14 December 1817: Keats & the London Liberal Intelligentsia

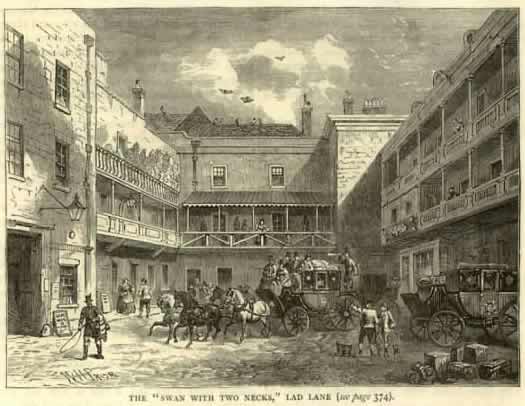

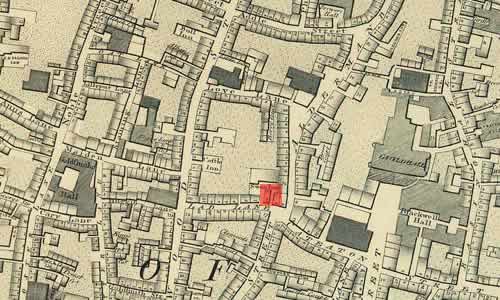

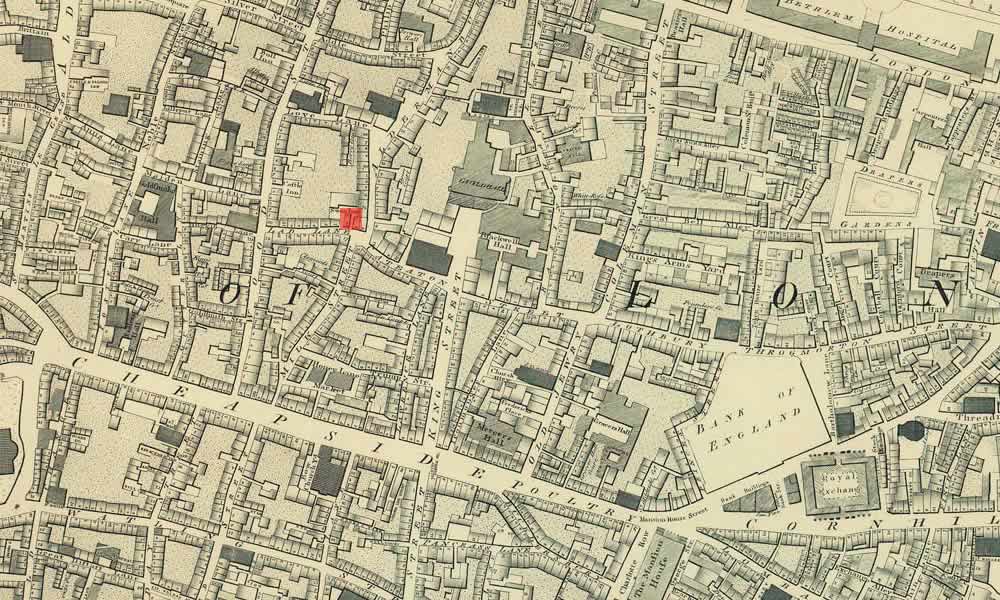

Swan With Two Necks, Lad Lane, London

Where Keats sees off his two younger brothers Tom and George, who are traveling to Teignmouth, Devon. Tom is increasingly ill with consumption. Later in the day, Keats dines with his affectionate friend, the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, who will very shortly arrange an important meeting for Keats with the leading poet of the age, William Wordsworth.

Despite having worked hard to complete a first draft of his long poem Endymion (which he does at the end of November), for Keats the last three months of 1817 are extremely social, as they generally have been since being introduced into a part of London’s liberal intelligentsia via Leigh Hunt in October 1816. During these three months, and mainly around town, he goes to the theatre, attends dinner parties; he socializes with many of his friends, and with most of them on more than one occasion (there were others, too, not as close): besides Haydon, Keats sees Benjamin Robert Bailey, John Hamilton Reynolds (and his family),Leigh Hunt, Percy and Mary Shelley, Charles Brown, James Rice, Horace Smith, John Taylor, James Hessey,Charles Wells, Thomas Hill, and Charles Wentworth Dilke. Keats also meets William Wordsworth, William Hazlitt, and Charles Lamb, and he has met William Godwin. Other friends, like Joseph Severn, also trail into this group. So, too, does the trustee of the family money, Richard Abbey, have his tea-brokering offices and London, and Keats spends much too much time trying to acquire bits and pieces of his entitlement (Keats seems to have no idea about the significance of his share, and the money he receives is based on credit based from his own share of the dwindling family legacy). [See here for a graphing of Keats’s social and intellectual network.]

In terms of Keats’s poetic development, frequent and fairly intense contact with such friends and acquaintances—where discussions about poets, poetry, art, drama, theatre, and publishing are no doubt common—profitably propels Keats to formulate his own opinions while gathering and assessing the ideas of others. Keats also reads some criticism during this period, and in particular Hazlitt’s 1817 Round Table collection of essays (along with pieces by Hunt). Hazlitt increasingly becomes a significant influence on Keats’s tastes and thinking. Further, during these last three or so months of 1817, as Keats assesses the critical significance and poetic worth of his Endymion (he finds it sorely lacking but necessary to move forward), his poetics develop significantly, thus signaling crucial directions for his poetry-to-come. He will turn to subjects less random or overly occasional—ones that don’t conspicuously cue Keats’s favorite early bounded subject: I want to be a poet. But at this point he remains a poet very much in search of voice, subject, and form. Along with this (or as a part of this), and relative to all those opinions that must have marked his social life, Keats is also in the process of articulating an independent voice based on his breakthrough idea (developed and articulated toward the end of November) that nothing can be truly known by reasoning alone. What roles does sensation play? The imagination? Perception of beauty? These are powerful uncertainties.

What all this social contact amounts to is the obvious, that Keats is, so to speak,

thoroughly a London lad-about-town, and any ideas of the hermetic, purely solitary

Romantic

poet who spends all of his time fondling moss and gazing at the far landscape should

be

dispelled. Keats’s social life only begins to wind down toward the end of 1819 and

into 1820

as consumption, the wasting

disease we know as tuberculosis, begins to confine and

depress him. Keats does, though, like anyone else, at moments crave solitude—he needs

to

think, study, and write. And, perhaps more importantly, he comes to associate the

Pleasure

in Solitude

with not just ambitions of my intellect

but with what essentially

drives him and his work forward: the yearning Passion I have for the beautiful

(letters, 24 Oct 1818).

As suggested, Keats’s most important directions are beginning to be set in his theories

(manifesto-like, in a way) about imagination, artistic intensity, the character of

poetic

greatness, the qualities of genius, truth and beauty, and Negative Capability

(see 22 Nov and 21/27 Dec 1817 for articulation of these theories). What is interesting,

though, is that Keats’s poetics—which, in his case, reduces to what to do and how

to do

it—evolve in advance of his poetic practice and development. In short, we have to

wait about a

year before Keats’s poetry begins to capture perfectly measured intensity, formal

control, and

a capable imagination.