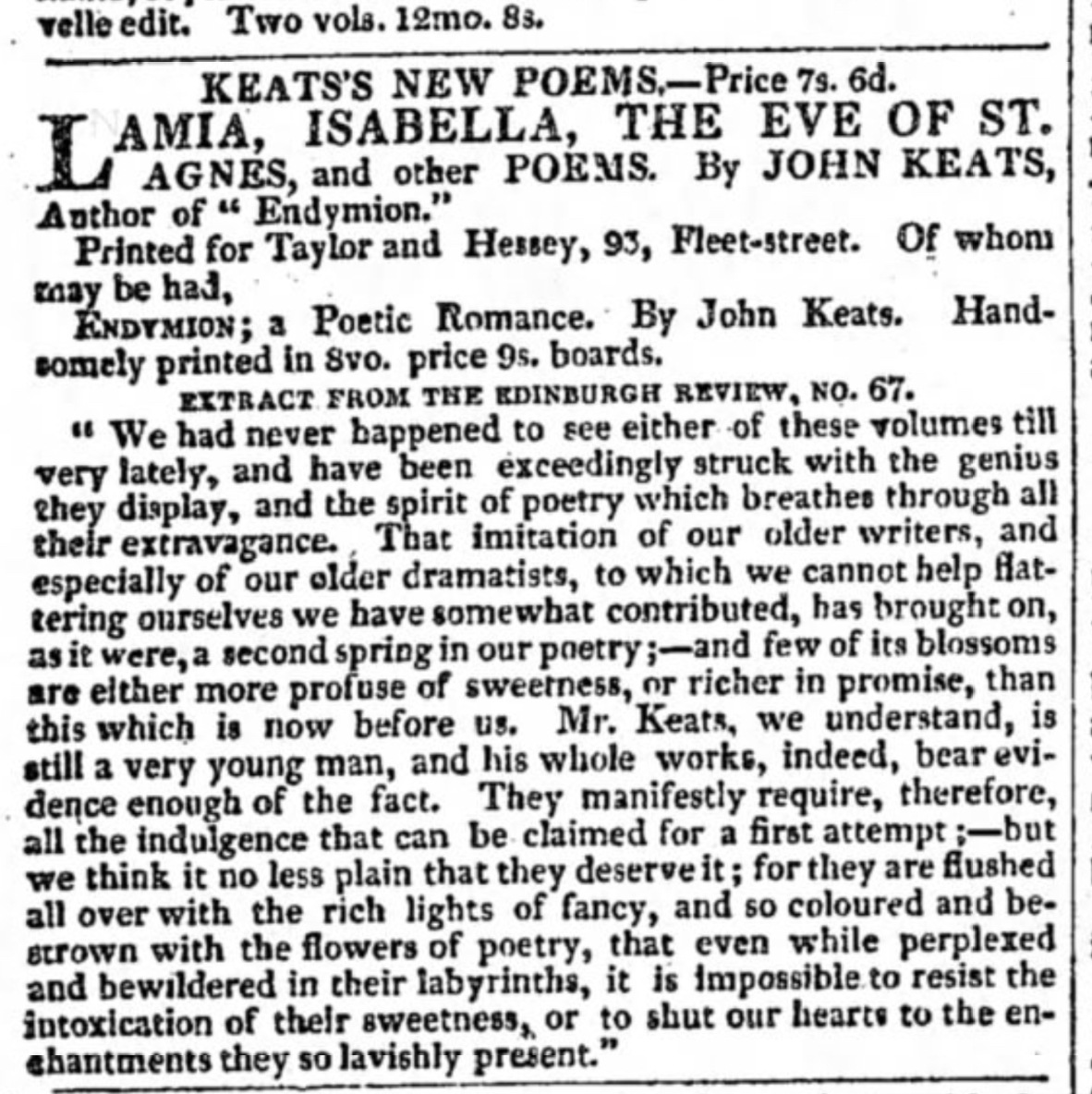

Three days after passing away, on the morning of 26 February 1821, at about 9:00 am, Keats, aged twenty-five, is buried in the Protestant Cemetery in Rome (also known as the Non-Catholic Cemetery or English Cemetery), in the specific area known as the Old Cemetary in the English burial-ground. The placement of the grave begins a new row. He has been in Rome since 15 November 1820, staying at 26 Piazza di Spagna (now Keats-Shelley House, a museum). Three days after his burial, back in London, his remarkable final volume of poems is being advertised, unaware of Keats’s passing.

