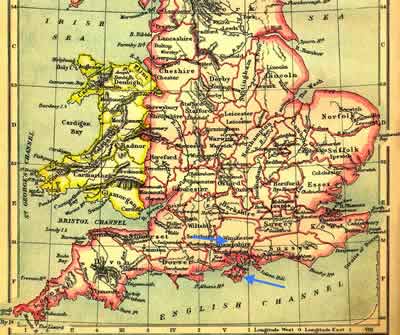

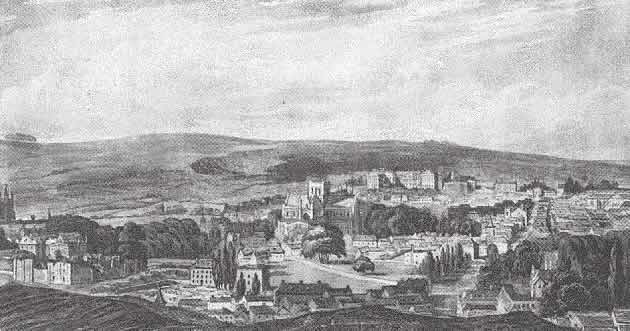

19 September 1819: Winchester: Chaste Weather, On Guard Against Milton, To Autumn at Ease with Itself, & the Unegotistical Sublime

Winchester

Keats, aged twenty-three, has been staying in Winchester since the second week of August with his very close friend Charles Brown, with whom he has been co-writing a play, Otho the Great. Their primary motivation, especially for Keats, is money, though for a moment or two Keats has inflated thoughts about shaking up contemporary drama. Keats and Brown will miss an opportunity to have the play produced, in part because of their impatience to get the play on the stage. Otho the Great remains unperformed during their lifetime—indeed, during their century. But then there’s the surroundings: the warmer weather and favorable ambiance of Winchester seems to improve Keats’s health and spirits—and to inspire him.

On 10 September, Keats goes to London to meet with the manager of his family’s complex estate, Richard Abbey, and he will have tea with Abbey on the 11th. Family money seems frozen with an uncertain (but unlikely) Chancery suit; Abbey, though, in some ways, seems to keep the Keats siblings in the dark about their assets, which in fact are, unbeknownst to them, fairly considerable and held by the court. Keats sincerely hopes to help his brother—George—who has had a financial collapse in America; Keats feels George may have been fleeced and deceived in his business deals (letters, 21 Sept). George had invested all his money on a shipping boat that travels the main river routes, but the boat sunk. Keats, too, has lately suffered financially; Brown has supported him for the last few months. In early September, Keats receives loans from other friends, and he has just earlier attempted to call in loans that he himself has made. Keats returns to Winchester 15 September.

September sees Keats once more give up on the epic Hyperion story. The attempt (in the earlier guise of Hyperion and now what we know as The Fall of Hyperion) brings forth much strong poetry and represents clear progress in avoiding affected sentimentality for a more classical, tempered, sincere vision; but, as he attempts to explain to his friend and fellow poet John Hamilton Reynolds, with its uncertain engagement with John Milton’s accomplishment, story, and style, it seems to test his patience as well as aspects of his poetic judgment and his own poetical character.

As Keats critically cross-examines what he is achieving with The Fall

of Hyperion, the distinction between purposefully artful poetry and poetry that

originates from feeling and sensation seems to cause him to give up

on it (letters, 21

Sept). As a vague reworking of Milton’s Paradise Lost, the overly abstract and indeterminate allegory—now

with an added kind of dream-vision and a clear questioning of the role of the poet

in

addressing suffering—might have been another reason for Keats to abandon it. Keats

desires to

find a form and voice—and subject—that allows him explore what he calls the true voice of

feeling

rather than artful

Miltonic expression, which, at least in his own hand,

might end up as the false beauty proceeding from art

(21 Sept). Keats in a way suggests

to Reynolds that he cannot fully figure out

when he sounds too much like Milton and not enough like himself, and this, too, may

have been

one aspect of his giving-up on the poem. As Keats mentions in a letter to George and his wife,

he needs to be on guard against Milton

and Milton’s style of art and devote myself

to another sensation

(letters, 24 Sept). That Keats can muster such critical

self-understanding underlines how far his poetic sense—and sense of his own poetic

originality—has developed. And we have to keep in mind that—as we see in Keats’s marginalia

in

his copy of Paradise Lost—Keats is nonetheless in awe of what he sees (in his own

terms) as Milton’s immensity, grandeur, and magnitude, as well as in the blind poet’s

unyielding pursuit of the imagination’s capabilities; as Keats writes in his marginalia,

Milton is godlike in the sublime pathetic.

