23 February 1821: The Death of a Poet: Youth Grows Pale, and Spectre-thin, and Dies

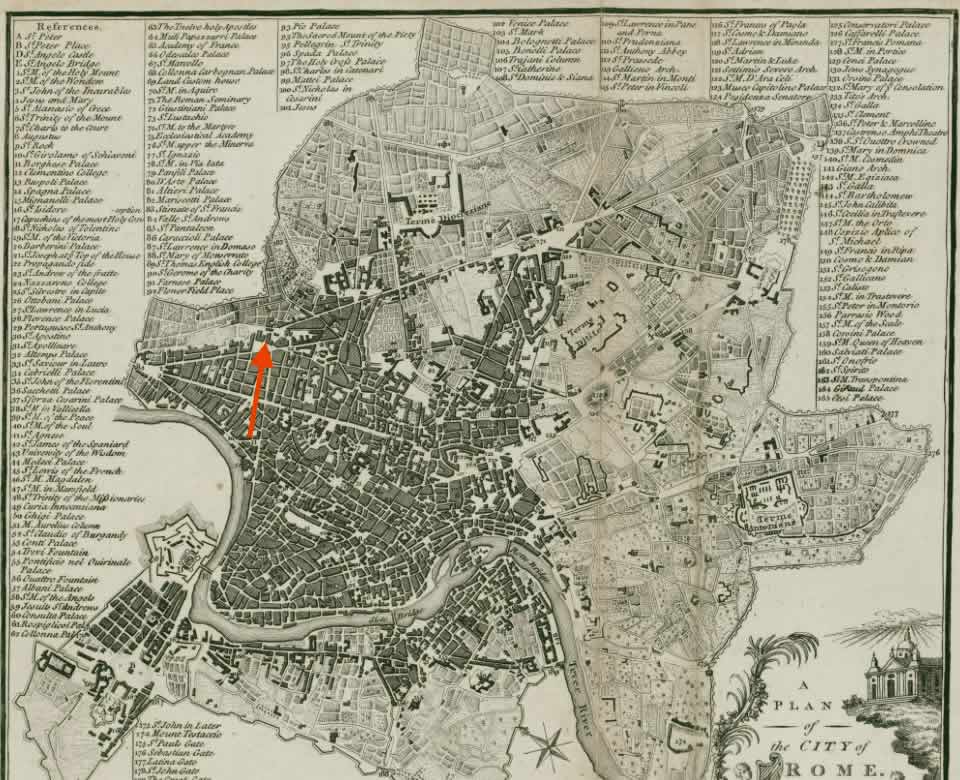

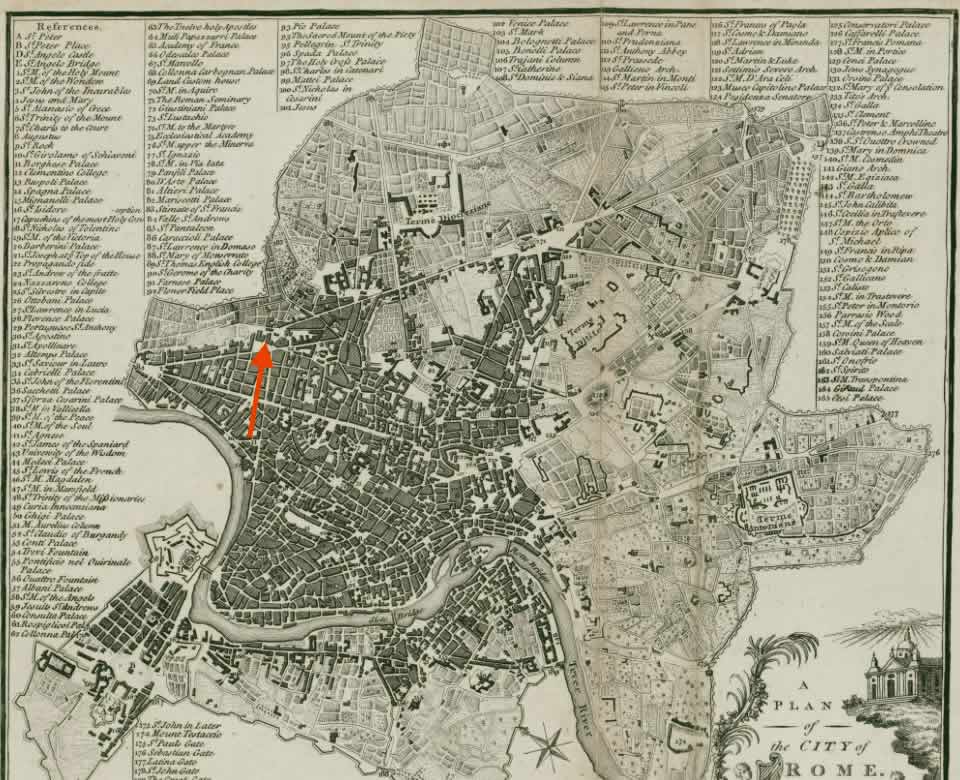

26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome

In a small room at 26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome, at approximately 11:00 pm on the night

