21 September 1819: Quiet Power, an Odd Sort of Life, Independence via Hyperion, & Uncertainty

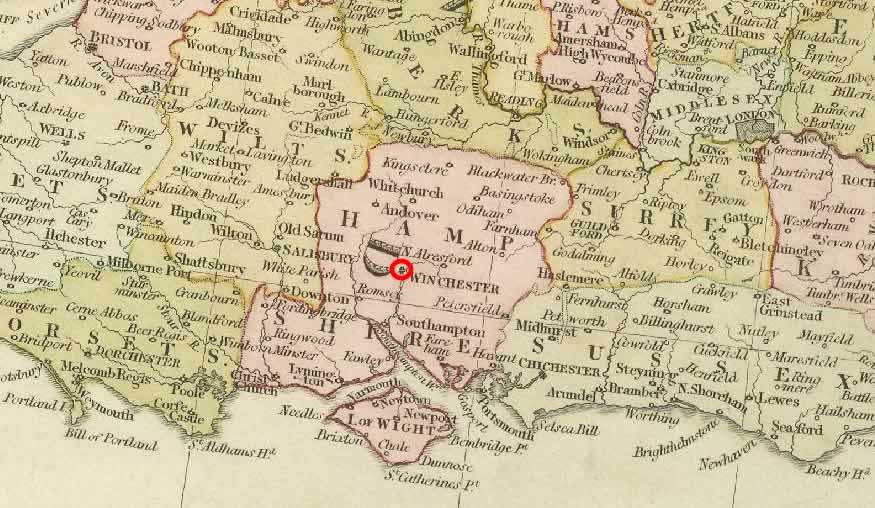

Winchester

Keats, not too far from his twenty-fourth birthday (31 October), has been in Winchester since 12 August with his closest friend Charles Brown, with whom he has been co-writing a play, Otho the Great. They complete it, but despite high hopes—Keats at moments believes it will lift him out of a reputational and monetary hole—the tragedy remains unperformed during their lifetime.

September also sees Keats meet yet again with the manager of his family’s trust, Richard Abbey; the Keats siblings are generally in the

dark about their complete assets, which includes a significant chunk of money held

by the

courts. Keats hopes

to help his brother—George—who, with his wife, has experienced a financial collapse in America. Keats,

too, faces continuing and severe money troubles. Brown has supported him for last

few months,

and Keats is greatly thankful to him for his selflessness and generosity, if not a

little

guilty about it (letters, 22 Sept). Without Brown, Keats says he would have been in

personal distress

(letters, 26 Oct). Keats also receives loans from other friends

early in the month, and he has (unsuccessfully, it seems) asked others to return loans

that he

himself has made when he couldn’t really afford to.

In early September, Keats completes Lamia, a kind of tragic romance imaginatively lifted from Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. He believes it may, with its beautiful

serpent-woman and combination of love, enchantment, and grief, have enough fire in it

to at least have popular appeal and leave readers with some strong sensation (18 Sept,

to the

George Keatses). At the same time, Keats in the poem manages to cover one of his favorite

topics in the poem: the division and difficult conflation of the real, the ideal,

and

illusion. But again, at bottom, Keats hopes to make some money from the poem, despite

his

ambivalence about the very idea of popularity. In fact (and not unnoticed by friends,

particularly his publisher John Taylor), his

attitude toward the public often borders on contempt. This, of course, can happen

when the

larger reading public shows little interest in your work. Keats, too, hopes that his

more

meaningful poetic accomplishment will not be to have conversations with popularity

for the

present, but with the enduring voices of posterity.

Lamia will become the lead

title name in a new volume of poems that Keats is anxious to publish, though the collection

does not appear until June 1820: Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St.

Agnes, and Other Poems. The first two poems that title the volume are not Keats at

his very best. In fact, Keats did not want Isabella published in the

collection at all: he feels it reflects inexperience, simplicity, and weakness; his

editors

will eventually over-rule. He writes to Richard

Woodhouse, his friend and sometimes literary advisor, that he thinks it is the kind

of poem best published after one’s death

(22 Sept). Keats likely recognizes that Isabella,

written about a year-and-a-half earlier, in some ways looks backwards in terms of

his poetic

progress.

The 1820 volume ends with Hyperion: A

Fragment [Book I; Book II; Book III], a poem that Keats

substantially gives up on in April 1819. Keats had taken up the story of the titans

again, in

July, only to give up on it a second time (in what we know as The Fall of Hyperion) this September.

Keats’s desire to make something significant from the Hyperion story does rouse some

very

strong poetry and mark obvious progress—for some, it is his best work. But for Keats,

in

assessing what he has thus far done, he discovers in the work a conflicted engagement

with

John Milton’s style, one that tests his own

poetic judgment and character: as Keats critically cross-examines the poem in a letter

to his

friend and fellow writer John Hamilton Reynolds

on 21 September (and repeated to the George Keatses three days later, in saying he

is on my

guard against Milton

), he expresses his desire to find and use a genuine, English idiom

(which, he believes, Thomas Chatterton

possesses in its purest form), and not one modelled on Greek and Latin inversions and

intonations.

He makes a crucial distinction between poetry that displays its artfulness

too conspicuously, and poetry that originates from authentic feeling and sensation,

and with

more natural style; as he puts it, he worries over the difficult division of the false

beauty proceeding from art

and the true voice of feeling.

And so, he concludes,

I have given up Hyperion.

A possible translation of his comment: I have given up

emulating John Milton and am determined to become John Keats.

We witness here how far Keats has come in his progress over the last year, where the critical subtleties of these self-assessments and the desire for clear, poetic independence are enough for him to put aside a poem into which he has poured much effort. But in the end, even with the changes Keats makes over his two attempts at the poem, he appears conflicted over the aims of epic, allegory, and lyric, and he seems stymied over what in The Fall of Hyperion he might poetically articulate about how to enter and address the human world of suffering through the imagination.

