16 August 1820: Sinking with Shelley

From Italy: Shelley to Keats, then Keats to Shelley

During August, Keats, aged twenty-four, has deepening and accumulating worries. In letters he feels the brutal world is simply too much for him, and that he has no future; death, he thinks, might be his only rest.

What takes Keats to this particular moment?

First, he has his mounting illness that is now tied to the idea of going to Italy

in a vain

attempt to rescue his failing health; he reports that his chest is in a bad state

and that he

been haemorrhaging. Second, with that travel plan to Italy, he has desperate fears

about

leaving his beloved Fanny Brawne: he writes to

her during the middle of the month to say that he cannot leave her, and that if he

cannot live

with her, he will live alone. His future? Nothing but thorns,

he writes, suggesting

both confusion and suffering. Third, if he does go, who should go with him to Italy?

His best

friend, Charles Brown, is away and cannot be

immediately contacted. Fourth, if Italy is his one hope, there is the problem of money:

he has

none; and the overseer of his family money, Richard

Abbey, will write to Keats that it is not in my power to lend you any thing

(23 August). But his publishers, Taylor & Hessey, come to rescue by buying copyright

over

his earlier work as well as crediting him with some money for future sales. This is

an

extraordinarily kind act by those who believe in Keats. On 14 August, it is to Taylor that Keats sends the basis of his will.

Mid-August also provides some final word on Keats’s self-assessment of his early poetry.

The

context: Percy Shelley, Keats’s implicit poetic

rival and acquaintance, upon hearing of Keats’s illness, had written 27 July to generously

invite Keats to stay with him and his wife, Mary, in Pisa, or at least in its

neighbourhood.

Shelley vouches for the restorative air, the fine natural environment,

and cultural surroundings. (Shelley’s letter is sent to Keats c/o Hunt’s Examiner

office on Catherine Street, London.) With a flattering wink, Shelley comments that

an an

English winter

would be healthy for a writer of such good verses.

Shelley’s

wording and tone moves between familiarity, touches of humour, serious sympathy for

Keats’s

precarious health, praise for the treasures of poetry

Endymion contains,

and Keats’s capability of the greatest things.

But there is also some not-quite couched

criticism of those treasures

in Keats’s long poem: they have, Shelley comments, been

poured forth with indistinct profusion.

Well, Shelley is quite right, and, in truth,

he puts it very well: the poem does indeed contain many parts that seem somewhat random—parts

that overflow with overly poeticized moments determined more by rhyme than by reason;

the poem

does much undirected wandering, as even Keats himself realizes. Shelley goes on to

write that

in his own poetry, I have sought to avoid system & mannerism.

In short, Shelley implies that Keats is a poet of potential.

Now, we have to imagine how Shelley’s words might rub Keats. After all, Shelley, like

Keats,

is hardly an esteemed, legislating voice of poetic tastes and authority. That is,

Shelley,

though a little older than Keats, does not really hold much or even any poetic seniority

over

Keats, though we have to believe that Shelley’s motives are formed more by critical

honesty

than anything approaching malice. But this would not change the niggling impact of

the phrase

to Keats—poured forth with indistinct profusion

—who has just published a collection

that completely dwarfs the qualities of his two earlier books.

From Hampstead, Keats writes back to Shelley on

16 August. The letter (it looks and sounds unhurried and deliberate) is almost exactly

the

same length and form as Shelley’s; he will send it via mutual friends (the Gisbornes),

who

arrive in Italy about the second week of October. In the letter, Keats acknowledges

Shelley’s

invitation, and agrees (using Shelley’s own phrase) that an english winter

would indeed

put put an end

to him. But he politely but obliquely notes that he will not likely

take advantage

of Shelley’s invitation; and we might recall that this is not the

first time Keats has made it clear that he wants to keep some distance from Shelley’s

influence: almost three years earlier, Keats writes to a friend that he had refused

to visit

with Shelley because he wanted his own unfettered scope

(to Bailey, 8 Oct 1817); the same, then, still holds.