of 23

February, Keats, aged twenty-five, dies of consumption. His last months are horrible:

the

wasting disease

—pulmonary tuberculosis—has worked itself from his lungs and into his

stomach, with possible origins in his throat, which can happen as the TB bacillus

spreads

through the blood stream. Emaciated, often in pain, and with his body fevered in a

vain

attempt to fight off systemic infection, Keats vomits and coughs up blood, only (at

least

initially) to be bled by his physician and put on a frighteningly restricted diet.

Despite its

romantic associations, sometimes fetishized by Victorians as having some morbid aesthetic

appeal, tuberculosis is a horrible killer, and the cheerless physical atrophy hardly

appealing.

The first clear sign of consumption comes a year before, on 3 February1820, also

at 11:00 at night: after a chilling ride on an open carriage, Keats experiences a

hemorrhage; he comments to his very good friend, Charles Brown, who helps him into

bed, that the presence of arterial blood

signals his death-warrant. I must die.

The reference to arterial blood may be to its colour: Keats observes that it is likely

from his lungs, which, he knows, is a bad sign.

Since leaving England mid-September 1820, Keats is tended by his friend, the young

painter Joseph Severn, who now begins to suffer from emotional and physical exhaustion.

The day before Keats passes away, Severn, distressed, drained, and helpless, writes,

my intellects and my health are breaking down—I can get no one to change me—no one

will relieve me—they all run away—[ . . . ] he has sunk in the last three days to

a most ghastly look.

Severn constantly lifts Keats in the fear that Keats will choke on the fluids that

build up in his throat.

According to Severn, Keats’s only vague relief

comes when, after Keats opens his eyes in great horror and doubt,

he sees Severn by his

side. Keats, in fact, records exactly the same circumstance in nursing his younger

brother,

Tom, through the same illness: about six

weeks before Tom dies, Keats writes, Tom [ . . . ] looks upon me as his only comfort

(14 Oct 1818). About two weeks after Keats dies, Severn reports how Keats hoped for

the

quiet grave—O! I can feel the cold earth upon me—the daisies growing over me—O for

this

quiet—it will be my first

(6 March). Severn has also had to cope with Keats’s

determination to commit opium-induced suicide, since the suffering is so great and

his fate so

clear—and (what Severn calls) the cursed bottle of Opium

so apparently near.

For a moment, Keats’s poetry returns to us. An hour before midnight on 23 February

1821,

Severn describes Keats’s final moment: his

eyes look’d upon me with extreme sensibility but without pain

(6 March 1821). This

uncannily recreates the poet-speaker’s condition in Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale,

who

feels as if he has emptied some dull opiate to the drains,

and who expresses the desire

to die easefully and unseen, To cease upon the midnight with no pain

(56). So, too,

does Keats’s description of human suffering in the poem present us with a clear picture

of

consumption: The weariness, the fever, and the fret [ . . . ] Where youth grows pale, and

spectre-thin, and dies

(23-26). Keats no doubt wrote this (in May 1819) thinking of poor

Tom, but now this condition and moment is upon him. The universal and the personal

are one—in

the hands of a great poet, that is.

By picturing Keats on his deathbed, and by picturing Keats as an intimate witness

to the

agonizing wasting away of Tom from 17

September until 1 December 1818, an important characteristic of his greatest poetry

returns to

us in a context that helps to account for and describe Keats’s rapid poetic progress

in early

1819. That is, this picturing

puts into relief how Keats comes to empathetically and

then imaginatively translate the meaning of suffering, death, and the human condition.

Before

1819, Keats purposefully explores the subject—in, for example, his wrestling with

William Wordsworth’s vision and depth; and in

gauging Shakespeare’s magnitude, range, and

apprehension, in, say, King Lear, which, in Keats’s own words

in his sonnet about rereading the play, points to the play’s definitive tackling of

the

fierce dispute / Betwixt damnation and impassioned clay.

Importantly, the sonnet

expresses Keats’s need to leave behind the trappings of Romance

in order to address

themes tied to the darker moments of the human condition.

Keats, then, before 1819, knows what strong, enduring poetry requires: the restrained and imaginatively capable representation of the depths and nature of human suffering in the context of time, immortality, and artistic grace—in the truthfulness of beauty and the beauty of truthfulness. However, his previous work has for the most part immaturely addressed but largely bypassed these crucially commingled subjects.

