18 January 1819: Chichester, Bedhampton, Haydon as Martyr, & The Eve of St. Agnes

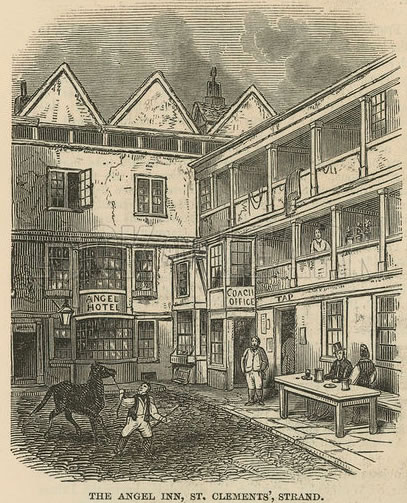

Angel Inn, the Strand, London

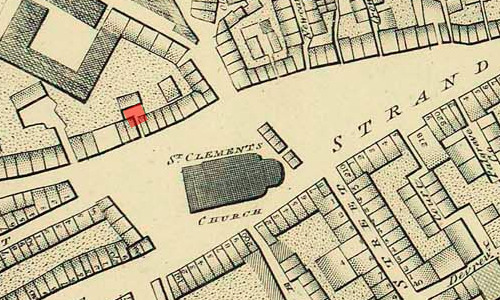

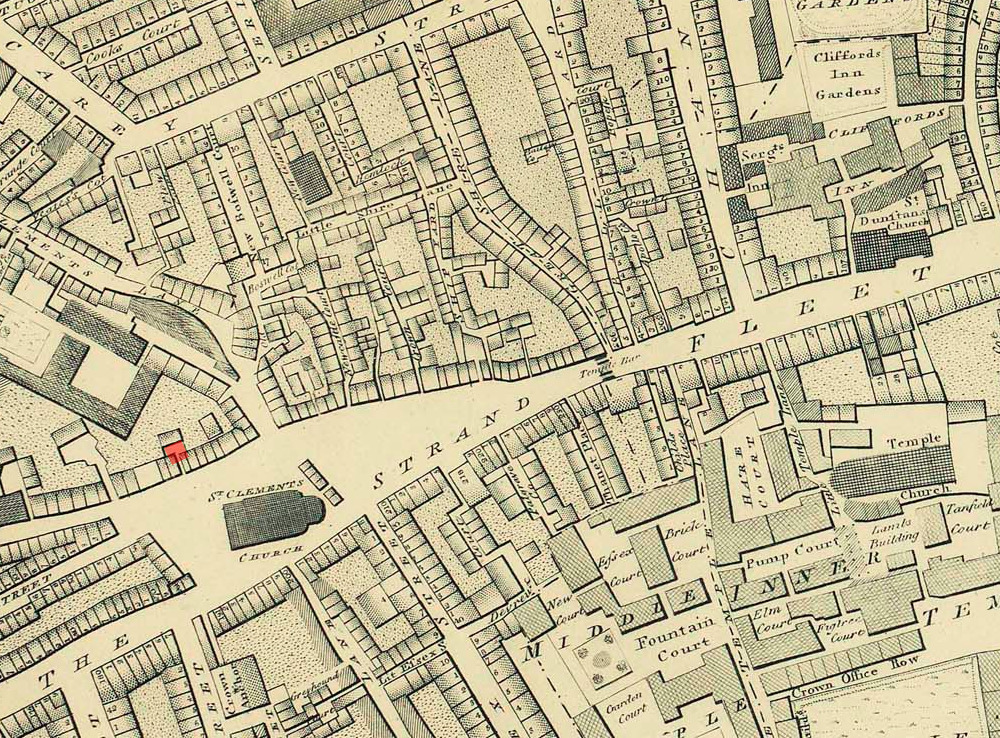

After Keats squeezes 20 pounds from Richard Abbey—who, as family trustee, at times tight-fistedly and opaquely manages the Keats family estate—on 18 January, Keats catches a coach to the old town of Chichester (a 60-mile, 12-hour trip), leaving from the Angel Inn off The Strand. At Chichester, Keats stays near Eastgate Square (where, since 2017, there has been a sculpture of Keats by Vincent Gray.)* Meeting up with his close friend and roommate, Charles Brown, Keats spends a few days with the welcoming parents of one of his friends, Charles Wentworth Dilke.

