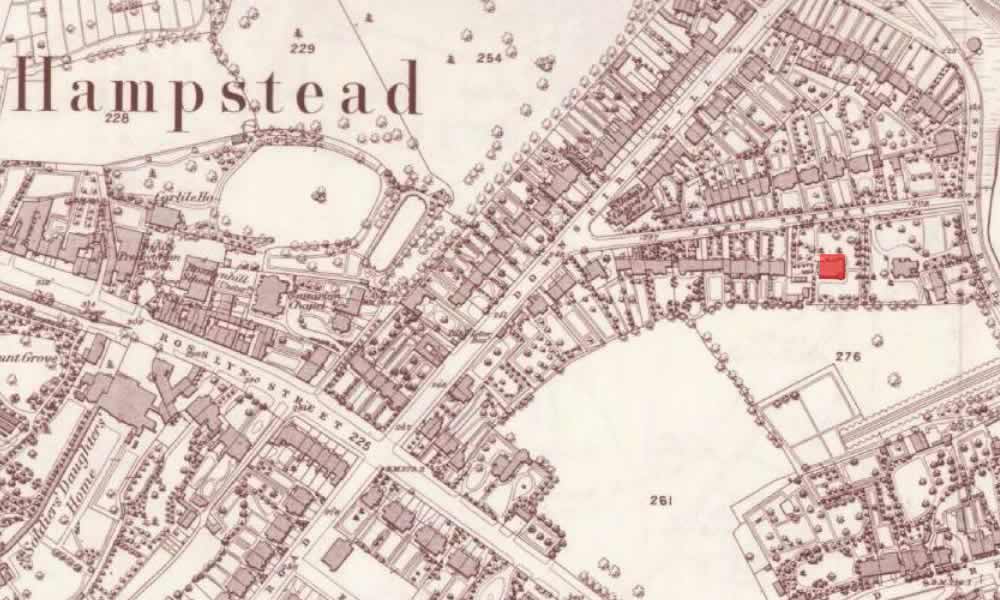

21 October 1819: A Bright Star as Immortal Love; A Living Hand as Emotional Blackmail

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Ten days short of his twenty-fourth birthday and after a brief stay at 25 College

Street,

Westminster, Keats returns to Hampstead and Wentworth Place (a double-house) to once

more live

with his close and generous friend, Charles Brown.

Money, familiar associations, and domestic convenience (it seems he does take well

to petty

housekeeping) may have been the main reasons for the move. To add to his troubles,

Keats has

the bankruptcy of his brother, George, in America,

to sort out: he writes to his sister, Fanny, I

call on Mr. A[bbey] about George’s affairs,

which perplex me a great deal

(letters, ?26 Oct). There are also unpaid bills lurking

and loans to repay. Keats admits, My disposition is of so careless a nature that it is

continually tormenting me for my neglect of matters of consequence

—Keats calls his

neglectful character a disease which at intervals comes upon me like a fever fit

(letters, 2 Nov). Keats also feels that vegetarianism might improve his well-being.

As usual, then, unsettled finances make Keats anxious and his future uncertain: he gets by on loans from friends, and he hopes that a play co-written with Brown, Otho the Great, will soon be accepted and produced in order to generate some money—and perhaps mark his credibility as a writer. The play is submitted to the manager of Drury Lane Theatre sometime around the 22nd, in Brown’s name only. Their hopes never materialize, and the play, with its unavailing hints of King Lear (as well as other unproductive allusions to Shakespeare), is short on drama, long on the theatrical, stylistically forced, and a little confused in both focus and purpose; there are, though, enough elements that a theatre-going Regency audience would have accepted, especially those moments when the play renders itself, as it were, self-conscious of being a play. The plot is mainly Brown’s, and the wording mainly Keats’s. Keats initially believes that his tragedy might have some genuine impact; in fact, it is quite forgettable—so much so that it will be 130 years before it is staged. Keats’s hope for the play continues into early 1820.* [For more on the play, see 11 October 1819.]

Keats’s love for Fanny Brawne now, quite

literally, faces him: she occupies the other half of Wentworth Place with her widowed

mother

and siblings. Keats, of course, cannot help but hear and see her comings-and-goings.

