24 February 1819: Indolence, Family Money, & Hopes for a Rousing Spring

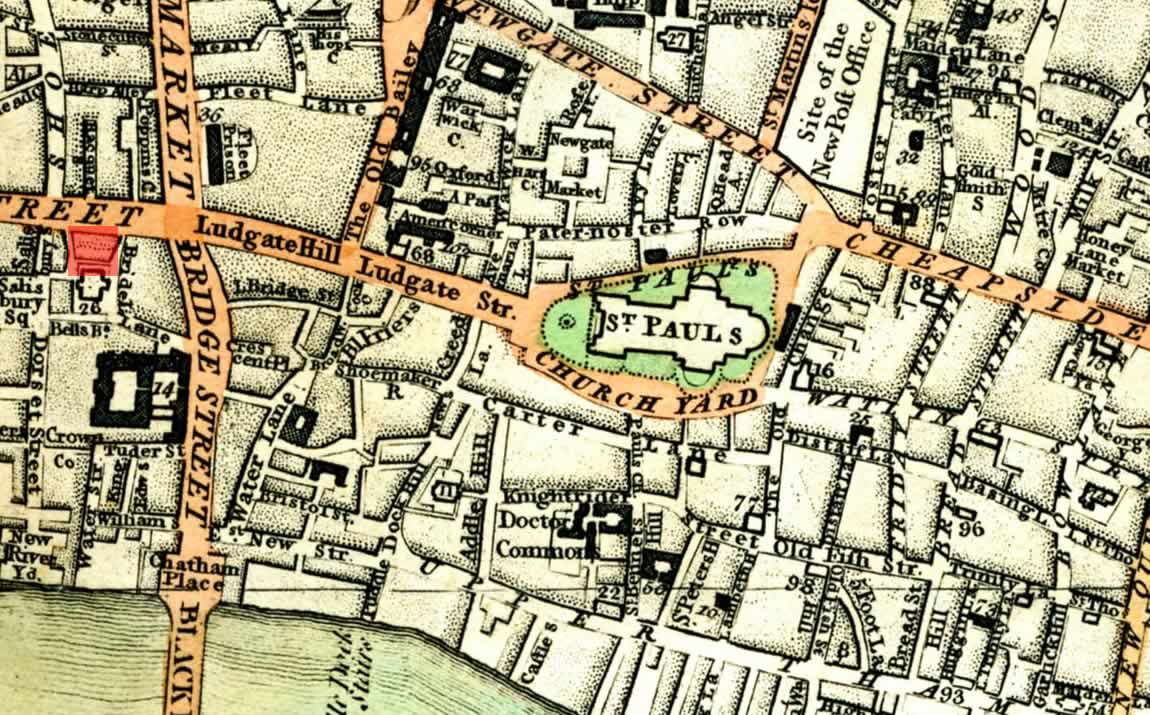

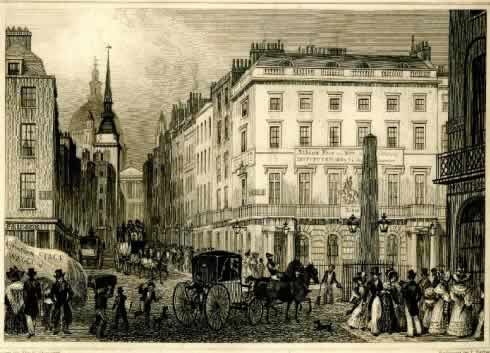

93 Fleet Street, London

Keats, aged twenty-three, comes into London from Hampstead for the first time in just about three weeks, staying at John Taylor’s on Fleet Street for a few days, 24-26 February. The scholarly and generous Taylor is a good friend to Keats, and he is half of the publishing company of Taylor & Hessey, which publishes Keats’s 1818 Endymion and will go on to publish the extraordinary 1820 collection; they also acquire rights to Keats’s first, volume, Poems (1817), from the Ollier brothers. Both Taylor and Hessey fully believe in Keats’s poetic gifts and personal qualities. Unlike his arrangement with the Olliers, Keats will not have to cover publication costs.

Keats has spent some time indoors because of a chronic throat. He rightly fears cold weather, and he has had medical advice to avoid it.

Keats sees family trustee, Richard Abbey, a

number of times in February, and he writes a least one firm letter to the obdurate

Abbey about

money issues; Keats needs more just to keep solvent. But Keats has to take some responsibility

for his situation, since, from 1816, he has been living almost exclusively on credit

based on

his inheritance money, and it appears that this credit may be used up by mid-year.

Keats feels

he is living as prudently as it is possible for me to do

(letters, 14 Feb), though,

given the amount of interest generated by the inheritance money, he has in fact been

living

beyond his means. In light of the death of his younger brother Tom at the end of 1818, Keats is uncertain if he can get his

share of the family estate until his younger sister, Fanny, is of age (letters, 20 Feb). Keats is also upset that Abbey has removed Fanny

from school.

Beyond Abbey, and despite his health issues, Keats manages to see and dine with some friends and acquaintances, go to a tavern (he loves Claret extraordinarily, it seems), and attend a birthday dance.

Perhaps as a diversion (or as a kick-start), Keats makes some fragmented beginnings on another poem, The Eve of St. Mark—a poem that, once begun, Keats feels indifferent about finishing. He dabbles with the poem for a few days in the middle of the month. But his creative and psychological energies are not strong enough to push it or him along, or perhaps the idea of another poem about some kind of legend simply came to bore him. What he leaves us with, in effect, is a fairly simple and only slightly evocative sketch, extraordinarily unlike the more allusive and atmospheric The Eve of St. Agnes.

Generally, and despite the obvious accomplishment made by The Eve of St. Agnes, the very early

part of 1819 finds Keats somewhat listless and accomplishing little—indolence

might be

the word to best describe his brooding and brewing state, and word Keats himself uses

and

often thinks deeply about. On 14 February Keats writes, I have not gone on with

Hyperion—for to tell the truth I have not been in great cue for writing lately—I must

wait

for the spring to rouse me up a little.

It indeed turns out to be quite a spring

rousing, given the quality of poetry to come. This relatively dormant period of a

few months

in early 1819 is, in fact, central to his progress, even if, by mid-April, it worries

him. We

in fact see this brooding and brewing in that 14 February letter, which turns becomes

a long

journal letter that ends 3 May (to his brother and sister-in-law in America): it contains

passages that provide a partial record of Keats’s leap to poetical maturity as he

works

through ideas and subjects that end up in his best poetry (for more about the importance

of

this letter, see progress factor #10 here).

To borrow from Keats’s own wording about his own poetic progress, he knows what he needs to do, how to do it, but he now just has to do it (letters, 10 Jan 1819). And in moving forward, thoughts about subject, tone, and form profitably fuse in and through this period of contemplation in the early months of 1819—becoming, in the end, uncommon poetic practice. No apologies, no limiting occasions, no cloying desire to be a poet, and no treacly prettification will inhabit this new round of composition.