11 October 1819: Otho, Fanny Brawne, & Bright Star

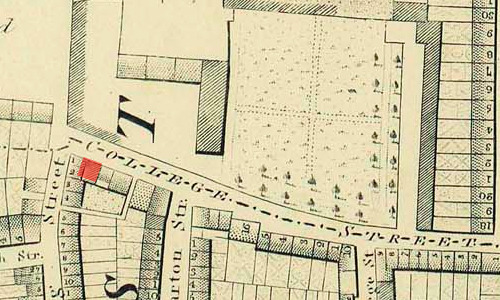

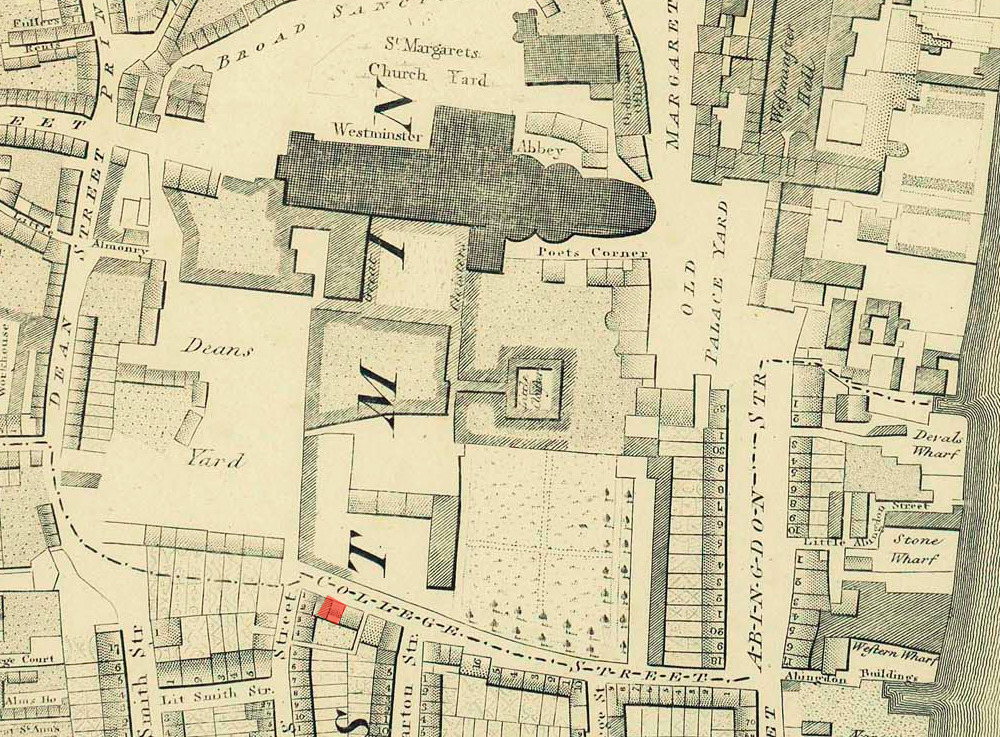

25 College Street, Westminster, London

25 College Street, Westminster: Where, on his own, Keats briefly lives for a short

period

during the middle of October, probably beginning 11 October, after residing in Winchester

since mid-August. How long he stays at College Street is uncertain, but it may have

been as

little as two or three days. He initially wants a couple of inexpensive, quiet rooms

(letters,

1 Oct) where, it seems, he hopes to indulge his desire to read—he says he could not live

without

books (letters, 3 Oct).

Keats considers that neither financial gain nor literary recognition is likely to come from his poetry. He nevertheless has high hopes that a play, co-written mainly over July and August with his great friend Charles Brown, will not just be produced, but also rescue his literary reputation and make them both a decent sum (200 pounds each, he ventures). Brown mainly supplies the plot (generally cumbersome) and Keats supplies the text (minimally decent, with a few splashes of decent dialog). The play—Otho the Great, a kind of overly theatrical and self-conscious take on the Elizabethan family tragedy—is submitted to Drury Lane Theatre in late October. Because of Keats’s non-existing or low reputation, it is submitted in Brown’s name only. The tragedy never gets produced, despite being accepted by Drury Lane in December for staging later in 1820. However, their desire to see it produced quickly causes them to withdraw it from Drury Lane and to try Covent Garden Theatre, where it is later turned down. The play will have to wait 130 years to be staged.* [For more on the play, see 1 July 1819.]