Having

just spent time with Fanny (he stays with the Brawnes for three days in the middle

of

October), and about a week earlier confessing to her that I cannot live without you,

as

well as in anticipation of seeing her soon, on 19 October he writes her a short letter

that

worries over his idleness and the imperative to keep busy: he ends by telling her,

my mind

is in a tremble, I cannot tell what I am writing. / Ever my love yours / John Keats.

Keats and Fanny are, it seems, engaged this month, though it is kept quiet. Keats

knows that

his friends would be (and were) skeptical of the pairing: for them, Keats’s situation

is too

precarious (it is), and Fanny too frivolous (not really).

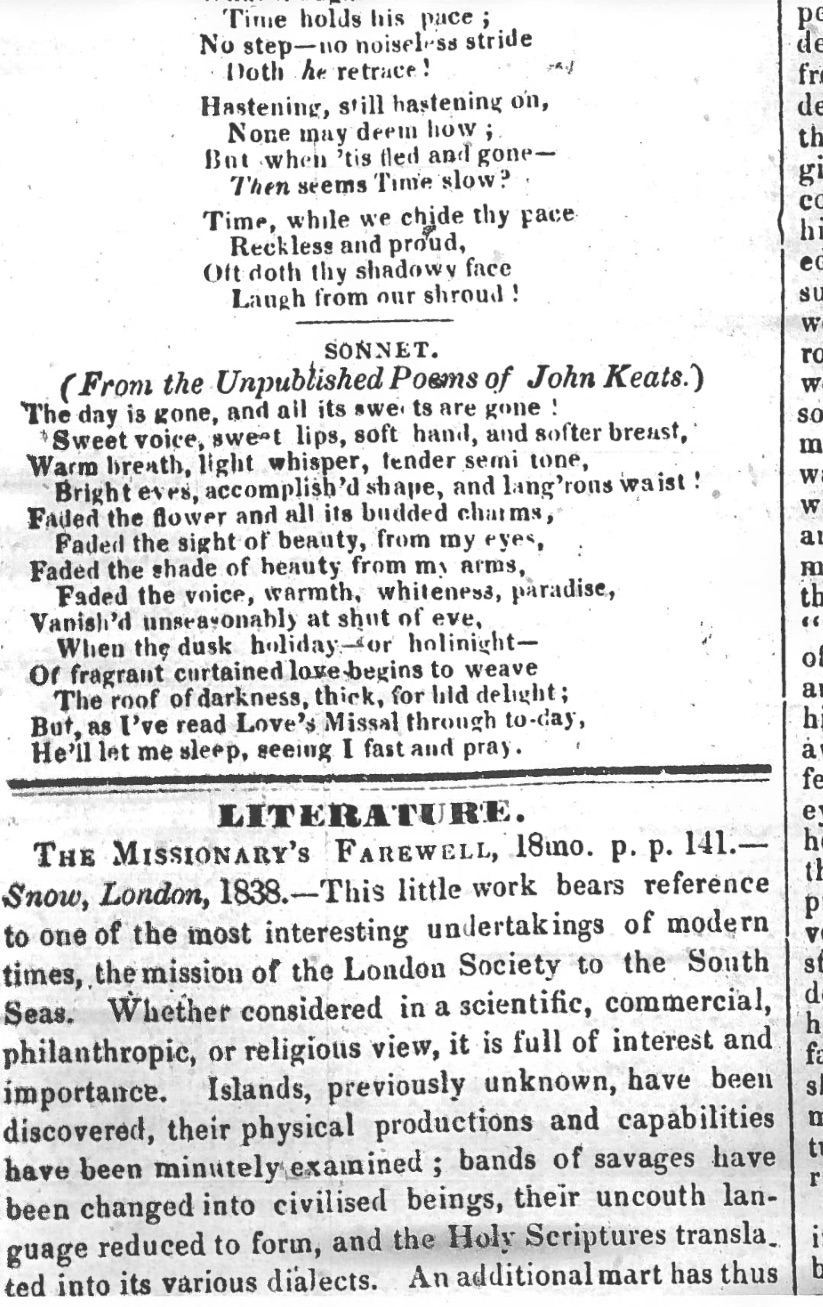

Keats may have written the sonnet Bright Star during the month (see the 11 October 1819 entry), since the poem reflects his desire for physical and emotional steadfastness in his intense but unfulfilled relationship with Fanny. Being so close to her this month no doubt both condenses and disarranges his feelings. In a larger, more universal context, Bright Star beautifully expresses the paradox and tensions of wanting to love forever within (alas!) human and, therefore, mortal confines. Contact with Fanny this month may also have led Keats to write a few minor poems that unevenly grapple with his feelings and thoughts for her—The day is gone, I cry your mercy, What can I do to drive away, and To Fanny.

