10 January 1819: Haydon, Moulting, Stalled Hyperion, & a Sequestered Sister

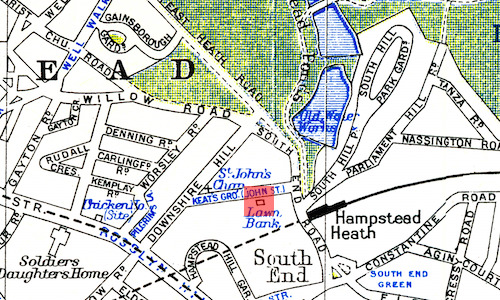

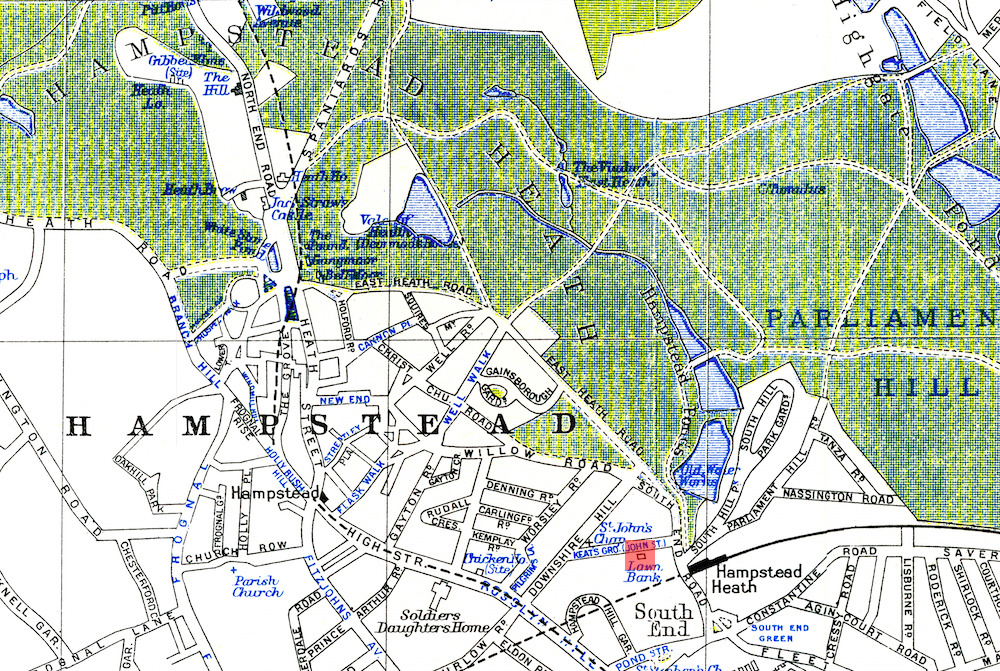

Wentworth Place, Hampstead: a double-house where Keats, aged 23, has lived with Charles Brown since early December 1818, almost immediately after the death of his younger brother, Tom, of consumption.

What also concerns Keats at this time is the restricted contact he has with his younger

sister, Fanny, orchestrated by the family

guardian, Richard Abbey. Abbey even objects to

Keats writing to his sister, which bothers Keats considerably (letters, 16 Jan and

11 Feb

1819). To his brother George and wife Georgiana in America, he writes that Abbey has

quite shut [Fanny] out from me

(14 Feb).

In an exchange of letters with his friend and great supporter, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, Keats confirms that he will give Haydon

an interest-free loan, though Keats is himself strapped for cash, and living off dwindling

credit based on inheritance money. Haydon becomes overly and annoyingly persistent

in asking

Keats for financial assistance. Haydon (nine years Keats’s senior) has fallen on hard

times,

with some vision problems as he attempts to complete a large, complex, historical

painting.

Keats tells Haydon he is a little unhappy about procuring the Money,

since it involves

the ordeal

of going to town more than a couple of times and standing at the Bank

[for] an hour or two

—it is, Keats suggests, a torment worse than Dante’s circles of hell

(10 Jan). He has a point.

Haydon, throughout much of his relationship with Keats, passionately encourages Keats’s poetic development by offering brotherly affection. Haydon, too, importantly pushes Keats to avoid Leigh Hunt’s sway (Hunt unofficially mentors and promotes the young Keats beginning late fall, 1816). By 1819, Haydon is less important for Keats, but Keats remains mainly loyal to him. One of Keats’s most mature characteristics is to accept friends while being aware of their faults; Haydon had many.

Haydon paints Keats into his epic (in terms of the time taken to complete it, too!) canvas, Christ’s Triumphant Entry into Jerusalem. In mid-December 1816, Haydon also makes a life-mask of Keats, which must have been a moment of stirring pride for Keats, since, the year before, Haydon had also made a life-mask of William Wordsworth, arguably the most important poet of the age.

Importantly, in this letter of 10 January (which Keats signs off, Your’s for ever

),

Keats perceives some slow but sure way forward in his progress as a poet: I see by little

and little more of what is to be done, and how it is to be done should I ever be able

to do

it.

With some feeling he adds: On my Soul there should be some reward for that

continual ’agonie ennuiyeuse’ [tedious agony].

This is a fairly deliberate but tempered

statement of both struggle and poetic progress: Keats has come to see

the character of

great and enduring poetry, and his remarkable poetics point to how

he should do it.

In fact, Keats’s way forward will come more quickly than he thinks. With his efforts on the Hyperion poem stalled, he soon finds himself propelled by an evocative, atmospheric, and controlled romance, The Eve of St Agnes, drafted the last two weeks of January, and with the coming spring Keats’s progress is little short of astonishing.

Keats also writes to Haydon that lately he has

written little; he has been disconnected and as it were moulting.

Keats then adds that

his state will not take him to the rope or the Pistol

—that is, to suicide. Four days

later, attempting to cheer Keats up, Haydon tells Keats that what he feels is nothing

more

than the intense searching of a glorious spirit,

and that bye & bye

Keats

will shine through

the muddy world

(14 Jan). These are kind, encouraging words.

Knowing what we know, what Keats says about not contemplating suicide carries a minor

but dark

irony: Haydon, unfortunately, does commit suicide (in fact, a grizzly

suicide) years later, in June 1846. In the end, Haydon fails to achieve his larger

artistic goals and to convince the world of his own artistic worth (which he sadly

overestimates); he also had a way of affronting both patrons and the artistic establishment,

and of chronically gathering numerous creditors.

The moulting

metaphor is useful, given that Keats also uses it later in the year in a

letter to another close friend, John Hamilton

Reynolds, 11 July: I have of late been moulting.

But in this case, Keats

describes his change not into a bird or butterfly (he’s been there and done that),

but

something of the reverse: in fact, he is more grounded (sublunary

), more like a

Chrysalis

with little peepholes able to look out into the stage of the world.

This is a statement of maturity and poetic perspective; and given what he writes in

the first

half of 1819, this is indeed an accurate self-assessment of his progress—or the style

of his

progress. The Chrysalis with peepholes idea—that is, of seeing-and-not-being-seen—fits

with

his notion of the poetic character as unobtrusive and camelion-like.