Keats’s plan to rent rooms in Westminster is also motivated by his need to immediately make some kind of living by writing for journals and periodicals. He has lately survived on loans from friends (Brown has been exceedingly generous), since the trickle of money doled out by the manager of the family estate, Richard Abbey, has been on hold, ostensibly for reasons involving legal claims for the family money. (Keats does not seem to know that he is actually entitled to significant money, mainly from the estate of his maternal grandparents.) Clearly something goes wrong with Keats’s Westminster plan: after about 14 October he doesn’t seem to stay there again.

So by the end of the third week in October, Keats is back at his old digs in Wentworth

Place, a double house in Hampstead. Perhaps money is the issue; perhaps (as he himself

suggests) it is the old habit

of the Wentworth Place room that draws him; perhaps, too, it is the chance of being

close to his loved one, Fanny Brawne, that draws him, since along with her widowed

mother her two siblings, she occupies the other half of Wentworth Place.

On 11 October, while still at College Street, Keats writes to Fanny, having just spent a day with her: When shall we pass a

day alone? I have had a thousand kisses, for which with my whole soul I thank love.

Two

days later, in an extraordinary love letter, he confesses he cannot stop thinking

about her:

he writes, I cannot exist without you [ . . . ] You have absorbed me [ . . . ] I could die

for you [ . . . ] I cannot breathe without you.

They are likely formally engaged in

October, though it is kept quiet. Keats’s lingering health issues, lack of finances,

and

personality traits (he is overly jealous and controlling, and his preference is to

live alone)

make it apparent that he is not the best catch for Fanny, not to mention that Keats

is

bothered by Fanny’s outgoing, somewhat coquettish ways, though this may be an unfair

portrayal

of a bright, vibrant young lady, just turned twenty years old. Keats also sees Fanny

a few

more times this month.

