6 May 1820: Keats’s Accumulated Anxieties & the Too Great Excitement of Poetry

2 Wesleyan Place, Kentish Town

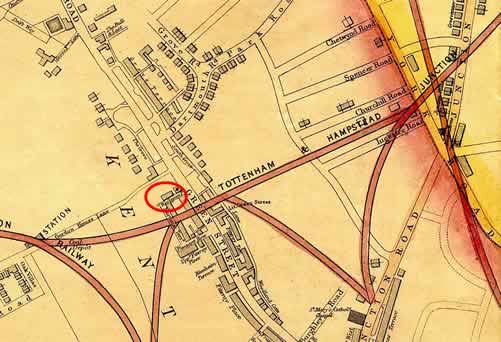

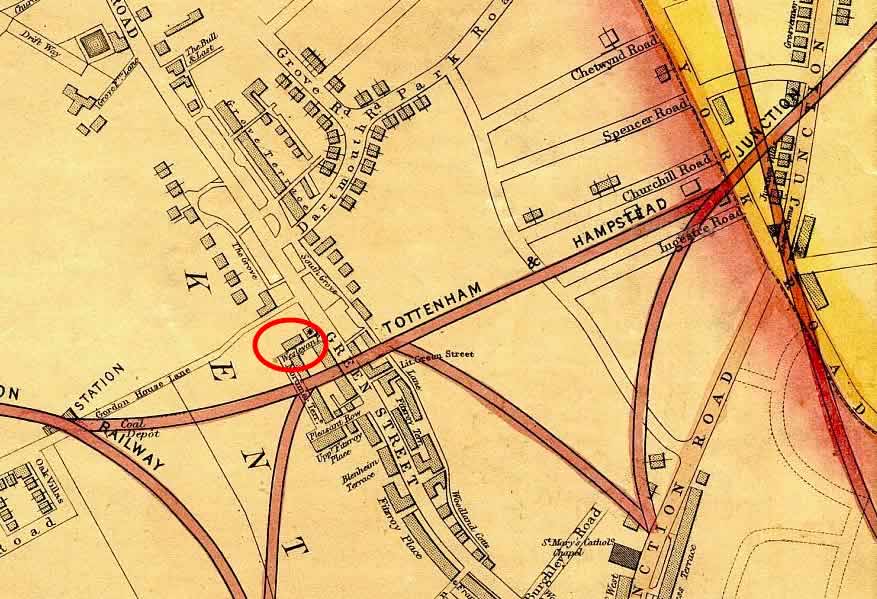

Keats moves to 2 Wesleyan Place, Kentish Town from Wentworth Place, Hampstead, where he stays for about seven weeks. The move is not that far, Kentish Town being just on the other side of Hampstead Heath. Keats leaves Wentworth Place because his very good friend, Charles Brown, has had to rent out his half of the double-house. Brown, who has already been very generous with Keats, loans him 50 pounds on this day.

Through March and into April, Keats is in imperfect health, and no doubt has signs of consumption (tuberculosis), with the problem likely migrating from his throat into his chest.

The merging of physical symptoms with issues of nervous anxiety only intensifies Keats’s

condition. In a letter of 21 April to his younger sister, Fanny, Keats reports that a doctor, quite remarkably, tells him there is nothing

the matter with me except nervous irritability and a general weakness of the whole

system

which has proceeded from my anxiety of mind of late year and the too great excitement

of

poetry

(21 April)—this despite his earlier blood-spitting, which returns in June. Keats

in May expresses that he is afraid to ruminate on any thing [ . . . ] difficult or

melancholy

since it is so pernicious to health

(letters, 4 May). Keats reads his

own condition better than the doctors. What we have to imagine is quite revealing:

Keats

clearly must be communicating his intense devotion to poetry, even to physicians,

who see this

as a significant component of his behavioural and physical difficulties.

Keats’s thoughts about and communications with Fanny

Brawne become increasingly uneven: he places aches and torments upon her, along with

jealous, controlling ultimatums. He writes things to her like, You must be mine to die upon

the rack if I want you.

