11 September 1819: Keatsiana

: Fine Air, Lamia Completed,

Downright Perplexities

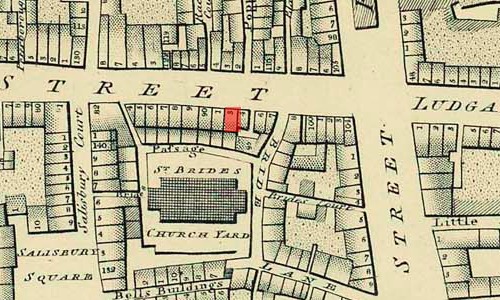

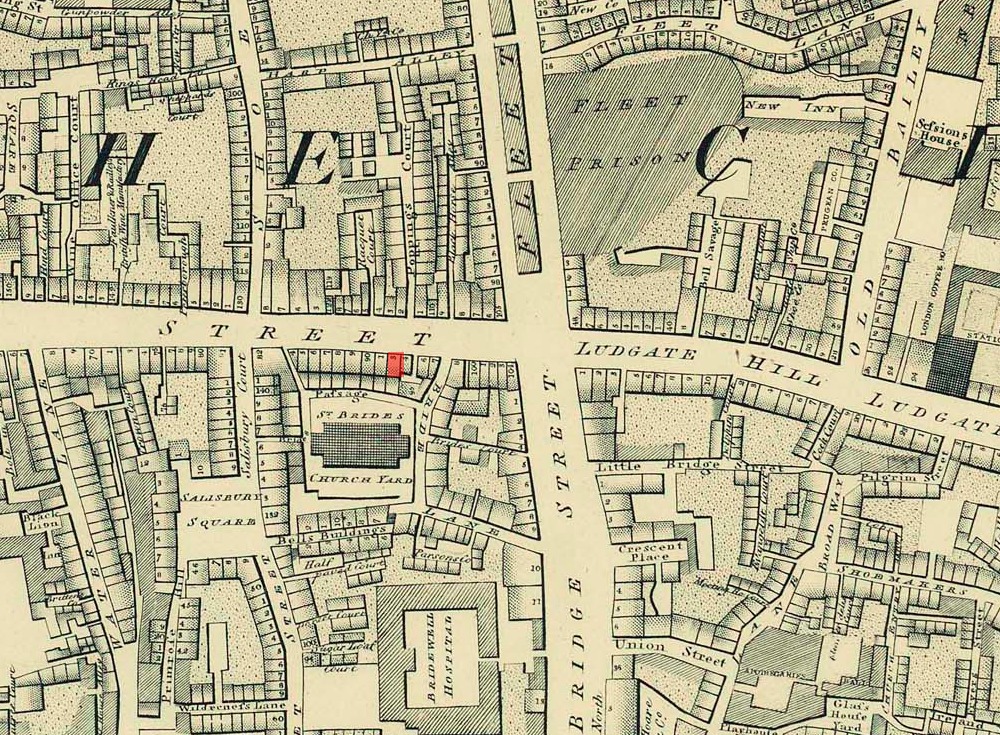

93 Fleet Street, London

93 Fleet Street houses the offices of [John] Taylor & [James] Hessey, publishers/booksellers, and publisher of Keats’s Endymion (1818) and, to come, the remarkable 1920 collection; and where, on 11 September 1819, travelling from Winchester, Keats drops by (unexpectedly) and sees Hessey and Richard Woodhouse, advisor to the publishers, as well as being Keats’s close friend and supporter. Hessey, too, is a friend and great believer in Keats’s talents. Keats is back in Winchester on the 15th.

Keats, aged twenty-three, lives in Winchester from about the end of the second week

of August

with his great friend Charles Brown, with whom he

has been diligently co-writing a play, Otho the Great. Keats

describes his role in the project as Midwife to his [Brown’s] plot

(letters, 5 Sept).

Despite high hopes—and the grave need for Keats to make some money—the play never

gets

produced in their lifetime. The warmer weather and favorable ambiance of Winchester

seems to

improve Keats’s health. And autumn suits his sensibilities: How beautiful the season is

now—How fine the air

(letters, 21 Sept). The season and the place in fact facilitate the

composition of perhaps Keats’s greatest poem, To Autumn, written 19 September.

Keats travels to London mainly to meet with the sometimes difficult manager of his

family’s

complex estate, Richard Abbey, and Abbey invites

Keats for an evening tea on the 11th. Family assets seem temporarily frozen by a possible

legal suit (or claim) against the estate. Keats’s mission is to help his brother—George—who has had a financial collapse in America:

George’s investment in a venture with John James Audubon, the famous naturalist but

also, it

seems, callow capitalist, has more or less bankrupted George, and George hopes to

acquire

funds from the family estate. (A significant financial crisis in the US at the time,

the

so-called Panic of 1819,

is part of the backdrop to George’s difficulties; Keats is

fully aware of the situation, and comments on it in a letter to his sister Fanny on 26 October: he mentions the general depression of trade

in the whole province of Kentucky and indeed all America.

) Abbey commits to help clear

things up.

Keats, too, has lately suffered financially. Brown has supported him for the last few months, and this continues into October;

without Brown, Keats writes, I should have been in, perhaps,personal distress

(letters,

?26 Oct 1819). In early September, Keats receives funds from other friends (including

money

via Taylor and Hessey); he is basically living month-to-month. He returns to Winchester

15

September. Keats seems unaware that he is entitled to fairly significant funds from

the family

money, and a picture of Keats’s family finances will not be clear or settled until

after Keats

passes away. While in London, Keats also manages to meet with his younger sister,

as well as

see some friends and take in a little theatre.