In somewhat the same impulse, but in a darker, controlling mood, Keats around this time or into November (but certainly before the end of the year) composes This living hand, now warm and capable, an eight-line poem he writes on paper used for drafting The Cap and Bells, an 800-line, unfinished, comic-spirited poem with a satirical edge. The two poems could not be more different—proof that size does not matter. The longer poem is also known as The Cap and Bells; or, The Jealousies. A Faery Tale. According to Brown, Keats apparently preferred the title, The Jealousies, and from all we know, Keats composes the poem (in Spenserian stanzas) quickly and with some enthusiasm; though variable in its movement and qualities, it does at least display Keats’s developed dexterity in voice, character, and narrative, building upon at least part of the accomplishment of The Eve of St. Agnes, though not nearly as evocative.

This living

hand is a short, intense, and even morbid poem, something like William Wordsworth’s enigmatic She dwelt among the untrodden ways and A

slumber did my spirit seal (the latter is, like Keats’s poem, also only eight lines).

Death, longing, separation, uncertainty, and guilt likewise haunt Keats’s condensed

lyric,

though Keats might have composed the lines as some kind of shell for a sonnet. So,

too, do

imagistic and emotional tensions force the drama of the poem forward: living/dead,

warm/cold,

day/night, dream/reality, dryness/streaming, regret/hope, desire/fear. With its brevity

and

with the final line ending mid-line after only three beats (six syllables), the blank

verse

poem looks like a fragment, but it is not: the way it ends—with the waiting hand held

out to

the addressee, and us, See, here it is - / I hold it towards you

—shows that it is, with

its concentrated emotion, complete in thought, feeling, and sensation. The poem says,

in

effect, Here is my hand, held earnestly toward you. Take it. Because if you don’t, and

then I die, your conscience might cause you to want to exchange places with me. Here

is my

hand. But even the length of this clunky paraphrase demonstrates how the poem possesses

a condensed mastery of expression. The poem carries some emotional blackmail, which

possibly

gives some insight into Keats’s relationship with Fanny. The final line with that offered hand represents a gesture of hope, desire,

and waiting. Like some great art, it startles by offering what cannot be accepted

or known,

and so we will forever be drawn to it.

This living hand is strikingly intense and personal, and as such a pure lyric in the Romantic sense. It addresses an important subject in Keats’s greatest poetry of this year—timeless or suspended anticipation—such as we find in his odes to a Grecian urn and a nightingale. That is, Keats, characteristically, directs his poem toward a future that may or may not come. Likewise, the poem recalls another Keats poem of 1819 that haunts with risk and uncertainty, and with a warm vision of love countered with and left in cold reality, and with a sorrowful exchange of love: La Belle Dame Sans Merci.

In late 1819, within the contexts of Keats’s failing engagement with Fanny Brawne and his faltering poetic prospects, the figuration of the lingering, offered hand carries, first, the idea of a failed or failing betrothal—the idea of giving one’s hand in marriage, based on handfasting, which Keats would have been aware of; and second, at the same time, the lines conjure his hand as the physical, grasping agent for writing poetry, and here it seems to call out for both revival and recognition, which is fitting given the frail, uncertain state Keats’s poetic life. Were he somehow revived, his blood might, like ink, once more stream. He would write again, had he prospects. Instead, he waits—already, it seems, on the verge of living a posthumous life.

According a friend, Joseph Severn, who sees

Keats during the last week of the month, Keats is well neither in mind nor body.

This

could be bout of anxiety and stress over uncertain future plans, unclear poetic aspirations

(he never seems certain about what to do with his Hyperion project), his very precarious

money

situation, his increasingly unresolved feelings for Fanny Brawne, or even some physical

issues

that have plagued Keats on and off for some time.

*Otho the Great is not staged in the US until June 2016 (in Chicago, produced by Frank Farrell, and running 11-25 June); the play’s title is expanded: The Dark Ages: Otho the Great. Reviews were generally quite good. The play’s world premiere is in London, 26 November 1950, put on by the Premier Theatre Club, St. Martin’s theatre.