In early September, Keats completes Lamia, a poem with, he hopes, some popular appeal. Keats, however, has

recently expressed ambivalence about popularity: on one hand, he is confident he can

achieve

it; on the other, he worries over the poisonous suffrage of a public

(letters, 24 Aug).

Lamia is to be included in a new collection of poems he is anxious to publish, and Lamia becomes the lead title for the volume, eventually published by Taylor & Hessey in June 1820: Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems. Interestingly, the first two poems that title the otherwise exceptional volume are not Keats quite at his very best (or, at least, what we might call his most Keatsian; in fact, Keats did not want his Boccaccio-inspired Isabella published at all, since it was, in his opinion, simple, immature, and weak (22 Sept, to Woodhouse). And Hyperion, as a fragment poem that ends the volume, he likewise did not want published, but his editors nonetheless included it, since they found it exceptional; Keats was not happy. The poetry that actually caps Keats’s poetic progress are five odes that appear in the volume, along with The Eve of St. Agnes, which exhibits Keats’s gift for evoking a rich and sensual ambiance while, in narrative form, offering an allegory about the dangers of imagination (or superstition? love? temptation? dreaming?) in the face of cold, stark reality.

On 19 September, Keats composes his last great poem, To Autumn. Two days later, in a letter to his good friend and fellow writer, John Hamilton Reynolds , Keats describes the conditions and inspiration for the poem:

How beautiful the season is now—How fine the air. A temperate sharpness about it.

Really, without joking, chaste weather—Dian skies—I never like stubble fields so much

as

now—Aye better than the chilly green of the spring. Somehow a stubble plain looks

warm—in

the same way that some pictures look warm—this struck me so much in my Sunday’s walk

that

I composed upon it. I hope you are better employed than in gaping at the

weather.

Stubble-plainsand

the fume of poppiesaround Winchester (and in Keats’s poem), the South Downs Way (click to enlarge)

Integral to the poem’s composed temper is how this description of autumn merges with

a more

meaningful impression within the poem. The series of dashes suggests how much the

flowing,

interconnected senses struck

him. Somewhat paradoxically, what is remarkable is how he

is excited by the calmness—the beauty, the fineness, the purity, the texture, the

warmth. The

idea of chaste weather

takes us further into what Keats conveys in the poem, both in

what he describes and in how he describes it. This is affirmed by his idea of Dian

skies

—once more, a sense of the unsullied and pure, and without any necessary

embellishment. Keats emphasizes to Reynolds

that he is very serious about his sensations—Really, without joking . . .

. In short,

and in terms that Keats would use, there is something to be intense upon.

