1 May 1819: The Great Odes, Amulets Against Ennui, & the Mystery of Greatness

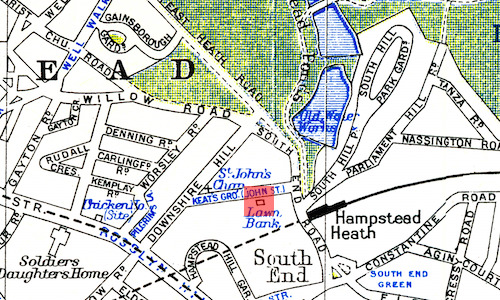

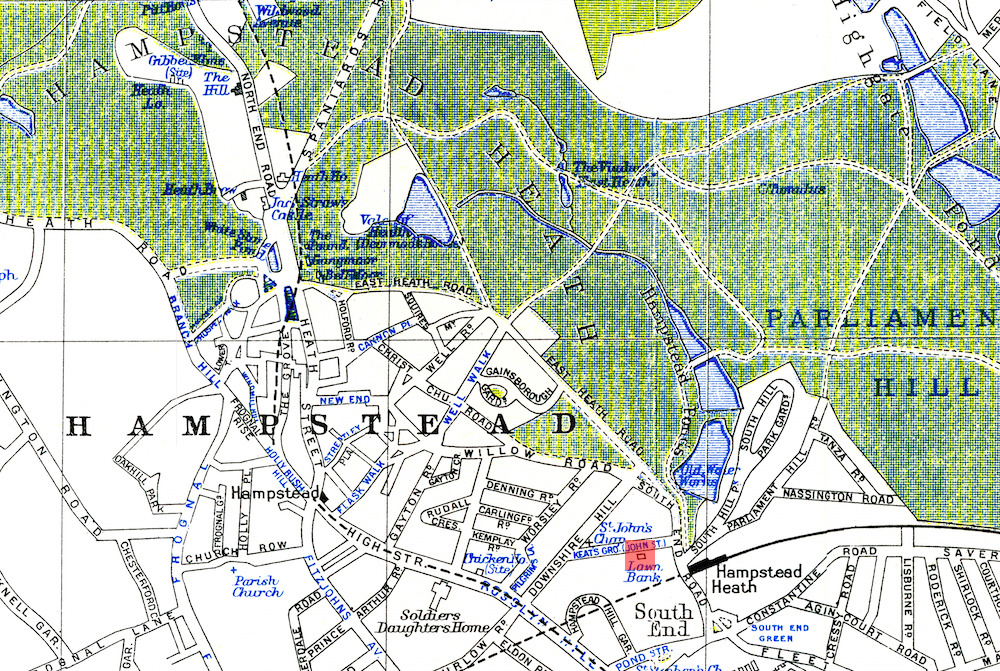

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Compared to April, in which Keats, aged 23, does much socializing (wining, dining, partying, visiting, entertaining, card-playing), some poetic simmering, a little philosophical speculation, and some useful composition—most notably La Belle Dame and a couple of sonnets that put more immature conceptions of fame behind him—May 1819 is considerably less occupied. Or so it seems.

How Keats begins the month: In an upbeat letter to his sister—likely written 1 May—Keats jauntily describes what it

takes to enjoy the day: O there is nothing like fine weather, and health, and Books, and a

fine country, and a contented Mind, and Diligent-habit of reading and thinking, and

an

amulet against the ennui

—not to mention (he continues) cooled claret, cakes, an outdoor

bath, a strawberry bed to pray in, a rambling horse to ride on, and people of all

sorts to

chat, spar, or argue with, as well as a few to laugh at. With spirits high, he ends

the letter

with twenty-nine lines of silly doggerel, Two or Three Posies. Keats in early

May reaches a moment where he believes that existing sonnet forms are lacking: he

thinks

seriously about discovering a better sonnet stanza than we have

(letters, 3 May). This

we something to consider; it is a point of much critical confidence and the result

of much

study; and we will see something of this innovation in the stanza forms of the so-called

great

odes that come shortly.

How Keats ends the month: On 31 May, Keats writes to one of the Jeffery sisters

(Sarah), whom Keats and his brothers likely meet in Teignmouth in March/April 1818.

A little

surprisingly (even to himself), Keats reveals quite a bit: he feels he has two life

choices—two Poisons

—from which to choose: the one is voyaging to and from India

for a few years; the other is leading a fevrous [feverous?] life alone with Poetry—The

latter will suit me best—for I cannot resolve to give up my Studies [. . .] Yes, I

would

rather conquer my indolence and strain my nerves at some grand Poem—than be in a

dunderheaded indiaman.

Keats resolves that he must now muster energies to fight

in his dealings with the

world,

having been largely careless of the world as a fly.

What is also worth

noting once more is how much Keats pairs his poetic success with very deliberate

Studies.

For Keats, producing great poetry may result from the more mysterious

workings of the imagination, but it is bolstered by and connected to acquired knowledge—and

working hard at it.

Toward the end of the 31 May letter, Keats quotes a few lines from the penultimate

stanza of

William Wordsworth’s Intimations Ode about

how (in the surrounding context of the quoted lines), despite loss, emotional and

philosophical strength will be found in what remains behind

(line 185).