Keats’s New Poems,advertised in The Morning Chronicle, 28 Feb 1821, unaware of Keats’s death

Keats has for months suffered horribly in the final stages of the agonizing illness

of

consumption—pulmonary tuberculosis, the so-called wasting disease

—before he dies the

evening of Friday, 23 February, likely sometime shortly before midnight. The person

with Keats

at the time, the young painter Joseph Severn,

reports that Keats’s last fight against death begins at 4:30 in the afternoon and

lasts for

seven hours. Severn reports hearing the phlegm boiling

in Keats’s throat before he

slowly sinks into death. Severn reports Keats saying, I shall die easy—dont be

frightened—thank God it has come.

[For much more on Keats and consumption, see 3 February 1820.]

Severn has, without relief, since mid-September 1820, watched over Keats, which is when they begin their voyage to Italy from London in the vain hope of reviving Keats’s health. But the course of the highly contagious illness—which previously kills both Keats’s younger brother, Tom, and earlier his mother—is set. That Keats had experienced a chronic sore throat since late summer 1818, just as he returns completely exhausted from a grueling northern tour in September of that year, only to begin nursing Tom to his death 1 December 1818, suggests Keats may have been infected for much more than a year. Tom himself showed signs of consumption as far back as summer 1816, and that he dies from it more than two years later might also point to an even earlier date for Keats’s contraction of the illness. Severn, besides being completely emotionally and physically depleted, at moments sounds like he has been traumatized by the ordeal of hopeless care; now negotiating practical and financial issues adds to his extreme distress. Law demands that everything in Keats’s rooms, including walls and floors, be destroyed.

Plaster casts of Keats’s hand, foot, and face are made the day after he dies. The

death mask

subtly reveals a thinned, pained face, with some of his features pronounced because

of his

emaciated state. About two weeks after Keats dies, in a letter dated 6 March, Severn reports back to Keats’s good friend and

publisher, John Taylor, that the autopsy revealed

the worst possible Consumption—the lungs were entirely destroyed—the cells were quite

gone.

Keats had been told that where he was to be buried is overgrown with flowers, and

he is

apparently comforted by the idea. Severn reports

Keats saying, I shall soon be laid in the quiet grave—thank God for the quiet grave—O! I

can feel the cold earth upon me—the daisies growing over me—O for this quiet—it will

be my

first.

Keats’s words suggest, too, that he has been unsettled—emotionally? physically?

both?—for some time. But we have to keep in mind, first, that Keats is on his deathbed,

and

what he says needs to be tempered by such a difficult, agonizing moment of directly

facing the

end of his life; and second, this is Severn (himself emotionally strained) reporting,

so the

veracity of Keats’s exact words needs considerations. In early May, Severn reports

that

daisies have grown over the grave; he writes to another of Keats’s good friends, William Haslam, that it is a romantic

spot.

Keats is buried with a couple of unopened letters from Fanny Brawne, which, while he was alive, he could not bear to read for the pain they

might bring. A few month before he passes, Keats agonizes, O that I could be buried near

where she lives!

(1 Nov 1820). Turfs of daisies are placed around and on the grave.

Severn will be buried beside Keats in 1882,

and, upon his wishes, the two graves are fashioned identically.

By about the third week of March, the first public announcements of Keats’s death are made in London; and then many obituaries (perhaps numbering over fifty, and published throughout Britain) immediately set Keats’s reputation rolling.

Keats desired that his epitaph have the following—and no more: Here lies one whose name

was writ on water.

The line is obviously poetic, and it expresses Keats’s perception of

his own status as a poet. But, more subtly, the line enacts Keats’s inspired theory

of the

poetical Character,

that the poet and his subject become as one, that the

camelion,

empathetic poet disappears into and blends with his subject. As Keats

writes in anticipation of his greatest work, A Poet [ . . . ] has no Identity—he is

continually in for—and filling some other Body—The Sun, the Moon, the Sea . . .

(27 Oct

1818). In his epitaph, Keats hopes that who he is, his Identity,

be dispersed into

water. In short, Keats, with such a negatively capable phrase, is, until the end,

a poet

consistent with his poetics.

Perhaps, then, Keats would have preferred his initial grave, since it had nothing on it; the final version with the full gravestone (just over a yard in height) does not appear until about late May 1823. The gravestone is the work of Severn along with Joseph Gott, who at the time shares accommodation with Severn in Rome, and who had won a Gold Medal in sculpture at the Royal Academy. The sculpture on the top portion of the gravestone depicts a classical Greek lyre with half its strings missing, suggesting, of course, lost poetic potential—a song, as it were, only half finished, and a life, alas, only half completed.