Keats doesn’t take long to respond to Shelley’s mixed criticism of Endymion, which Keats calls his poor

Poem.

Keats adds that if he cared more about literary Reputation,

he would

willingly take the trouble to unwrite

it. Keats understands the significant flaws in

his poem, and this is not the first time he has announced them, though it may be the

last.

Keats then acknowledges receiving a copy of Shelley’s Cenci via Hunt, which Keats

apparently took some trouble to read carefully, making some notes in it (this marked-up

copy

is, alas, lost). Keats musters some defensive posturing, given Shelley’s not-quite

guarded

critical remark about Keats’s early poetry. Keats is less subtle in his comment about

Shelley’s own poetry, and he cleverly peppers it with some advice: you might curb your

magnanimity and be more of an artist, and

Keats almost apologizes for this comment, understanding that, for Shelley, such

load every rift

of your subject with

ore.discipline must fall like cold chains upon you, who perhaps never sat with your wings

fur1’d for six Months together.

Keats is right: Shelley’s life and poetry could

certainly be defined by unsettledness and high-flying! Keats is self-aware enough

to add that

his comments could easily be turned upon himself: he characterizes his own mind as

a pack

of scattered cards.

But Keats cheekily throws in a bit of serious reflection and

profitable obscurity Shelley’s way: My Imagination is a Monastery and I am its Monk—you

must explain my metap[hysics] to yourself.

Keats must have been carrying around something of Shelley’s words from three years

earlier,

when Shelley advises Keats not to publish his early work, meaning the 1817 Poems by John

Keats collection: Keats writes, I remember you advising me not to publish my

first-blights [. . .] I am returning advise upon your hands.

Turnabout, he suggests, is

fair play.

Keats follows to say that he will send Shelley his new 1820 Lamia,

Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems volume (published a month or so

earlier). Keats adds to Shelley that the poems in the 1820 collection are more recent

compositions, but were only published, he writes, but from a hope of gain.

Keats thus

plays down the quality of the collection; but we have to consider the obvious: given

the

present exchange between the two poets, Keats would hardly send inferior or immature

poetry to

Shelley. Keats is indeed right to feel that the 1820 volume is an improvement over

his earlier

work—in fact, he is frighteningly right. For us—for him—it both sadly and triumphantly

represents his ultimate progress.

Hunt writes to Shelley on 23 August that Keats will call on him in the spring 1821. Keats does not make it that long.

And two final connections between Keats and Shelley also centers around death.

