26 December 1817: Harlequin’s Vision & Philosophical Directions: Kean, Shakespeare, & Wordsworth

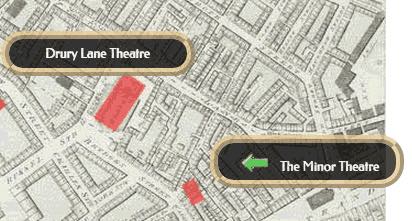

Drury Lane Theatre, London

Keats has seen Edmund Kean, perhaps the premier (and certainly the most controversial) actor of the era, perform the title role Shakespeare’s Richard III on opening night, 15 December, at Drury Lane Theatre.

Keats reports in a letter that Kean acted finely

(letters, 21 Dec 1817), and he

discusses Kean with other friends over the next few days. On 21 December, his review

of Kean

appears in The Champion, where he stands in as reviewer for

his friend, John Hamilton Reynolds, who is out

of town in Devon. For the review, Keats also draws upon other performances of Kean

he has

seen. Keats sees at least part of the play again on 12 January 1818.

On 26 December, Keats sees the play (pantomime) Harlequin’s Vision with his very good friends Charles Armitage Brown and Charles Wentworth Dilke, also at Drury Lane Theatre. Keats’s review of the play (and of Retribution, as well—likely seen 1 Jan 1818, at Covent Garden) appears in The Champion, 4 January 1818.

Keats late this month begins to formulate a poetics in his letters that, in about

a year,

lead to some definite, and perhaps stunning, changes and leaps in the quality and

character of

his poetry. One of Keats’s pivotal conclusions (apparently arising first in discussion

with

Dilke) connects with his emerging ideas about superior literary achievement: that

the

excellence of every Art is its intensity, capable of making all disagreeables evaporate,

and that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or

rather obliterates all consideration.

Keats feels this is exemplified by Shakespeare,

and is exampled in Shakespeare’s King Lear (letters, 21/27 Dec). Although thinking and feeling are

conflicting or even contrary states of human behavior and experience, it is nevertheless

possible to represent these poetically—as both beautiful and therefore true. To be

embraced

are those disagreeables,

all those uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts

—the

quality

forms a Man of Achievement especially in Literature.

Keats secures

this aspirational quality Keats secures in a single, memorable term, Negative

Capability. [For a more full treatment of Keats’s letter that describes his

arrival at Negative Capability, go to 27 December 1817.]

Here, then, as mentioned, Keats by name celebrates the nature of Shakespeare’s achievement—he, writes Keats, is the one who

possesses these qualities so enormously.

But Keats also momentarily brushes up against

William Wordsworth’s territory—poetry as

philosophy, philosophical poetry. We glimpse this when, in analyzing Kean’s intense

and

ranging acting style, Keats, notes that Wordsworth, too, feels his being

deeply. But

the poetic problem for Keats will be how not to channel such depth through a dominating,

lyrical subjectivity—what Keats ten months later will more exactly term the wordsworthian

or egotistical sublime

(letters, 27 Oct 1818). Keats thus desires poetry as deep and

searching of nature and the human condition as Wordsworth, and his underlying model

almost

certainly springs from Wordsworth’s seminal poem, Tintern

Abbey. But how can he, following Wordsworth, likewise see into the life of

things

(Tintern Abbey, line 50)? How can he fathom and

poetically represent what Wordsworth calls the burthen of the mystery

(line 39) without

employing a legislating poetic subjectivity, one that displays both personal and locational

history? Keats will only be able to poetically manifest answers to these questions

in his

poetry of 1819, and most strikingly in To Autumn, which is his version of the

Wordsworthian seeing-into-the-life-of-things. Keats’s great poem (perhaps greatest

poem) looks

out in the landscape and does indeed see into it, into its eternal, beautiful qualities

that

connects the stilled movement of all things, holding, at once, and with embraced tranquillity

and subtle sensuality, intimations of life and death. And he does so without that

legislating

Wordsworthian I.