Unfortunately, Severn and Charles Brown dismiss Keats’s wish and add their own sentiments to

the tombstone (there is also a missing quotation mark; there’s not enough space to

squeeze it

in, it seems). In doing so, they promote Keats as the sensitive, resentful victim

of

vindictive powers, when in fact Keats openly accepted that his early work was immature,

deficient, and regrettable; that is, he saw his early efforts as the unfortunate though

necessary steppingstones toward poetic maturity. Keats also understood that the most

malicious

reactions were largely politically motivated, since association with Leigh Hunt’s circle (and the so-called Cockney School

) as

well as his inexperience, immediately makes him a easy target. In truth, the vast

majority of

reviews of Keats’s work while he was alive were neutral or positive, though the negative

ones

were the most forceful and animated, and often critically correct in pointing out

particular

flaws in his earlier work. Often enough (and correctly), positive, neutral, and negative

criticism points to the influence of Hunt’s poetic style and sentiments.

The epitaph:

This Grave

contains all that was Mortal,

of a

YOUNG ENGLISH POET,

Who,

on his Death Bed,

in the Bitterness of his Heart,

at the Malicious Power of his Enemies,

Desired

these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone

“Here lies One

Whose Name was writ in Water.

Feb 24th 1821

The apparent error in dating—Feb 24th

rather than the 23rd—is not made by Severn or

the stonecutter, but probably based on when, in Roman practice of the time, a new

day begins:

with Ava Maria

being sung in the church at sunset; and, as mentioned, because Keats

dies later in the evening, this places his death the next day. (My thanks to Nicholas

Stanley-Price for recalling this point of dating Keats’s death; see, too, the Summer

2012

issue of the Newsletter of the Friends of the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome.)

The first full biography of Keats (by Richard Monckton Milnes—later Lord Houghton) will not be published until 1848. But immediately after his death, Keats’s friends and their circles begin to promote his cause and, more interestingly (and with some in-fighting, possessiveness, and myth-making), shape his image and nurture connection with the fallen poet. For example, Severn will himself go on to socially, and then culturally, profit by his association with Keats—and very intentionally so; as mentioned, he made sure that his grave was beside Keats’s; and post-mortem, Severn’s son (Walter) and others in Rome ensured that the graves were more or less identical and complementary, with connecting motifs on their respective tombstones.

Initially, then, Keats’s after-fame often enough revolves around the problem of how to represent Keats himself, rather than on a critical engagement with the unique and persistent quality of his best work. As the century moves forward, Keats comes to perhaps haunt Victorian culture (and Pre-Raphaelite enthusiasms in particular) more than any other poet. Thus we get a number of inconsistent, overlapping, and even contradictory constructions of Keats through the nineteenth century, some of which spill over into the twentieth. If we pull apart and shuffle those emergent images of Keats, we might come up with the following versions, character entanglements, and disparate critical assessments:

- Keats: the undeserving victim of critical abuse from certain cruel, disparaging quarters of Britain’s partisan review culture; not much more that an apothecary poet;

- Keats: forever confined not just as member of Leigh Hunt’s Cockney School of Poetry, but the Cockney School of Politics; a political poet representing London’s liberal-left culture and intelligentsia in conflict with the conservative establishment; the sensible account: Keats as a target of party politics;

- Keats: a manly young man, loved and respected by his equally manly friends—strong, virile, resolute, and without an ounce of malice;

- Keats: the stroppy London lad—an upstart—determined to make a name for himself, with imaginative gifts that allow him to rise above and then transcend social constraints and impoverished circumstances;

- Keats: the vulnerable, sensitive, delicate, untutored—and sensual—genius, cruelly struck down by an age that never understood him, suffering his fate to the very end;

- Keats: the very image (embodiment, figure) of unrealized promise and poetic potential;

- Keats: a poet of youthful potential only—an eternal, boyish adolescent, who never matured beyond some immature and unprincipled morals and unbridled, affected verses;

- Keats: the languishing, ethereal aesthete, with himself the object of art, beauty, and truth; more the artist than the thinker;

- Keats: the producer of mere ornamental, decorative, ineffectual verse;

- Keats: the sensuous, passive genius of undecided sexuality; a producer of effeminate and unmanly poetry, and at best crude or vulgar;