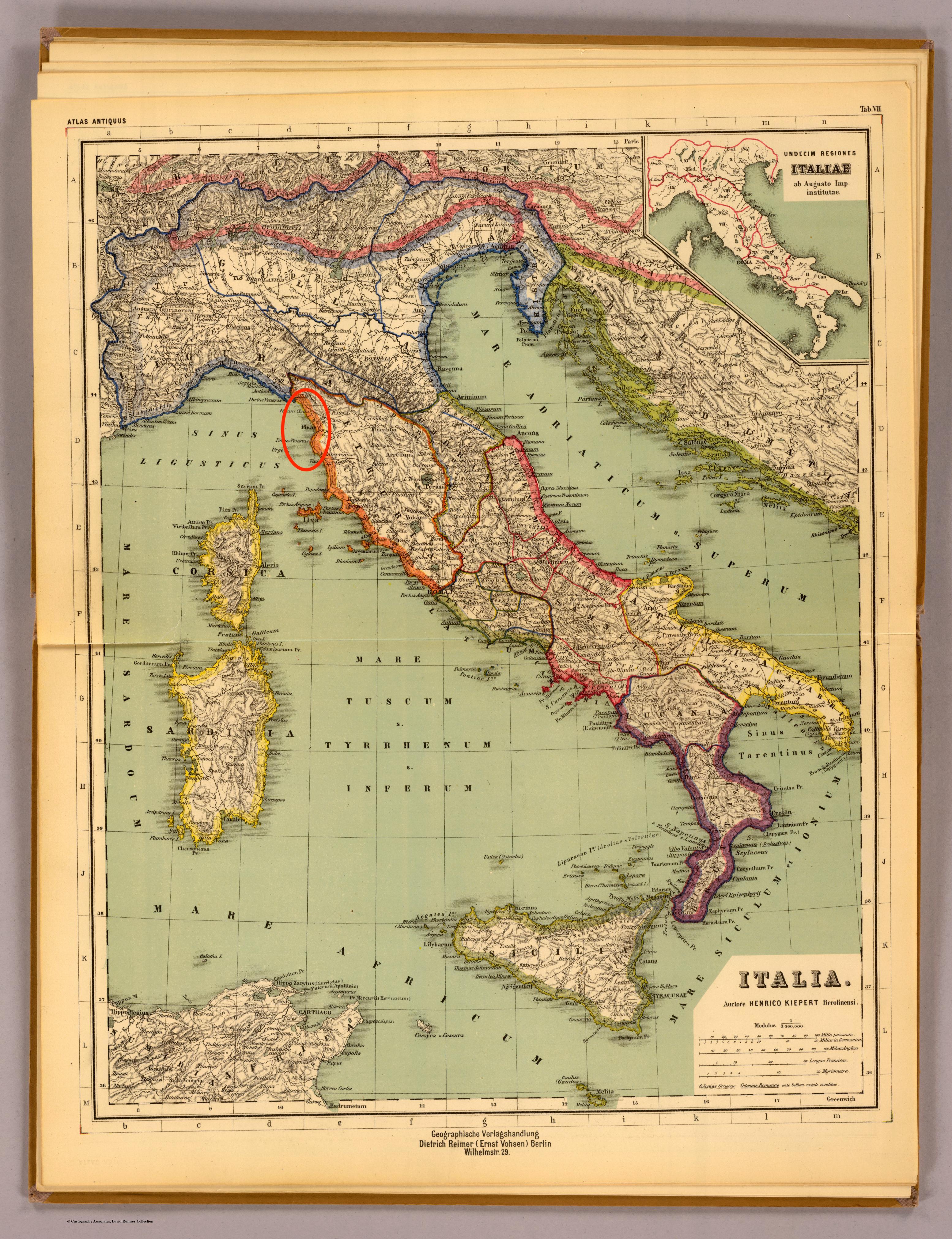

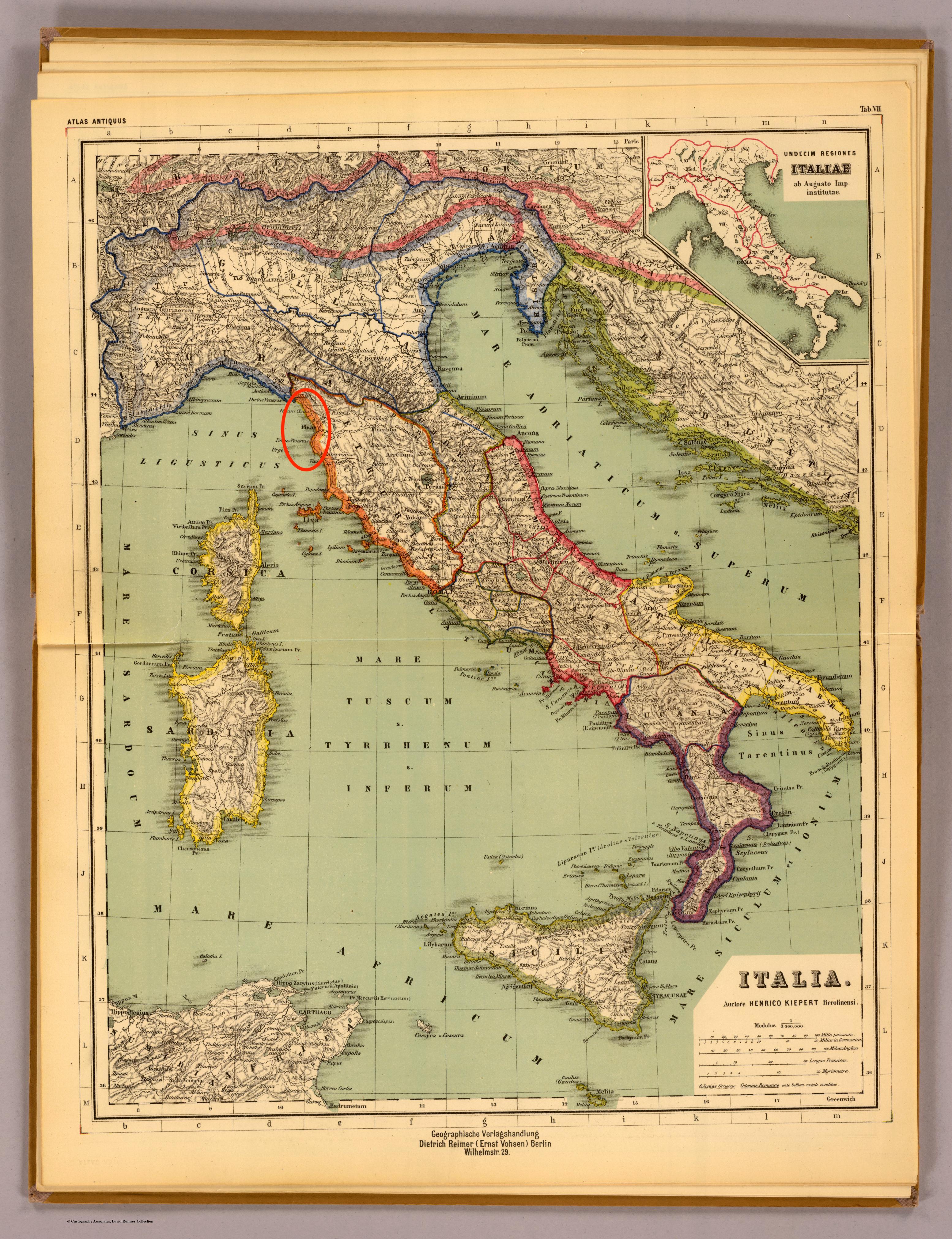

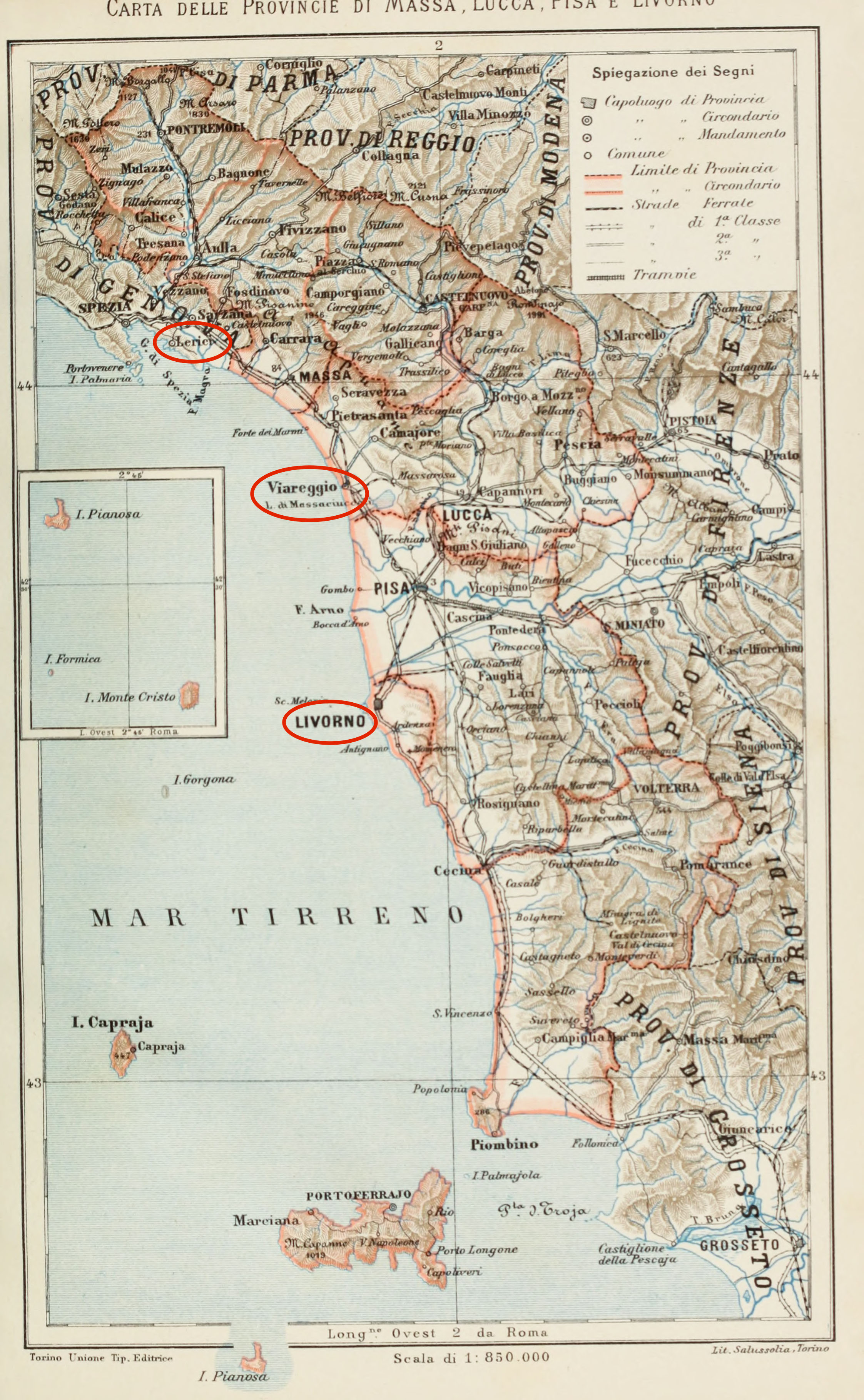

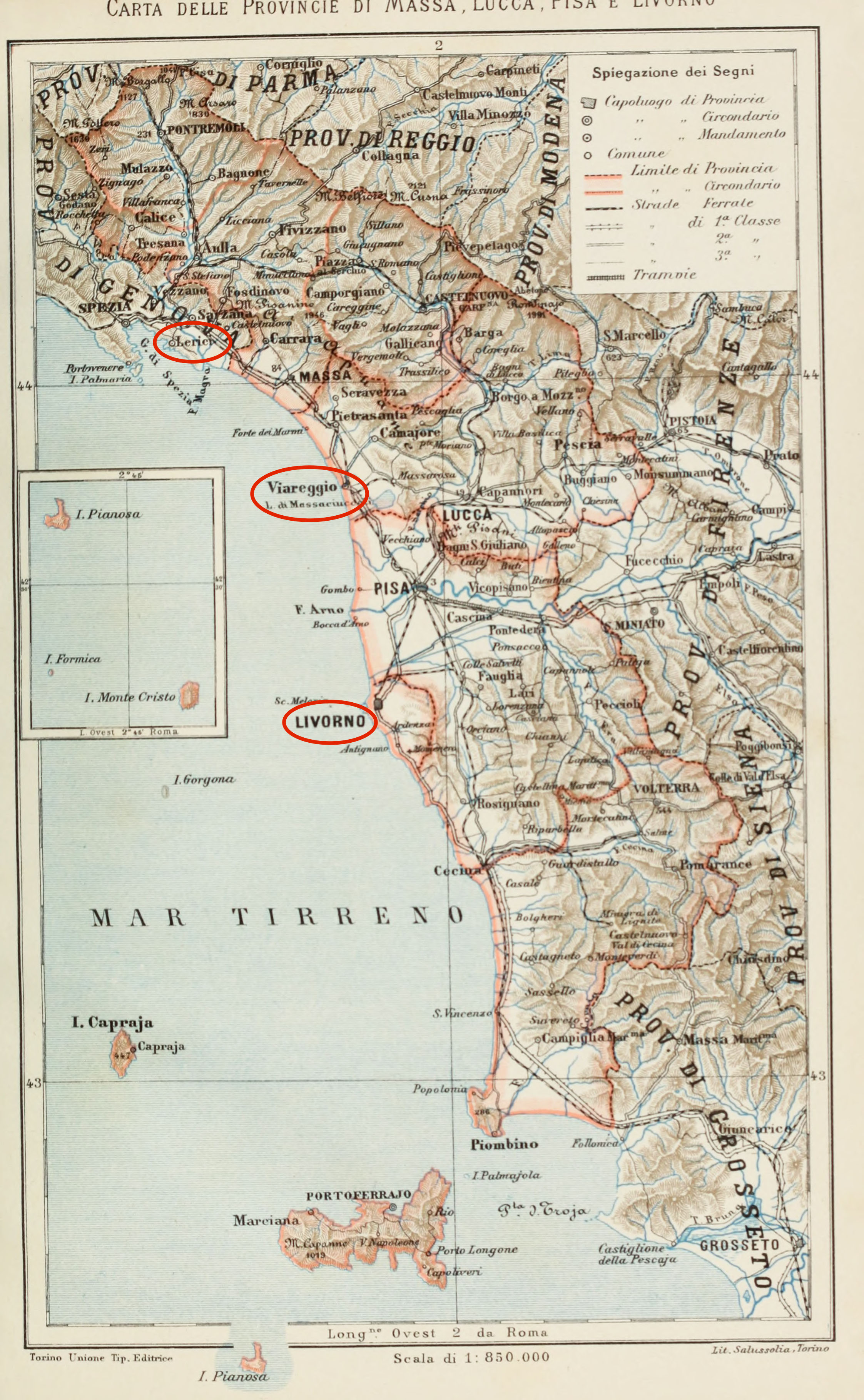

Two years later, on 8 July 1822, twenty-nine-year-old Shelley, along with two others, returns from Livorno to Lerici aboard his over-powered 24-foot twin-masted yacht, the Don Juan; it is overtaken by a severe storm; the heavily-ballasted and deckless boat (with little clearance) is ill-equipped to handle rough sea; they do not seem to have lowered their sails when the storm hits. The boat sinks; all three passengers drown. Ten days later, the three