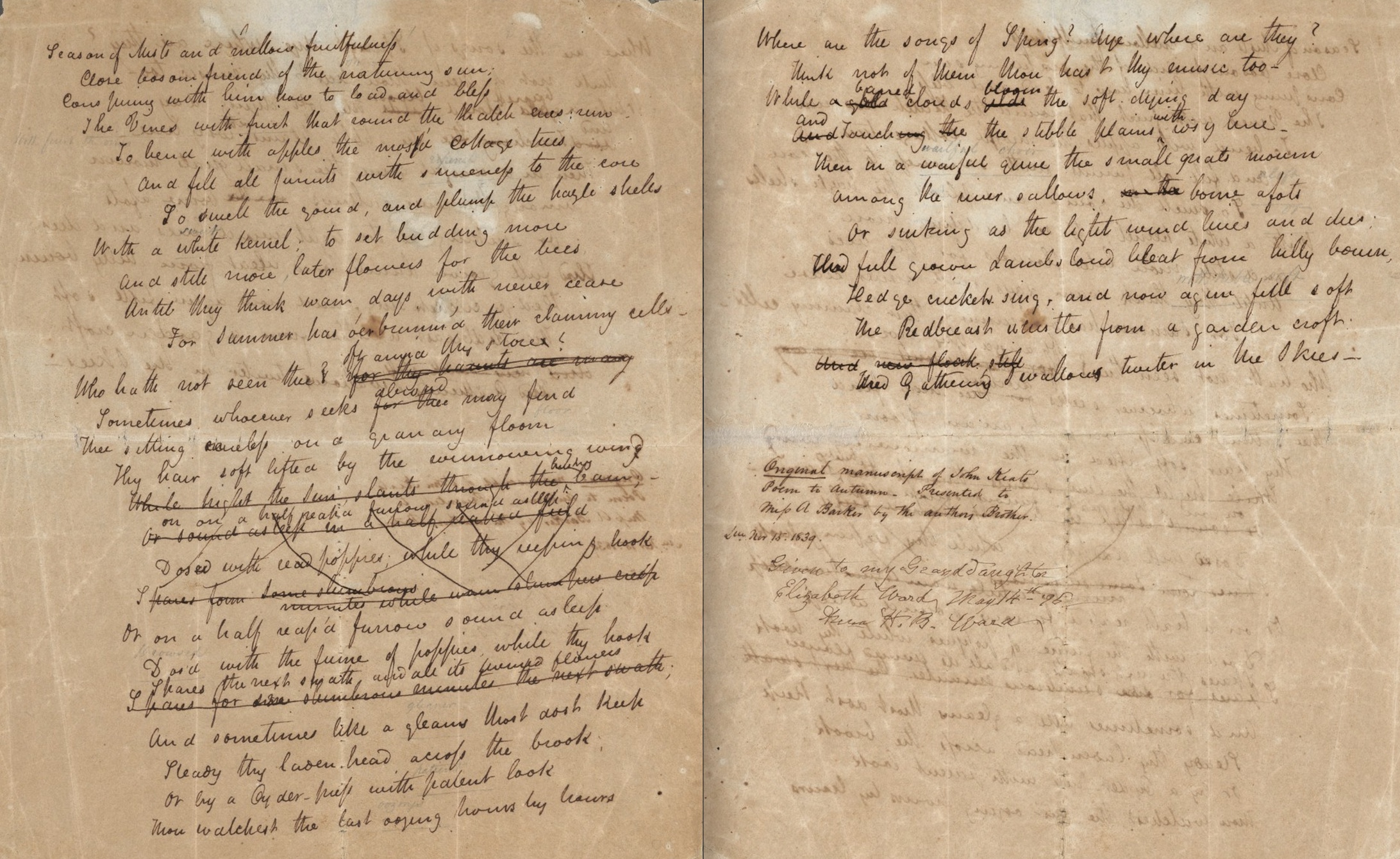

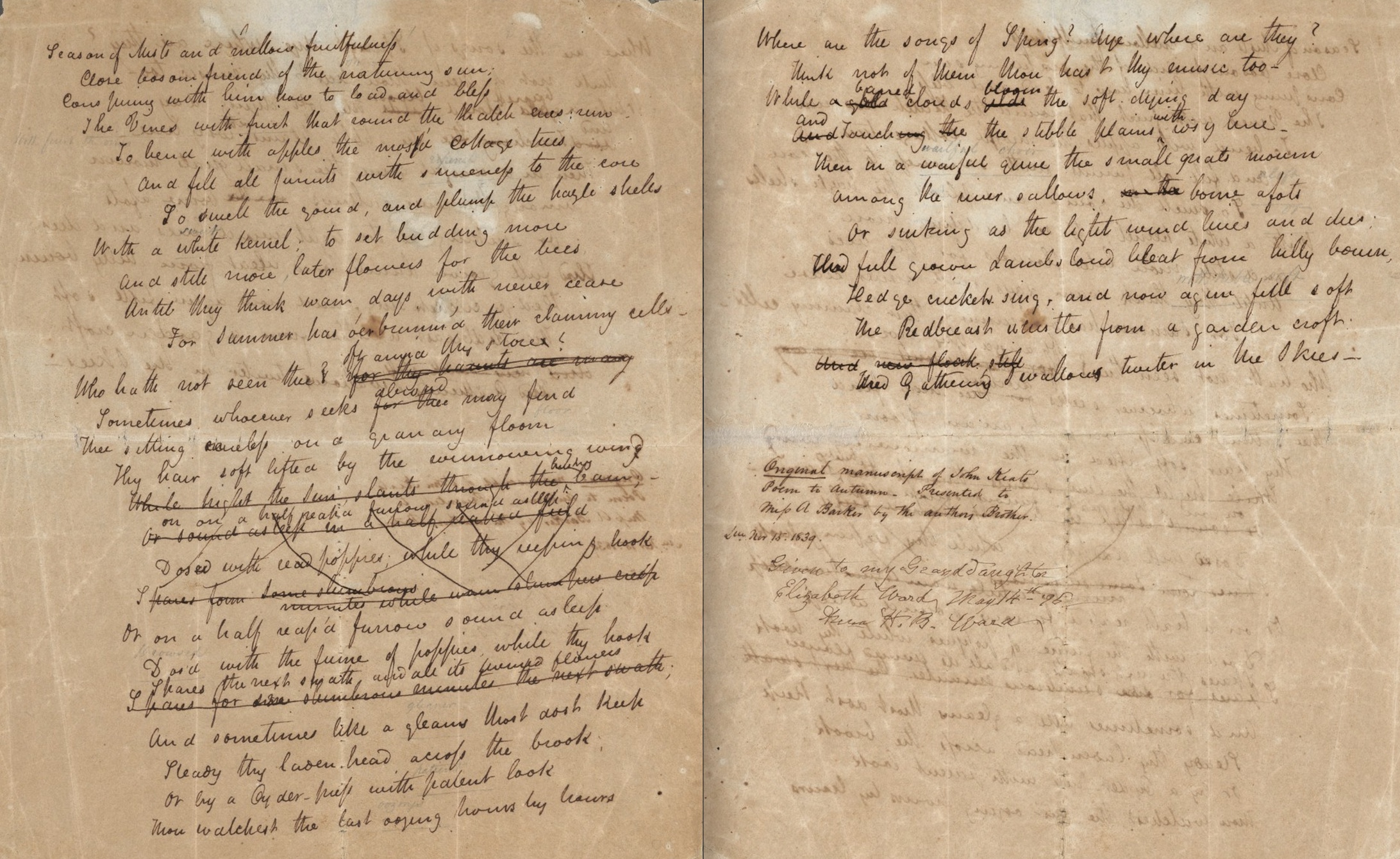

Season of mists . . .(click to enlarge)

From this, we can go to the poem. In To Autumn, Keats perfects his

ability—particularly through his easeful, confident, and settled tone—to find stillness

and

depth in holding time and sensation still, yet also intimating movement and life’s

connected

process. The senses of completeness and process and change are profitably

indistinguishable—complete incompleteness, we might call it, or stilled process, or

perhaps

even continuous stillness. In this way, the poem is also an allegory of poetry’s own

possible

perfection—or at least the kind of verse Keats has worked to achieve: poetry that

conveys

naturalness within complementing form; poetry that balances intensity with unobtrusiveness;

and poetry that represents ripeness while being itself perfectly, poetically ripe.

Mutability

is held immutable though moving, and this is part of the complex impulse behind his

other odes

of 1819, particularly those on the Grecian urn and the nightingale. Keats at one moment

in his

poetics describes how poetry must be content, that the imagery should evolve naturally

and be

set soberly

; it requires fine excess

(letters, 27 Feb 1818); and here, in

To Autumn, that

excess—in the senses and in sensation, in touching, seeing, hearing, in that swelling,

plumping, budding, and over-brimming—indeed finely pushes up against excess, without

exceeding

it. It captures a moment of fullness, ripeness, and gathering, but all is tempered

by

steadiness and patience and harmony. It is, once more, the immutable within the mutable.

That

a sense of death’s settled sadness ends the poem—in the soft-dying day,

in a wailful,

mourning choir, in the light wind [that] lives or dies

—gives us the larger thematics of

loss and acceptance that Keats has been working toward for a few years. It is a point

where,

so to speak, poetry is greater than itself, making it great poetry.

And stylistically: the syntax is natural, direct, and generally uncluttered; the form ingeniously massages the sonnet; and the word choice is anything but eccentric. The poem is remarkably at ease with itself, and subtly employs all the senses to connect with and reflect Autumn’s tranquil but rich promise.

Thus To Autumn

approaches the depth of what Keats sees William

Wordsworth achieve in, arguably, his two greatest poems, Tintern Abbey and the Intimations Ode: acceptance

trumps striving; life is seen into; the eye looks with sober colouring

upon

the day’s end (Intimations Ode, 200); and recognition that the

external landscape is connected to something deeper and longer lasting than the ostensible

moment of being in and just looking at that landscape. In short, this early work by

Wordsworth

is a marker and measurement of Keats’s accomplishment, and Keats fully knows it.