Given Keats’s own situation—with the early death of his parents and the recent death

of his younger brother Tom, with his other younger brother in America, with his sister

protected from him by the family guardian, with acute financial uncertainty, with

doubts about his future as poet, and with his own lingering serious health issues

that could not have been lost upon him—the larger idea in these lines means something

important for Keats, and they call up the concluding phrase from Wordsworth’s ode:

some thoughts are too deep for tears.

The settled depth of Wordsworth’s concluding image is not lost upon Keats, for acceptance

of the mystery that conjoins joy and loss, suffering and acceptance, mutability and

permanence, works itself into the thematics of his best work.

Wordsworth, then, is a looming, ambivalent, contemporary presence in Keats’s poetic development; and, as mentioned, he always seems to make some kind of return in Keats’s most considered thoughts: part of Wordsworth’s poetic accomplishment is to shape and restore beauty, meaning, and truth in the face of necessarily larger sorrows and grief. Keats has for some time felt that addressing these topics and achieving this depth is necessary for his own poetic progress. That is, this is the territory into which he needs to venture.

So what did Keats do during this seemingly quiet month?

Between these two letters of 1 May and 31 May, Keats fairly likely composes some of the most remarkable lyric poetry in the English language: his ode on the nightingale, and possibly odes on a Grecian urn and melancholy—all of which follow quickly upon his Ode to Psyche (likely written in very late April—see 30 April), and his Ode on Indolence (likely written in April or May).

In a way, then, May 1819, or more generally the spring of 1819, is a great mystery—or

a

mystery of greatness: its resulting poetry is the major reason why we continue to

search,

probe, chronicle, and be inspired by Keats’s life, thought, and work. Yet, once more,

in terms

of what we know about him during May and its surrounding weeks, there is hardly anything

beyond a couple of short letters and a few short letter-notes to go on—little to provide

insight at the very time he takes his most pronounced leap to greatness in early 1819.

Keats

says almost nothing about his most influential poetry. Then again, the poetry speaks

for

itself. And, if we take him at his word, a few months earlier, in February, while

he is

finding composition difficult, he anticipates the end of winter as motivation for

his writing:

as he declares, I must wait for the spring to rouse me up a little

(letters, 14 Feb).

And indeed, it is quite a rousing!*

But what we do know it this: at the very end of April, Keats hopes to be in a more

peaceable and healthy state

that will encourage composition (letters, 30 April). And

now, formed behind and perhaps leading to this state,

he can fully and at last apply a

brilliant and developed poetics. These poetics begin to vaguely form in the fall of

1816, as

he composes more and more poetry and declares it as his vocation. The foundation for

these

poetics is Keats’s genuine preoccupation with the poetic process itself: What goes

into making

the poetical character? What goes into composing consummate, enduring poetry? In what

forms

can he best express himself most naturally? These questions take Keats about three

years to

answer—first in his poetics, and then, and only then, in the poetry itself.

Although Keats’s interest in poetry begins with his schooling at John Clarke’s academy in Enfield (beginning 1803), to be

subsequently focused and inspired by Clarke’s son, Charles Cowden Clarke,** his thoughts about poetry rapidly evolve from (and then

away from) the poet, critic, and celebrity journalist, Leigh Hunt, who, in 1816, first publishes and befriends Keats. From that point on,

and within a year, and in spite of what turns out to be Hunt’s detaining influence,

Keats’s

progress is nurtured and challenged by a rapidly expanding intellectual and social

network,

and his poetics begin to articulate his desire for poetry that expresses a deliberate

but

natural complexity and depth, formed by constrained intensity—and all motivated by

what is

more difficult to account for in Keats’s makeup: the yearning Passion I have for the

beautiful

(24 Oct, to the George Keatses).

These key elements and circumstances underwrite much of Keats’s progress, but poetically mastering or taking advantage of these cannot happen without Keats’s oft-stated determination to study great work—poetry, drama, and art, as well as some critical and philosophical work. Thus we have the remarkable story of a young man with excessive, complex feelings and a brilliant, probing intellect, who turns his life’s attention to a particular mode of expression. These qualities are recognized by Keats himself. He is certain of his own potential, of what he wants to do, of his difference, and how he needs to do it. Keats thus strives to find a voice and forms that can capture, control, and poetically represent that excess in thought, sensation, and imagination so that it might see him beyond his own—and our—mortality. That is why tethering Keats to a particularized history is interesting, but recognizing his declared desire to artistically exceed history tethers him to all of us—and to enduring greatness. When he writes odes to an urn, a nightingale, the mystery of an emotion, and autumn, it is not the ideology of his time that he attempts to invoke or address. He is, rather, exploring the urn’s evocative yet quiet defiance of time; the nightingale’s immortal song; the mystery of sorrow; and how autumn’s stilled yet never-ceasing sounds and colours represent forms of serenity that look beyond and through the cycle of life and death—so that his poems, too, will join their timelessness by uniquely representing them in the highest form of human expression he knows of—poetry.

* Elsewhere I call this mystery of Keats’s greatness the Junkets factor.

See factor #12 here. The name Junkets

was probably given to

him by Leigh Hunt as a play on the sound of Keats’s full name.

**In his September 1816 poem to Clarke, Keats

writes, you first taught me all the sweets of song

(53).