Keats, then, has significant overlapping stressors:

- serious and continuous financial pressures and uncertainty;

- continuing difficulties with the generally inflexible trustee of the family estate, Richard Abbey, and significant confusion about how much he is entitled to (he’s unaware of money available to him via the court);

- uncertain prospects as a wage earner;

- fears that intense composition and thinking will compromise his health, that thinking

deeply about anything

which has the shade of difficulty or melancholy in it

may damage his health (letters, 4 May); - lack of success and credibility as a poet and playwright, despite his lingering desperation for recognition;

- increasingly possessive and tormented desire for but doubts about Fanny Brawne, his

betrothed; in May, in a tormented mood, he writes to Fanny that his

whole existence hangs upon [her . . . ] you must think of no one but me [ . . . ] For god’s sake save me—[ . . . ] O the torments!

; - that his friends generally disparage Franny Brawne;

- recent loss of or separation from family: his younger brother Tom dies of tuberculosis in December 1818; his other brother, George, who emigrates to America June 1818, has recently come and gone, in order to return with renewed finances from family money; Keats also has little sustained contact with sister, Fanny, who is often sequestered from him by the family guardian, and Keats is increasingly upset with treatment she receives (15 May); both his parents are dead;

- fear of cold and wet weather—and even being out at night;

- disenchantment with London and with some of his friends, despite strong support from many of them;

- lack of full control over publication details of his forthcoming collection;

- and then great tension over those serious health issues, particularly related to his

chest, which no doubt gives Keats cause to fret about his immediate future.