It may be coincidence, but Keats’s poem also recalls the momentary sentiment of Keats’s

closest contemporary young poet, Percy Shelley,

who, in his Hymn to Intellectual Beauty (published early 1817

and republished in Shelley’s 1819 Rosalind and Helen

collection) writes there is a harmony / In autumn, and a lustre in its sky

(and

Shelley, too, has one eye on Wordsworth).

But Keats’s remarkable achievement—built upon his poetic progress up until this point;

upon

his poetics; and upon his deliberate study of Shakespeare, Milton (most obviously

Il Penseroso), Wordsworth, Coleridge (in particular, Frost at

Midnight), and (at least in spirit) Chatterton—is that To Autumn is not channeled through or

negotiated by a speaker’s subjectivity as a dominating or intruding presence. Intensity

is

entirely controlled, despite, once more, those forms of excess that autumn offers

or

represents; surplus is held in restraint, and this holding is not just of the real-world

oozing fruit, but for the expression of the capably imaginative poet. The only very

slight

leakage takes place in the speaker’s rhetorically repeated question, Where are the songs of

spring? Ah, where are they?

(23). Little, then, seems to depend upon a speaker’s

presence or experience, except the assurance of an extraordinarily subtle empathy

with

stillness, fulfillment, and death. It is the unegotistical sublime, and as a modern

lyric ode,

it is exemplary at very least, and at best perhaps matchless. When Keats writes that

he has

lost his earlier poetic ardour and fire

for a more thoughtful and quiet power,

To Autumn represents

this change and progress (21 Sept, to the George Keatses).

Importantly, in light of Keats’s turn away from the language and artifice of Milton, Keats this month expresses his attraction to the language—to unforced English idiom—of Thomas Chatterton, which Keats feels is pure, uncorrupted, and genuine; moreover, Keats says that he associates Chatterton with autumn. We recall that Keats in fact co-dedicates his Endymion volume to Chatterton, declaring him to be the most English of poets—after Shakespeare, that is. This association answers something of the poetic ease we encounter in To Autumn.

Hyper-contextualization of Keats’s work sometimes functions to dip the poem too deeply into politics, economics, or subversive government practices; and then, in the other direction, there are readings that suggest, for example, that the poem in part enacts Keats’s apparent preoccupation with the maternal breast.* These top-down readings perhaps miss or misread the high achievement of lyrical practice and larger thematics that Keats gets right in the poem’s originality, despite pictures of autumnal repose being a fairly common trope in both poetry and painting. We should fully trust Keats when he enthusiastically tells Reynolds (above) that what strikes him to compose upon is the complex beauty of, and his immersion into, the tranquil profundity of the scene; the fine, temperate sharpness of the air; the warmth and the pureness that he perceives and feels; the restrained potency of what the season represents—all of which takes us to Keats’s final subjects: time, nature, and poetic self-possession in the face of accepted, human tensions. And it is very clear, as in Keats’s best poetry, that settled in-betweenness is the poetic state that Keats arrives at or attempts to represent—in this case, the state that exists between silence and sound, maturation and decline, collecting and release, suspension and movement, stillness and process, and, of course, life and death. That state exists outside of history, and Keats’s poetics and other best poetry make this clear, whether that state is represented by an urn, a nightingale, or a forever-lingering knight on a cold hillside. Keats’s own words, then, are the real introduction to the poem. We might assume that Keats knows more about his poem than we ever can.

Keats will transcribe a copy of To Autumn in a letter to Woodhouse, 21 September, along with some lines from The Fall of Hyperion, including the powerful, assured opening of the poem, which teasingly articulates the role of poetry and the poet. Keats’s heavy revisions to the poem (and in particular, to the second stanza) point to its hard-earned elegance and covert simplicity.

To Autumn,Houghton Library, Harvard University (MS Keats 2.27). Click to expand.

*The challenging idea that the poem expresses Keats’s retreat to the maternal breast

comes

from Richard Marggraf Turley’s ’Full-grown lambs’: Immaturity and To Autumn

(in Romanticism on the Net, no. 28, November 2002).