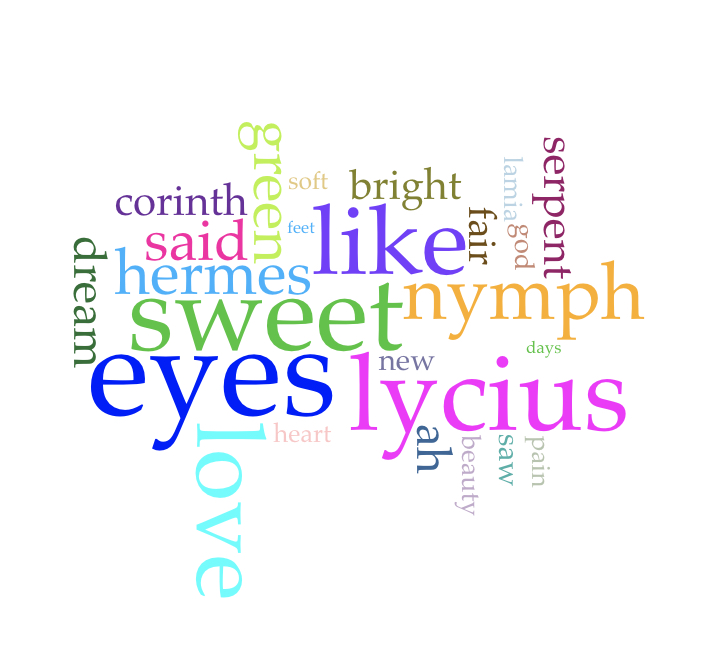

Keats has just completed

Lamia, a poem he hopes will have some public appeal and encourage sales of his

foreseeable volume with publishers Taylor &

Hessey. Keats believes there is fire in

it,

and that it offers the kind of sensation

that the public wants (letters, 18

Sept). Keats, however, misses the mark a little with the poem, perhaps because he

attempts to

gauge the public’s taste rather than represent his own poetic strengths. Although

the poem’s

plot (lifted from Robert Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy)

overflows with topics from which Keats has recently poetically profited— uncertainty

and

undetermined truths, illusion/reality, mortality/immortality, mutability/permanence,

human

vanity/the ideal, love/loss, an unsympathetic world—the story of a beautiful serpent-woman’s

love for a mortal does not nearly rise to the level of Keats’s very best poetry—that

is, to

poetry written earlier in the year. What has matured, though, is Keats’s natural poetic

tendency to reflect conflicting and contrasting sensations and thoughts without affected

poeticisms and stylistic overreaching, and with a tempered, unobtrusive voice.

Lamia, however, with its

narrative turns and twists, does not continuously or consistently reflect those topics

or this

style in penetrating or inspired ways. Perhaps the narrative mode (as opposed to the

lyric

mode) does not stir Keats’s greatest strengths as much as dilute them. Despite these

weaknesses, Woodhouse, who is probably the

first to see something close to a fair copy of Lamia, is impressed enough to write to Taylor and to retell the whole plot. Keats, Woodhouse reports, has a fine feeling when

& where he may use poetical licences with effect

(19 Sept). This is an interesting

comment from someone who knows Keats and Keats’s work very well, but he may have pointed

to an

aspect of the poem’s deficiency: it employs a little too much poetical licences,

and

one of Keats’s declared goals for his best poetry is for it not to display, as it

were, poetic

artifice or excess. At best, we could extend the critical sophistication of Lamia by suggesting that, as

drama of idealization, it offers us a kind of allegory of false interpretation. At

the same

time, and on a more plotful level, the poem offers a kind of critique of love (as

a form of

fantasy or delusion) that pits it against the cold, hard, real world. (Keats also

works this

storyline into both The

Eve of St Agnes and La Belle Dame sans Merci.) Now,

these aren’t bad ways to look at the poem, except that Keats does not represent this

drama or

allegory or plot in a superior way. But at least, he hopes, the public might buy into

(literally) the poem’s passions and sensations. Again, at this point, he very much

needs the

money and some sense of success.

Keats hopes to have The Eve of St Agnes and Lamia published by Taylor & Hessey as soon as possible, along with some of his odes, though revisions to The Eve of St Agnes are an issue: a relatively explicit description of the amorous encounter between Madeline and Porphyro is the problem. Woodhouse believes it makes the poem unfit for female readers; part of Keats’s response is that he writes for male readers only, though this may be tainted by a little defensive posturing.

On 19 September, Woodhouse (Keats sees much

of him during the brief London trip) reports to Taylor that Keats thinks little of Isabella; or, The Pot of

Basil (written in early 1818); mawkish,

Keats calls it. Woodhouse brings

up the poem in the context of what might go into Keats’s next collection. Woodhouse,

however,

disagrees with Keats’s assessment; he believes that the poem does not contain sugar &

butter sentiment, that cloys and disgusts.

Woodhouse also comes up with a very useful

insight about the nature of Keats’s work: as opposed to hearing Keats’s poetry, his poetry

really must be studied to be properly appreciated.

Indeed. And Woodhouse is probably the

first to utter a word with respect to the subject he finds himself writing about at

length:

Keatsiana.

On this trip to London, and before returning to Winchester on 15 September, Keats

sees his

younger sister, Fanny. Noticeably, he does not see

Fanny Brawne, his intended, whom he has

probably not seen for more than about two months. Although he still confesses intense

and

unceasing love for her, not seeing her might be tied to anxieties about his finances,

his

health and state of mind, and his desire to remain independent. Keats confesses to

her that

seeing her would create downright perplexities

that would destroy the half

comfortable sullenness I enjoy at present,

and he adds that he has been trying to

wean

himself from her: I cannot bear the pain of being happy

—seeing her, he

writes, would be like venturing into a fire

(letters, 13 Sept). Poor Keats.