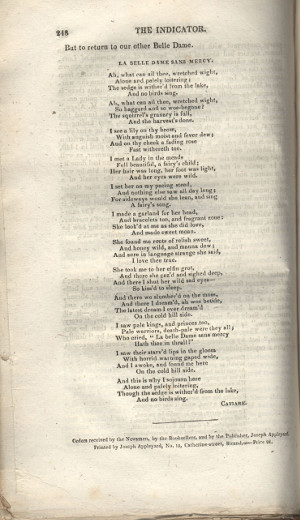

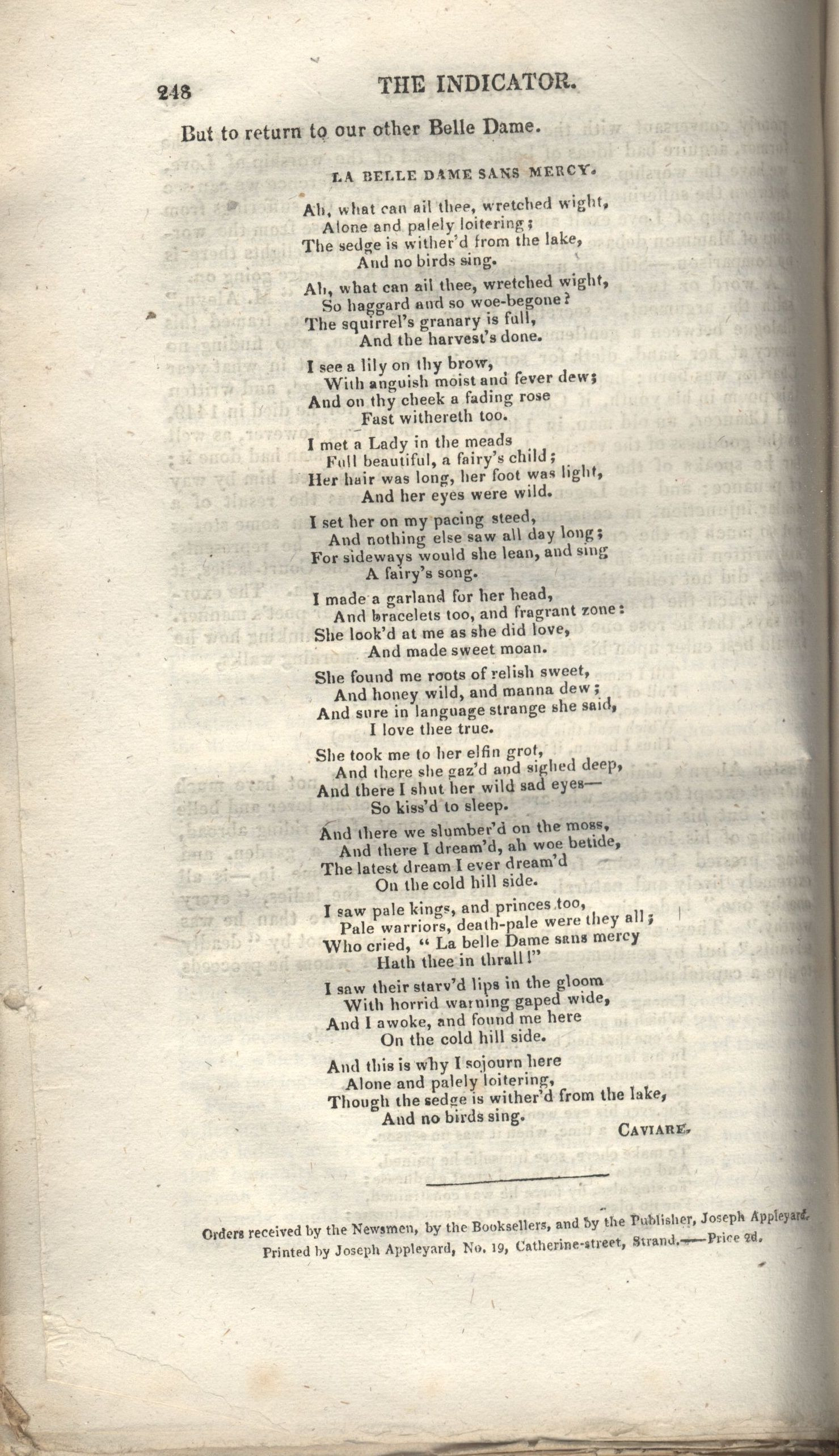

But there is at least something: On 10 May, Keats’s haunting and richly allusive ballad La Belle Dame sans Merci is published in The Indicator, which is Leigh Hunt’s new literary magazine (launched October 1819). The poem is likely written in April 1819. The short, unadorned narrative ironically expresses the darker side of imaginative capabilities; it allegorizes the position of the questing poet who is seduced by the beautiful, unknowable ideal, and who will, in the end, be left, alone, in his cold, unmoving, and mortal world. In a way, then, the poem also enacts Keats’s situation. La Belle Dame might, in fact, be Keats’s most suggestive and compressed poem: Keats signals how very much he can do with so very little, which is quite the opposite of Keats’s 4,050-line Endymion (mainly written April-November 1817, published April 1818), which displays how very little he can do with so very much. Unfortunately, La Belle Dame is not collected in Keats’s final and remarkable volume, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, published in June.

A bit of other good news for Keats at this moment: a 10-page review of his very long

poem,

the 1818 Endymion,

appears the previous month, in John Scott’s

London Magazine for April 1820.* The review is obviously a

delayed response, but it purposely acts as a strong counter to the exceedingly nasty

and

partisan reviews of Endymion in the Quarterly Review (of April

1818) and in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine (of August

1818); revealingly, it does point to some similar poetic failures of Keats’s epic

romance,

while taking a non-disparaging route in getting at those shortcomings. Scott’s London Magazine review claims that Endymion is not like any other poem; in fact, it is not a poem at all.

It is an ecstatic dream of poetry—a flush—a fever—a burning light—an involuntary out-pouring

of the spirit of poetry—that it will not be controuled [sic] [. . .] It is the May-day

of

poetry [. . .] It is the sky-lark’s hymn to day-break, involuntarily gushing forth

as he

mounts upward to look for the fountain of that light which has awakened him

(p.381).

This high-flying enthusiasm, though, is thoughtfully tempered by also noting the poem’s

glaring faults—faults that in many instances amount almost to the ludicrous,

yet,

paradoxically, the faults and the poem’s beauties are linked by the poem’s youthful,

fevered

pitch (p.382). As Scott notes, Keats, in his hurried exuberance, has jumped into the

ocean of

poetry before he has learned to negotiate rough waters. Despite the rioting randomness

and

confusions in the poem, despite the poem being as full of faults as of beauties

(p.388), there are moments when its imagery, melody, rhythms, and imaginative powers

reach the

accomplishment of early Shakespeare. The

bottom line for the review is both determined and prophetic: He is and must be a poet—and

he may be a great one

(p.389).

*For the story of Scott’s fatal involvement in defending personal and literary reputations, see 16 February 1821.