decomposed bodies will be found on the beach, fairly close to Viareggio, which is about half way between Livorno and Lerici.

Shelley’s body (likely identified because of his clothes) is found with Keats’s 1820 collection in his jacket pocket; it was Hunt’s copy. The spine of the book seems to have been broken (by accounts, double-backed), suggesting that Shelley, at the last moment, likely crammed the volume into his pocket just before the boat sank. Later, 16 August, Shelley’s body will be cremated on the beach, along with Keats’s book; his ashes will be buried in Rome in a more formal funeral, not too far from Keats’s grave site. We might assume, then, that the very last thing Shelley reads before he drowns is Keats’s poetry—that magnificent final volume. And perhaps, too, we can be a little dramatic, poetic, and morbid here, and imagine the last lines Shelley reads are from Keats’s Ode to a Nightingale, where the pervasive imagery is that of sinking unseen toward darkness and death. Poor Shelley; poor Keats.

And lest we forget: it will be Shelley who writes the most extended and marvellously complex poetic elegy to Keats—the 1821 Adonais, a poem that, interestingly, probably tells us much more about Shelley and his ideas about poetic greatness than about Keats. Keats’s death is blamed upon the slings and arrows of outrageous criticism rather than the most pervasive killer of the age: a slow-growing bacterium.

And that second but more oblique connection between Keats and Shelley involving death?

In

early June 1819, less than two years before Keats dies, Shelley’s 4-year-old son William

(Willmouse

) will die and be buried in the Protestant Cemetery, Rome, where Keats will

also be put to rest, 26 February 1821. And, as mentioned, Shelley follows in 1822.

[For more about Shelley, see 16 August 1820 and 18 November 1817.]