Given the relatively recent death of his younger brother, Tom, and the crucial business of refocusing his own situation and goals—not to mention his stress about lack of contact with his younger sister because of Abbey’s frustrating restrictions—the vacation is probably a good thing.

In Chichester, Brown, with some lighthearted

turns (including shaving his mustache upon request and an early-morning old-lady

impersonation), makes the stay pleasantly distracting. It is hardly imaginable, but

Keats also

actually goes to a few old dowager card parties

—so he writes.

On 23 January, Keats and Brown move on to Bedhampton (about 12 miles away) to stay for just over a week with Dilke’s sister’s family.

During this approximately two-week period, Keats thinks about and drafts a poem about St. Agnes’ Eve (which is on 20 January), based on a folk tradition with Roman origins: young virgins dream of their future husbands. In his romance of deep, evocative contrasts, Keats, somewhat controversially, brings the warm dream into cold reality in a scene that still haunts and divides critical opinion; the apparent future husband actually sneaks into the young woman’s bedroom and, as it were, enters, her dream. But is this rape? Deception? Love? The precariousness of romantic expectation? An allegory of a dreamer’s confrontation with reality? A creative exploration of the power of a too-capable, idealizing imagination? The general subject seems to have been suggested by an older woman of independent means with whom Keats has been earlier romantically involved—the mysterious Mrs. Isabella Jones—though now she remains a lingering acquaintance. [For a deeper reading of the poem, go to 2 February 1819.]

The Eve of St. Agnes is published in Keats’s final 1820 volume, along with other poems, most of which he will soon write—poems that, in fact, are the overriding reason we bother much with Keats. Against his will, Hyperion is also published in the 1820 volume; it will become greatly praised, despite remaining a fragment.

All of this—moving on from Tom; being fully committed to literary study and to his poetry; tasting some accomplishment by applying a fully developed poetics (of synthesized disinterest and intensity) in both Hyperion and The Eve of St. Agnes; his feeling that he knows what he needs to do and how to do it (letter 10 Jan); profitable moulting; as well as resolving not to publish a new volume until he is satisfied with the quality of the work—all of this sounds a soon-to-begin remarkable period of poetic production . . . in fact one of the most remarkable in English literary history.

Keats’s friend—the ever-encouraging and perhaps over-attached supporter, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon—asks Keats for a loan (in early January), to which Keats agrees—without interest, Keats insists. Keats, we know, is himself always strapped for cash with his finances extremely uncertain—he has been living on credit (and beyond his means) for a while, and this will soon run out without him ever being aware of other available funds sitting in Chancery (perhaps as much as 800 pounds). Haydon has notorious problems with his own personal finances and hovering creditors; he will ask for another loan in March. Haydon also has the further problem of overestimating his artistic worth and opinions—and does so quite publicly. He tends to see himself as a victim or martyr, and an extremely quarrelsome one at that. But, for most of the time Haydon and Keats associate with each other, there is clear intimacy and support. Together they enjoyed gossip, mutual flattery, and, it seems, reading Shakespeare together.

There is little doubt that an important component of Keats’s poetic development evolves from seeing and assessing painting and sculpture, and Haydon’s determined views about the importance of art no doubt prop Keats’s aspirations and direction. It is, after all, Haydon who exposes Keats to the Elgin Marbles back in early March 1817, and Keats at that point is clearly in awe—stunned, even—of their silent, penetrating, enduring beauty. The problem still lingers with Keats and figures importantly in his progress: How, then, to reproduce this effect in his poetry?

Ten years after Keats’s death, Haydon in his remarkable journal (for 14 November 1831)

records dreaming of Keats, in which Keats reminds Haydon to make a drawing of my head

before I die.