- Keats: the weak, flawed writer of pathetic love letters to Fanny Brawne (this image emerges after the publication of these

letters in 1878, which causes a minor literary scandal; Paul de Man in 1966 will call

the

letters

unbridled erotic despair

); - Keats, according to Matthew Arnold, in 1880: the son of someone who worked

in the employment of a livery-stable keeper,

with the fevered, fragiletemperament of a consumptive

; a poetenchantingly sensuous,

sometimes unconstrained in his feelings and expression; in the unfortunate letters to Fanny Brawne, an ignoble, underbred, and unconstrained youth; lacking inthe faculty of moral interpretation,

yet also a man of strengthening virtue and very strong character, of true self-judgment and remarkableclear-sightedness,

addicted to great poetry, and lucidly possessingintellectual and spiritual passion

; in his best poetry: equal with Shakespeare in hisperfection of loveliness

(fromIntroduction to Keats

); - and then, to move just out of the Victorian era and into the early twentieth century:

the

picture William Butler Yeats (ever dichotomizing to suit his own narrowed poetic identity

and modernist purposes) gleans from some of the above: Keats as the

poor, ailing and ignorant

schoolboy, his face and nose pressed up against the candy-shop,the coarse-bred son of a livery stable-keeper

(fromEgo Dominus Tuus,

1919).

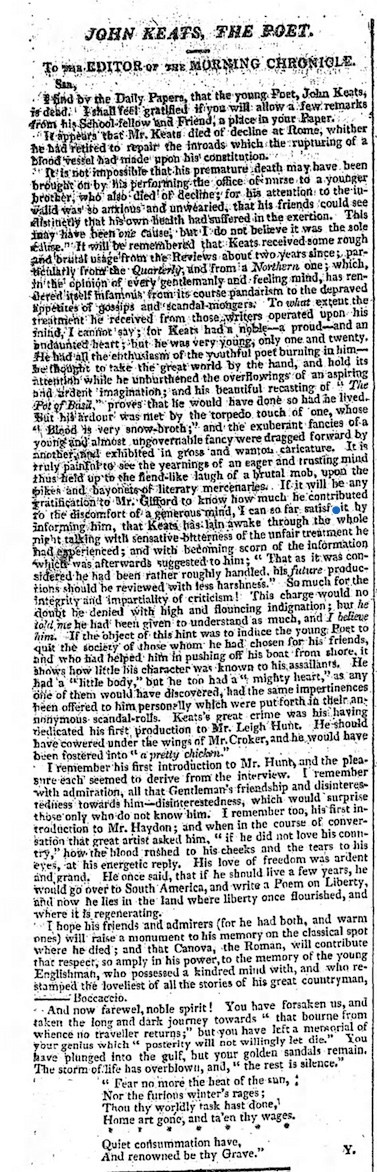

As an example of how one version of Keats’s cultural identity quickly forms, a few

months

after Keats’s death, an anonymous letter in The Morning

Chronicle (27 July 1821) from Y

makes plain some of the growing reputational

complications. (Y is quite likely Edward Holmes,

who went to school with Keats, and moved within Keats’s circle into his adult life.)

Y first

suggests that Keats’s early death may have been set off by his heroic and anxious

suffering in

unsuccessfully trying to help his youngest brother, Tom, fight off consumption. Y

then notes

that Keats did receive rough and brutal usage

from the partisan literary community, but

Y at first seems to be uncertain if this impacted Keats. This is immediately paired

with the

comment that young, enthusiastic Keats had a noble—a proud—and an undaunted heart,

and

that, with the sensibilities of the poet burning

within him, he thought to take the

great world by the hand, and hold its attention while he unburthened the overflowings

of an

aspiring and ardent imagination.

The letter moves on: It is truly painful to see the

yearnings of an eager and trusting mind thus held up to the fiend-like laugh of a

brutal

mob, upon the pikes and bayonets of the literary mercenaries.

Y recalls how Keats could

not sleep because of the unfair treatment.

But, Y declares that Keats’s detractors did

not know the measure of Keats’s strength and the resolve of his character: as Y puts

it, Keats

may have had a little body,

but he had a mighty heart.

Y also recognizes what we

might call Keats’s original sin: Keats’s great crime was his having dedicated his first

production to Mr. Leigh Hunt.

Y also describes how, when Keats is questioned about his

feelings for his own country, the blood rushed to his cheeks and tears to his eyes at his

energetic response. His love of freedom was ardent and grand.

In the end, Y pronounces

that posterity will not let the genius

of this noble spirit

die. So there, early

on, we have a certain, ranging version of Keats: forever youthful, noble, heroic,

naive,

extraordinarily sensitive, strong, honest, freedom-loving, trusting, intense—but in

the end, a

victim of brutal, killing forces, a genius with high hopes that the world might give

some

attention to such mighty imaginative spirit housed in such a little body. With this

picturing

of Keats, it is easy to forget that most of the public commentary was, while he was

alive,

mainly positive and, when not, neutral and generally encouraging of his considerable

potential. [For the facsimile of Y’s letter, click here.]