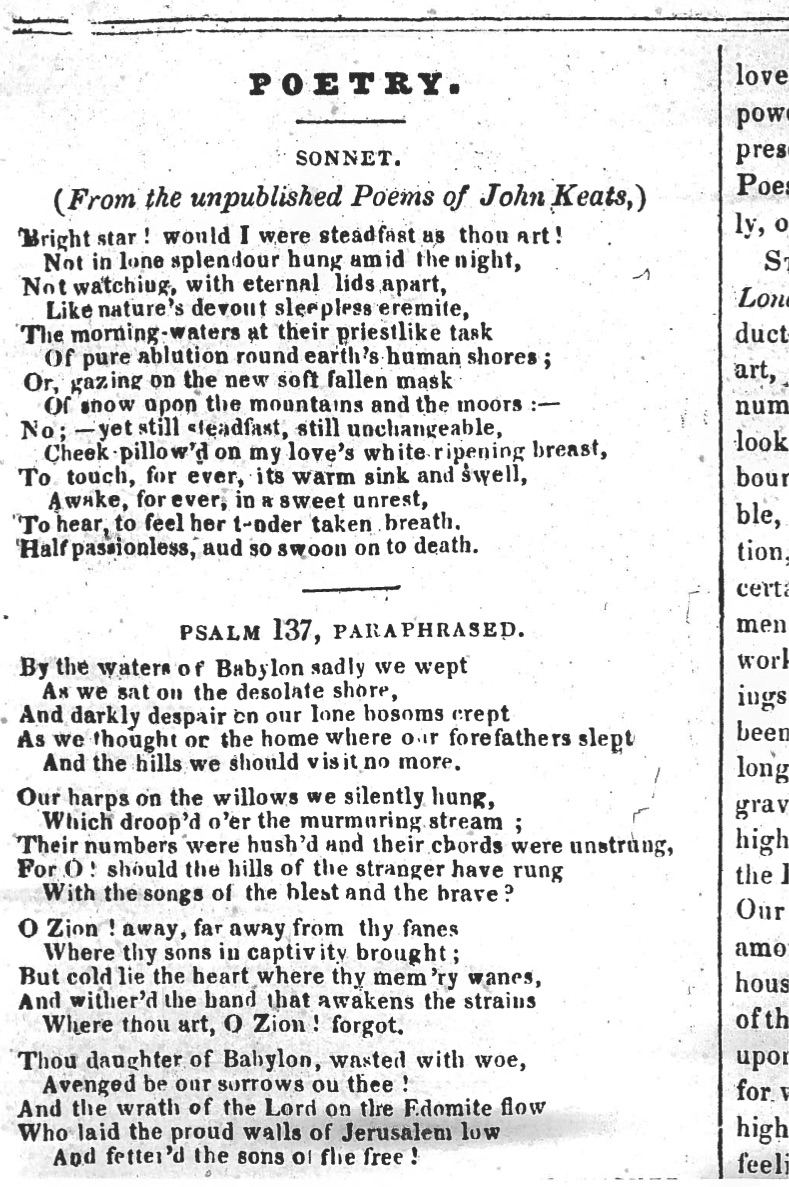

Keats perhaps writes his famous Bright Star sonnet in October, though other times during 1819 are also viable. For example, in July 1819, Keats in a few letters to Fanny uses heavenly imagery in the context of describing his love for her. But suffice it to say that the poem is written in 1819. In its controlled, elegant phrasing and complexity of feeling and thought, and with its deft turn around the notion of steadfastness, the poem approaches Shakespeare’s sonnet-writing talents (in fact, using the form of the Shakespearean sonnet). That the poem is associated with Keats’s deeply conflicted love for Fanny underlines the remarkable poetic composure Keats exhibits in entwining the subjects of love, passion, life, death, and immortality—not to mention his mastery over the sonnet form by subtly innovating upon it. Keats dignifies desire in a way that very few others have, mainly by collapsing the distance between personal, private passion and universal devotion; that is, he manages to capture both the struggle with timeless beauty (as in his Ode on a Grecian Urn) as well as the stilled, living yet eternal promise evoked (as in To Autumn). The distance Keats has moved from his flimsy and largely aimless poetry of just a year or two ago is almost without precedent, where his subject (either overtly or as a subtext) could almost always be reduced to I want to be a poet.

Keats’s shifting, complex, and confused regard for Fanny are also expressed in a few less impressive poems, likely written in or around October—The day is gone, I cry your mercy, What can I do to drive away, and To Fanny. What most strongly joins these poems are Keats’s feelings about and experience of Fanny’s actual physical presence and nature: her shape, waist, warmth, hands, breast, eyes, voice, and lips haunt the poems, regardless of whether his attempted theme is coloured by love, desire, resignation, anxiety, or jealousy—or, more likely, a mix thereof. (There is also a fairly good chance that Keats gives an engagement ring to Fanny just around this time—a fairly affordable garnet set in gold.)

After September 1819, Keats writes little new, substantial poetry. If Bright Star is written in October/November, then it may be his last truly accomplished poem, though his short, startling lyric This living hand might also have been written in October. The period of Keats’s greatest writing is, then, almost exclusively confined to the previous twelve or so months—that is, at this point in October 1919, his greatest progress has been made and his best poetry is behind him. The poems that will go into his third and final collection (titled Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, published June 1820) have already been written, with a slight majority of thirteen poems in the volume written in 1819. Pity that he did not include La Belle Dame and Bright Star and exclude Robin Hood.

*Otho the Great is not staged in the US until June 2016 (in Chicago, produced by Frank Farrell, and running 11-25 June). The play’s title is slightly jigged: The Dark Ages: Otho the Great. Reviews were generally quite good. The play’s actual world premiere is in London, 26 November 1950, put on by the Premier Theatre Club, St. Martin’s theatre.