3 May 1819: The Odes: Mastery & Maturation via Controlled Intensity & Capable Form

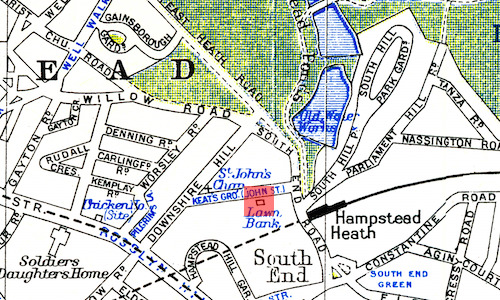

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Given what we know, May seems relatively slow, at least socially: Keats sees his younger

sister, Fanny, a few times, though he worries

about her strength and relationship with her guardians; he is excited and relieved

to receive

a letter from his brother George and his wife,

Georgiana, who emigrated to America mid-1818;

and he returns some borrowed books. At the end of the month, Keats briefly entertains

becoming

a ship’s surgeon or moving to Teignmouth, though by the end of the month he remains

committed

to conquering

his current lack of inertia by writing some grand Poem

(letters,

31 May). We hear nothing about his love, Fanny

Brawne, though of course we don’t know everything.

What we do know Keats does around May, though, is compose poetry that centrally contributes

to the reason he becomes a canonical and hugely influential poet. In fact, by the

fall of

1818, which is the year of maturation before the maturation poetically shows, Keats

is himself

quite sure of his abilities: I think I shall be among the English Poets after my death

(letters,14 Oct 1818). He has some sense of what he might achieve: The faint conceptions I

have of poems to come brings the blood frequently into my forehead

(letters, 27 Oct

1818). Spring 1819 in fact makes this placement and those conceptions

so: in writing

odes on indolence, melancholy, a nightingale, and a Grecian urn (though the indolence

ode

might have been composed a little earlier), his position among

the great becomes set.

The other so-called great ode

is To Autumn, which is written later, in

September. It is, in fact, his last masterwork, and perhaps his best.

The exact compositional order of the spring odes is uncertain. They can, however,

be seen as

a loose series, or at least as interconnected lyric poems in which Keats uniquely

adapts and

massages the sonnet form within the greater style of the odal hymn. Perhaps significantly,

on

3 May, in the final part of letter to the George

Keats’s that begins 14 February, Keats expresses dissatisfaction with accepted sonnet

forms, and that he hopes to discover

a better form that avoids pouncing rhymes,

an overly elegiac tone, and ineffectual final couplets. Why this is singularly important

is

that the odes Keats will write in 1819 employ a unique and uniquely effective 10-line

stanza

to capture his own voice and intention, as well as to structure the fine-drawn and

subtle

dramas his poems enact (To

Autumn has an 11-line form). The form also promotes a fairly concise

integration of elements, and therefore renders topical and thematic unity. Finally,

the form’s

adapted traditional roots do not peg these poems as either trendy or dated. It would

have

taken Keats some serious study (and critical brilliance) to come up with these impressive

insights. Keats has worked to the realization shared by many great artists, that form

is, in

effect, everything, and that without an appropriate form, the subject troubles to

find

expression, and is thus potentially wayward. In Keats’s mature phase of composition,

form is

central to both his expression and understanding.

Keats’s striking originality in the odes is, primarily, that the speaker develops

such deep,

complex, and equal empathy for his subjects no matter how concrete (an object, a place,

a

particular moment) or abstract (an emotion, a feeling, an idea). This empathy, though

necessarily in flux and uncertainty, goes beyond just mustering descriptive or imaginative

capabilities. In Keats’s own terms, the subject needs to be set forth in such ways

as to allow

us to be intense upon

it without excess (that is, without sentimentality, and without

too much reaching after Delphic delicacies), and then also set forth and dramatized

in order

to make all disagreeables evaporate, from their being in close relationship with Beauty

& Truth

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817). As Keats suggests, the subject is all, and it

cannot be cloying or obtrusive in its representation (letters, 3 Feb 1818).

The odes, then, are varying dramas of controlled intensity without too much overreaching,

with speakers who range from seeming to be about to give into desire and uncertainty,

to

speakers who explore and represent subjects with perfectly toned restraint, tranquility,

and

even reason—and reason that, remarkably, is determined and tempered by sensuality

as much as

by thought. Keats’s great achievement takes place as these speakers seem wholly and

empathetically attuned to their subjects. In all of this, Keats’s poetics are quite

forcefully

enacted in the odes without (to use Keats’s terms) a palpable design

put upon the

reader (3 Feb 1818). His poems do not declare, Look what I can do!

