31 December 1817: The Dimensions of Poetic Accomplishment for Keats; or, The Anti-Wordsworthian Wordsworthian

Hampstead Heath

On the last day of 1817, Keats, while out walking on Hampstead Heath, runs into William Wordsworth. Wordsworth may have been returning from seeing his old friend and collaborator, the great poet and critic, Samuel Taylor Coleridge (who is staying in Highgate). Keats is in his early twenties; Wordsworth is approaching fifty.

Keats had met Wordsworth, already a living

legend, earlier in December through their mutual friend, the historical painter, Benjamin Robert Haydon. Looking back almost three

decades, Haydon recalls that at this juncture Keats is a Young worshipper

of

Wordsworth. By 31 December, Keats has met Wordsworth at least twice, including the

so-called

immortal dinner

at Haydon’s on 28 December (see 28 December

1817 for more about the event); and over into January 1818, Keats sees Wordsworth a few more times.

Back in November 1816, just a few weeks after Keats meets Haydon, Haydon tells Keats

he will

send Keats’s sonnet Great Spirits now on earth to Wordsworth, a poem that praises Wordsworth as

one of those Great Spirits.

For his part, Wordsworth, in somewhat constrained terms,

reports back to Haydon on 20 January 1817 that the poem is of good promise [ . . . ]

vigorously conceived and well expressed [ . . . ] and the sonnet is agreeably concluded.

Worth noting is what in part the poem so agreeably well expresses: praise of Wordsworth.

For

his part, Haydon believes he shares the mantle of genius with both Keats and Wordsworth,

and,

like them, is graced with a higher calling.

Wordsworth is the most important contemporary influence on Keats’s best poetry—that is, his poetry to come. Yet it appears that Keats does not really begin to seriously study Wordsworth’s poetic style and accomplishment rigorously until the last months of 1817. Until then, other figures like Milton, Shakespeare, Spenser, Chatterton, Homer, Virgil, and Byron take up much of Keats’s developing critical attentions. Keats thus becomes keen to deliberately parse Wordsworth’s greatness and poetical character; more interestingly, Keats will articulate what he wants to emulate and what he wants to avoid. This becomes a singularly important reckoning.

Although age, education, politics, life-style, and cultural distinction separate Keats

and

Wordsworth (yet somewhat parallel family

histories actually join them—both poets lose parents at an early age), Keats is nevertheless

drawn to Wordsworth. The attraction carries more than a fan/celebrity dimension, though

no

doubt it plays a part. How could it not be exciting for young Keats to meet the great

man from

the Lakes? When Keats is told by Haydon that he will be showing some of Keats’s work

to

Wordsworth, Keats says the idea put me out of breath

(21 Nov 1816).

Beyond Keats’s initial giddiness, we cannot over-estimate how meeting Wordsworth would

have

inspired Keats. But, as suggested, there are complexities. When we examine and tally

Keats’s

relationship to and regard for Wordsworth, at least four versions of Wordsworth emerge:

the

poet whose poetic and philosophical depths are almost peerless and to be emulated;

the poet

whose style—what Keats famously calls the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime

(27 Oct

1818)—is key for Keats in formulating his own very different poetical character and

direction;

the poet whose conservative turning and political affiliations lends Keats to declare,

Sad—sad—sad

(26 June 1818); and, as a conflated figure, the poet whose own personal

egotism, vanity, and bigotry (letters, 21 Feb 1818) leaves him in what Keats calls

a

Shell,

protected by his devoted sister and his wife (letters, 21 March 1818). But it

is the first two of these that are, in terms of Keats’s progress, by far the most

important.

Keats is obviously willing to overlook the politics and the person in order to pay

homage to

the genuine achievement of a philosophical poet.

Both direct and allusional evidence point to Keats being familiar with most of Wordsworth’s significant early poetry, which

includes Lyrical Ballads, the 1807 Poems in Two Volumes, and the slightly later The

Excursion, 1814, which Keats knew very well. If Keats did not own all of Wordsworth’s

published poetry, a number of his close friends owned a great deal, and book-borrowing

was, in

a way, a life-style for Keats. Keats also certainly read some of Wordsworth’s poetry

in

magazines, including The Examiner and The Friend. And at least three of Keats’s friends wrote about

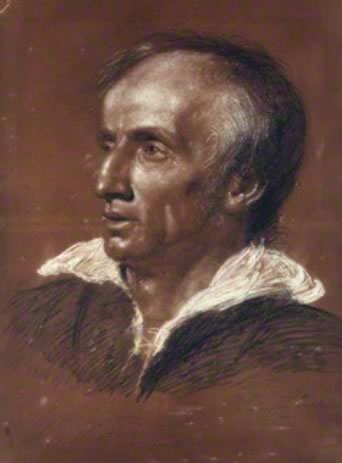

Wordsworth (Leigh Hunt, John Hamilton Reynolds, and William Hazlitt). Further, Keats’s friend Haydon had painted and made a life-mask of Wordsworth, and Haydon

would include Keats and Wordsworth in the same part of his of huge heroic-historical

painting,

Christ’s [Triumphant] Entry into Jerusalem.

In an otherwise very crowded painting,

Keats is placed just beyond and behind Wordsworth, which perhaps suggests Haydon’s

reading of

the relative situation of and connection between the two poets.

That Keats’s friends hold strong, varying, and evolving opinions of Wordsworth’s poetry leaves Keats to independently work through

his sense of Wordsworth’s influence and accomplishment. Again, this independence is

central to

Keats’s progress (letters, 8 Oct 1818). Keats thus sets himself the task of evaluating

the

nature of Wordsworth’s genius,

part of which he does in a remarkable letter to Reynolds, 3 May 1818: he attempts to figure out

whether or not Wordsworth has an extended vision or a circumscribed grandeur.

Part of

Keats’s conclusion to the crucial and complex question is that Wordsworth, perhaps

more than

any other poet, can deeply think into the human heart

in all the burdened mystery it

must bear, which suggests that Wordsworth possesses both an extended vision

and a

circumscribed grandeur

—moreover, they are, in fact, possibly the same thing, given that

they are channeled or focussed by Wordsworth’s voice that is, paradoxically, at once

magisterial and subjective; Wordsworth’s power is to transform the personal into the

universal

(though some would suggest that his poetry too much privileges the former). This poetic

complexity is conveyed best when, in Tintern Abbey, Wordsworth

speaks of seeing into the life of things

(49), and when he notes that the mind of

man

is part of all things

(93-102). That is, seeing into the life of things is an

act both expansive and confined. Wordsworth’s territory: The still, sad music of

humanity

(Tintern Abbey, 92).

The ability to think into the human heart is what Keats will also want to poetically

achieve,

though his strategy or style (that so-called poetical character) ends up being driven

largely

by imaginative empathy rather than subjective egotism. Hazlitt, in an essay that Keats reads, puts it simply and profoundly: he writes that

Wordsworth

sees himself in all things

(The Round Table, 1817).

Wordsworth absorbs the subject; Keats is absorbed by the subject. Wordsworth feels,

and then

thinks, his way into his knowledge of a subject; Keats uses imaginative capabilities

as a way

of knowing, since it allows uncertainty as an equable state.

In the end, though, Wordsworth in his most memorable (and generally earlier) work articulates forms of restoration, healing, reconciliation, and immortality in the face of loss, suffering, mutability, and mortality. Keats never quite achieves such a sustained vision, but he comes to recognize that Wordsworth’s accomplishment necessarily urges aspects of his own progress. Keats is profoundly an anti-Wordsworthian Wordsworthian.