Contending with this distinction between false beauty

and the true voice of

feeling

is, in fact, how Keats manages the final stage of his poetic progress, and how

he has, for even less than a year, been able to rise significantly above his early

poetic

efforts. Perhaps, too, the status associated with completing a long poem (approximating

the

classical, epic narrative) sidetracks the focused conflation of calmness and intensity

that

characterize his greatest and more condensed efforts in the lyric mode, and, in particular,

in

his extraordinary odes of 1819, culminating in the poem that is, perhaps, most assuredly

natural and balanced in its voice—To Autumn. None of this, however, diminishes the remarkable possibilities in

Keats’s abandoned version of fall and suffering in the Hyperion story, and also of

his longest

continuing subject: the role of the poet. One of Keats’s friends, the artist Joseph Severn, will, upon hearing that Keats has

abandoned the poem, strongly encourage him to complete it.

Keats does venture some thoughts on the nature of his poetry, when, on 20 September

to the

George Keatses

, he writes about the difference between himself and

Lord Byron: while Byron writes about what he

sees—I describe what I imagine—Mine is the hardest task.

Keats is quite right in the

first instance, though the issue of the relative difficulty of portraying the two

is of course

questionable, since both the real and the imagined can be equally troubling to engagingly

represent. (The comment no doubt also closets a little jealousy over Bryon’s stunning

popularity.) Keats goes on to write that the nature of his poetry in fact makes some

reviewing

quarters fearful of or shy about actually addressing his poetry, since it might challenge

or

puzzle their tastes and, at most, their beliefs. Keats here acknowledges the political

dimension of contemporary poetic tastes and prejudice, something he knows quite a

bit about,

especially as a result of his public affiliation with Leigh Hunt and his circle in the earlier phase of his writing career. Mind you, the

vast majority of reviews of his poetry written while Keats is alive are neutral or

favorable.

Keats does not see himself as what today we might label a fully transgressive poet

(his

attraction to classical forms and subjects are very clear), but, as mentioned, he

recognizes

the significant political tensions that were underwriting much of the cultural discourse

of

his day. His best poetry, he hopes, transcends politics, tastes, prejudice, and those

tensions. John Scott a deep reader of Keats, and

one who knew as much as anyone about the political poetics of the time (and who, in

fact, died

for them), makes it very clear: in a tough-minded review of Keats’s final collection,

and in

condemning both the right and left for inserting party politics into their criticism,

Scott

writes, Keats is not a political poet

(London Magazine,

Sept. 1820).

Though Keats recognizes that ambition now and then haunts him, on 21 September, in

writing to

the George Keatses

, he musters a self-assessment that looks back upon his

previous disposition and temperament and points to a new one: he recognizes that he

may have

lost some poetic ardour and fire,

but it has been replaced by more thoughtful and

quiet power.

He is more content to read and think,

and not to over-exert himself

with vexing speculations.

He no longer wishes to write verses for the fever they

leave behind. I want to compose without this fever.

This, once more, is a far cry from

early Keats, who, for example, in Sleep and Poetry (written late 1816),

pictures himself earnestly grasping his pen in order to write something, anything—in

order to

feed upon and fully dedicate himself to whatever inspired and sustained his great

precursors;

his only saving grace for such youthful exuberance is that he momentarily sees his

goals as

presumptuous.

What Keats writes on 21 September to Reynolds

shows a moment of reflection on his last few years—the years, that is, he proclaims

and pushes

his poetic ambitions: I have led a very odd sort of life—Here & there—No anchor—I am

glad of it.

Keats seems, at least for the moment, to accept his unsettled, insecure

lifestyle—but one that attunes him to probing and weighing the larger unsteadiness

of life

while always focused on his primary directive: his dedication to and humility toward

the

Principle of Beauty.

*

Keats’s uncertainty about his future is fully apparent in a letter he writes the next

day, 22

September, to another friend and supporter, Charles

Dilke. He attempts to put on a brave face to divert something close to desperation.

Acknowledging his lack of success as a poet (and his mistrust of poetry in general),

and

making it clear that his finances are worn terribly thin, Keats reaches for a jocular

tone; he

writes that he is on the lookout for connections so that he might earn something of

a living

by writing for periodicals, a job he fully despises and mocks for its generally vacant

credibility. Half joking, he writes he is confident he can shine up an article on anything

without much knowledge of the subject, aye like an orange.

But behind the humour lurks

his real situation: he needs to be able to live cheaply, and he needs to earn some

money. And

soon. The letter manages to carry some of the playful Keatsian tone we see at lighter

moments

in his letters, when he is humorously self-conscious of his own thinking, ideas, and

personality. And popping up at one moment is the hyper-sensuous poetic self who has

some

verbal fun pushing up against luxurious excess: to Dilke he pictures himself writing with

one hand, and with the other holding to my Mouth a Nectarine—good God how fine. It

went down

soft, pulpy, slushy, oozy—all its delicious embonpoint melted down my throat like

a large

beatified Strawberry.

September, then, is a month of some abandonments and misgivings and doubt, though,

with that

sense of thoughtful and quiet power,

it also, as mentioned, marks the composition of

his consummate poem—To

Autumn—and therefore, in a way, the end of his progress as we know it; it is his

last truly notable poem before circumstances compromise further advancement. Keats

had no idea

he had saved his best for last.

*Keats notes this not just in few letters (9 April 1818 to Reynolds; February 1820 to Fanny Brawne [I have lov’d the principle of beauty in all things

], but of

course it emerges as a quiet truism in the famous opening line of Endymion, as the lasting property that lifts us from and counters our all-too-human

darkness: A thing of beauty is a joy forever.