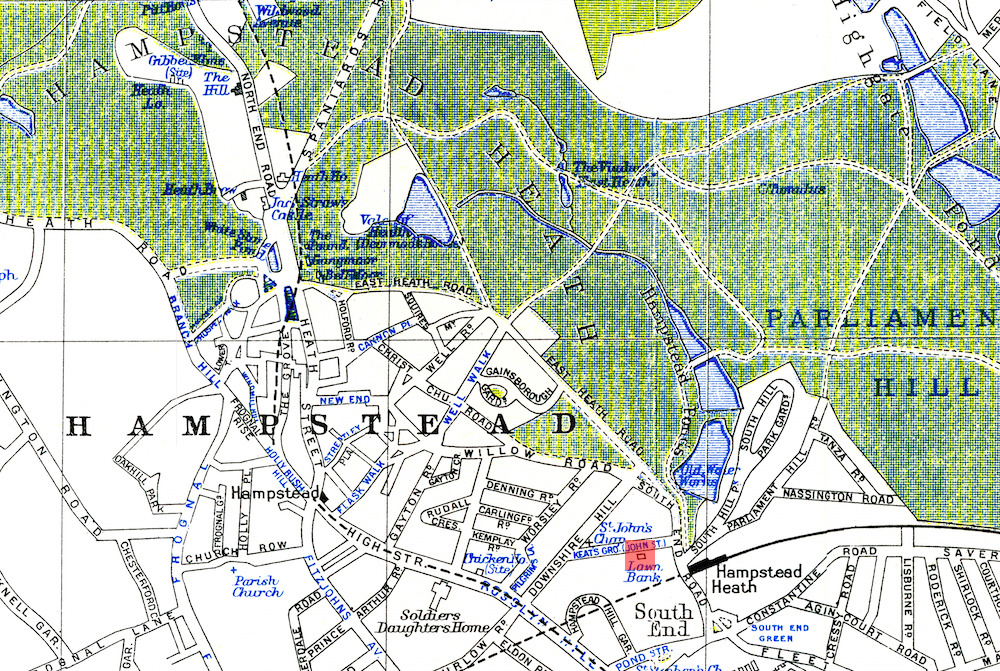

View of London from Hampstead Hill, James Paine (British Museum, 1880, 1113.5578)

While these odes offers us the symbolic as a way to develop a relationship with the poem’s subjects (what else can poetry really do?), we simultaneously remain grounded in the details of the material as we move between, for example, the real and the ideal, waking and sleeping, mortality and eternity, motion and stillness: the speaker can experience confusion, longing, ecstasy, sorrow, resignation—but these forms of mutable truths are to be embraced by their proximity to beauty, rather than as some position that expresses the poet’s egotism, subjectivity, or certainty.

The history these poems draws us into is not Keats’s own Regency era. Keats’s progress

takes

him to a point where the history that his poetry reflects is not just of a time or

place or

politics, and that is one of the reasons why his poetry continues to intrigue us—or,

to borrow

phrasing from the poems, they tease us out of thought

(Urn, 44), and they will not be

consumed by hungry generations

(Nightingale, 62). To put it another

way, the speaker within a history addresses that which is outside of history via the

viewless wings of Poesy

(Nightingale, 32)—this at once offers

both loss and consolation, along with profitable not-knowing. Urns, birds, states

of mind, and

a season: these stand before us now (consolation), and they will stand when we are

gone

(loss). So will Keats’s poems about them stand before us; they will remind us of and

reflect

our life, now and beyond—our experience or sensations turn or evolve into something

more

lasting; thus this spring Keats calls the life we live a vale of Soul-making

(letters,

21 April).

Again, we can historicize and politicize Keats’s poetry, but perhaps best so with

the

critical provision that Keats’s poetic progress reflects his conscious desire to be

able to

write poetry outside of his time and place, in poetry that is actually about being

outside

time and place. In its own terms, the Grecian urn is much more of a historian

of

eternity

than of a specific moment in classical or contemporary times; the

nightingale’s song reaches across generations. That is, we can of course place Keats

in

material history or attach him to an ideology or coterie, and that has been done,

as they say,

to death, and often with much resolve. But what can’t be placed in history? What isn’t

ideological? What artist is completely outside of a circle of other artists? The paradox

in

reading Keats is that his growing and purposeful resistance to writing poetry that

languishes

in politics makes it, at some level of logic, political poetry.

Keats’s poetry, then, does not constitute an act of evasion of the contemporary scene,

but a

willed encounter with these clamoring forces in order to move through and rise above

them;

thus his aesthetic desire and artistic goals confront history’s custodial qualities.

Think,

for example, of what, for Keats, the pale knight, the urn, the nightingale, and autumn

represent: not his time, not his place, not his politics; rather, they represent philosophical

and aesthetic ideals that uniquely address and represent the complexities of human

nature, the

capable and empathetic imagination, and the persistent power of and need for enduring

art.

When Keats very deliberately decides to study what he considers great poetry—whether,

Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, or Wordsworth, for example—it is genius, vision,

depth, and aesthetic longevity that attracts him; the persistence of form; the passion

for and

principle of beauty; but not a passing fancy to join the fashionable, though in the

first

phase of his writing this fancy was understandable irresistible. And Keats on more

than one

occasion makes it clear he looks down upon the trendy, what on one moment he calls

some new

folly to keep the Parlours in talk,

literary Bodies

that keep up the Bustle which I do not hear

(letters, ?29 Dec

1818).