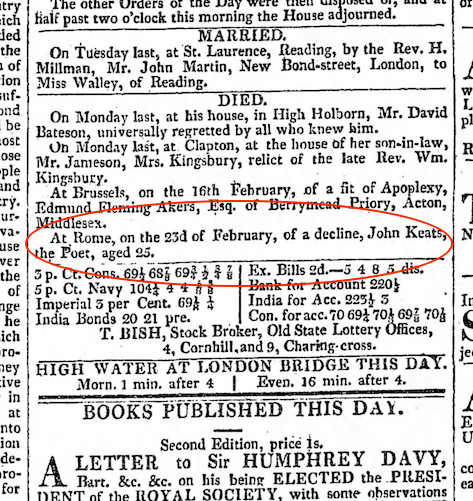

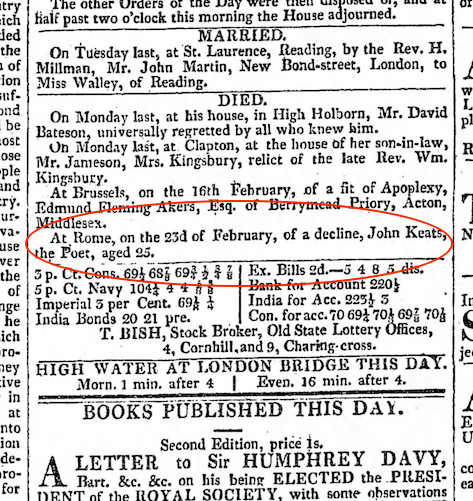

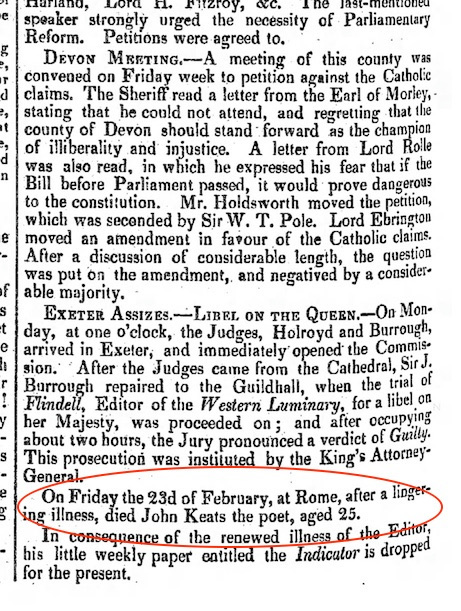

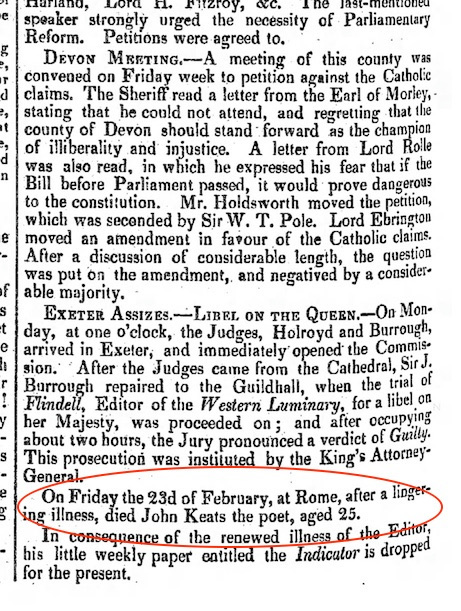

of a decline,in The Morning Chronicle, 22 March 1821

And so Keats’s only year of great poetry—1819—follows shortly after Tom’s death, and the resulting poetry, anticipated by his poetics expressed in his letters, signals his new artistic comprehension; and those subjects (human suffering, immortality, and poetry that intermingles and collapses beauty and truth) begin to show up not just with great poetic control, but with a credible, settled tone that measures intensity with restraint and creative detachment. Keats now writes without egotistic striving and in forms (primarily in lyric mode) that avoid the arbitrary and affected manner of almost all of his earlier poetry. Intensity and excess are finely balanced by an unobtrusive voice.

after a lingering illness,in The Examiner, 25 March 1821

An abridged and greatly simplified chronology of Keats’s progress might go something like this: Through very deliberate study of enduring poetry, through equally deliberate trials of composition (Endymion being the most obvious, as well as poetry that immaturely advertises Keats’s desire to be a poet), and through circumstances both sought and unsought (becoming part of a varied and engaging intellectual network, facing the death of his brother), over 1817 and 1818 Keats articulates a theory of the poetic character; and in 1819 he acts upon that recognition and begins to translate that theory into poetry. A more abridged chronology might go like this: Keats was first of all a poet in search of a subject; then a poet in search of how to express that subject; and finally, a poet whose poetry embodies its subject—fully, uniquely, and without poeticized over-reaching. He writes with controlled intensity, and with forms that complement the subject, rather than distracting from it. This poetic achievement, though in some ways sounding both simple and sensible, is both hard-won and rare.