But beginning in the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth, and now into our own century, critical assessments have, thankfully, turned more often to the question of Keats’s poetry rather than to inflected quarrels over personality. This could only happen when conceptions of Keats went beyond the attitudinal poles and lenses of condescension and defensiveness. Nevertheless, critical camps will come and go in the spirit of massaging what Keats and his poetry means (or what we want it to mean), but at least the question of Keats’s poetic achievement will, one hopes, remain relatively undoubted.

Where does this take us? Well, perhaps to a position that all visions and revisions of Keats exist simultaneously, whether it is the impressionable, sensitive young man or the driven and then highly original poet whose determined rise to maturity is both rapid and remarkable. He can be the writer whose work expresses something between the liberal, progressive, or even radical politics of his day, or he can be seen as a poet who, in his very best work, very consciously avoids such limited and limiting contextualization. A point sometimes lost: Because Keats’s deliberately fashioned this final themes and ideas to be more transhistorical than, alas, culturally relevant—to be, as it were, bigger than his own moment, his own circumstances—they obviously apply more to all time than to his own his time, though grinding Keats into his context (often hyper politicized) is a critical trend of our own era—perhaps, as some might say, as the attempt to justify the material worth of critical practice. No doubt his earlier work (that is, the vast majority of Keats’s total poetic output) is tethered to plain, immature striving, to the flora, fauna, and sweet sentiments of fashion, and to the limiting perceptions of Regency suburbanism and sociability; here some contextualization does help us identify this restricting strain and qualities in his work, and we can see how this can spin off into the era’s cultural tensions that Keats’s poetic progress plays out—the tensions between popular culture and high culture, between poeticisms and poetry. Keats, thankfully, becomes greatly aware of these complexities; and preparing his Endymion for publication offers a strong signal to himself what he needs to do (or rather, not what to do!) in order to progress as a poet. And, at least initially, it never did Keats’s critical reception any good to come off as anti-Alexander Pope.

As this site attempts to show, it becomes clear that, particularly in late 1817 and through into 1818, Keats begins to critically comprehend, for example, the varied but durable poetic qualities, subjects, and accomplishments of Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth. Keats, in this last phase of writing (almost exclusively 1819), attempts to articulate bigger themes in and through his own, hard-earned poetic character; and within these themes, the hope that poetry can somehow free us from the burden of our destined state of in-betweenness—that state of time still and time moving, whether on an ancient urn, in that forlorn moment between waking pain and easeful death, in the lingering state of a pale, bewildered knight on a cold hillside, with the fate of two estranged lovers forever fleeing into a winter storm, or within the stilled yet moving qualities of a season that seems so perfectly self-possessed. Also, think of that hand Keats holds out to us while he at once imagines himself both dead and alive: here it is, he says, beckoning to us from within and beyond the grave. Keats best work is thus dedicated to long history, to the mystery of all that we do not know but must bear, and to imaginative capabilities that reflect the deep, paradoxical power of uncertainty. This, for Keats, is the only real human condition.

What we see over the course of Keats’s poetic progress are his early and often ineffectual struggles to represent the burdening tensions between experience and poetry (and art); and then, in his final phase of writing, his ability, as a poet of risk, to transform those tensions into sites of remarkably tempered creative explorations. But this will not just be a change in Keats’s thinking; it will be accompanied by equally remarkable changes in style and form—those crowded, overly poeticized lines and phrasings will largely disappear. If we like final words on things, perhaps his accomplishment comes down phrasing we can borrow from Keats himself: the achievement of fine excess. Fine, indeed.

In the end, although Keats’s life still leaves us with much to ponder and explore,

it is the

enduring, complex quality of his poetry and that remarkable poetic progress that returns

us to

a name that, although writ on water,

is indelibly written into literary history and

art—writ large, actually. Even before Keats writes the poetry that almost wholly establishes

his reputation, that yearning Passion

he has for the beautiful

moves him toward

where he believes he will be—and where now he is: I think I shall be among the English

Poets after my death

(letters, 14-31 Oct 1818). In fact, his presence goes even beyond

that.

My thanks to Luca Caddia at Keats-Shelley House in Rome for the image of Keats’s death mask; and to Nicholas Stanley-Price on the Advisory Committee of the Non-Catholic Cemetery in Rome for clarifying who was responsible for designing Severn’s headstone.

Animation comparing Keats’s life and death masks: