March 1817: Hunt & Haydon as Keats’s Mentors; Toward Endymion

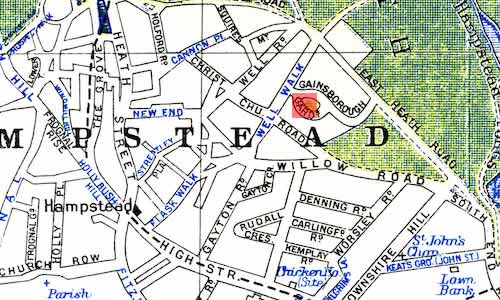

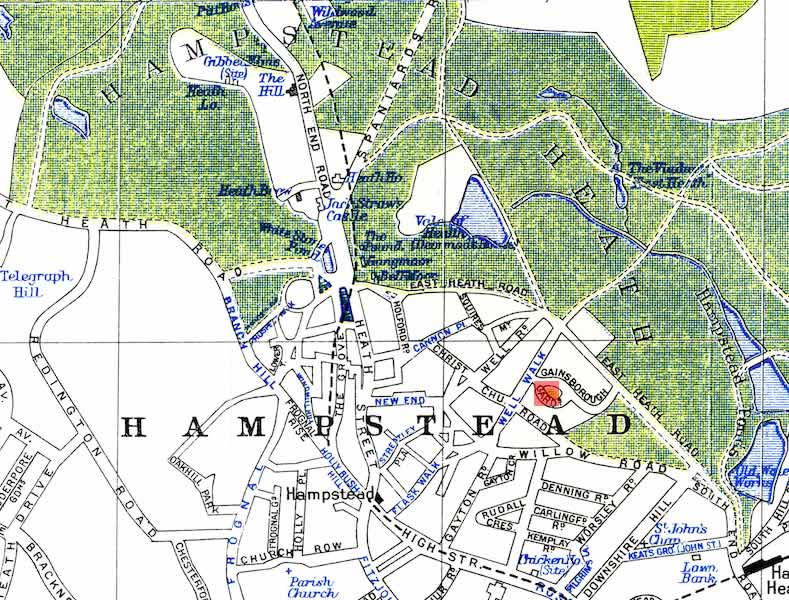

1 Well Walk, Hampstead

Where, toward the end of March, Keats (aged twenty-one) rents rooms with his younger brothers, George and Tom.

Being in Hampstead puts Keats a suburban milieu and coterie close to Leigh Hunt, who, beginning October 1816, encourages and unofficially mentors Keats, which is not surprising given Hunt’s reputation as a poet, critic, and celebrity journalist—and co-editor of the liberal paper, The Examiner.

[*See here for a graph of Keats’s network based on part of this coterie, with Hunt as a significant if not crucial hub.]

In the last four months, Hunt has published five

of Keats’s poems in The Examiner, and so connection with

Hunt has some advantages for young and ambitious Keats. Association with Hunt will,

however,

peg Keats as a certain kind of writer and thinker, and completely at odds with Tory

critics

and tastes. Later in this year, in October, Hunt will be nastily nominated as the

pretentious

Doctor and Professor

of the Cockney School

of poetry (in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine), and by August 1818, Keats will

be disparagingly joined to Hunt as his naive and ineffectual follower. By then, Keats’s

writing and poetics are purposefully moving beyond the scope of Hunt’s poetic influence—not

to

mention beyond Hunt’s poetic capabilities. But, for now, Keats will first have to

break away

from some of Hunt’s poetic traits, like feminine rhymes and adjectival daintiness.

He will

also have to evolve subjects less occasional and a voice less motivated by sociability;

this

begins to take place as Keats very deliberately studies great poetry, great art, and

important

literary criticism.

Since October 1816, and mainly through Hunt, Keats has quickly become friends with a network of artists, writers, critics, publishers, and other poets, all of whom begin to both prompt and challenge Keats’s ideas and aspirations. One of those new acquaintances Keats meets almost immediately via Hunt is the historical artist Benjamin Robert Haydon, and in early March, Keats sees the Elgin Marbles with Haydon. What Keats encounters profitably sticks with him, and the experience immediately triggers thoughts about weighted mortality in the face of immortal art and beauty, which is a subject to which some of Keats’s greatest poetry will, within a few years, return; but we see the topic signaled in two of Keats’s (thus far) better poetic efforts, both of which are published on 9 March: On Seeing the Elgin Marbles, and To Haydon with a Sonnet Written on Seeing the Elgin Marbles. Keats will also become intrigued by how art, though silent, possesses lasting power through its beauty alone.

Keats’s connection with Haydon is, at this point, intimate and mutually enthusiastic: as

Haydon writes to Keats this month, he vividly believes that Keats sympathetically

recognizes

his own talents and that burning ripeness of soul

: you add fire, when I am

exhausted, & excite fury afresh—I offer my heart & intellect & experience.

Haydon made a life-mask of Keats in December 1816, and he will also include Keats

in one of

his large historical canvases.

In March, Keats also writes a poem on Hunt’s poem,

The Story of Rimini. Keats’s sonnet—On The Story of Rimini—praises

Hunt’s sweet tale

with its bower-invoking delights.

As mentioned, Hunt and his

poetry openly influence Keats’s earlier work—Hunt at this point still hovers as a

kind of hero

and model for Keats—but, at least on one level, this is not necessarily a good thing:

in terms

of poetic style, Keats will have to move well beyond Hunt’s affected poeticisms and

use of

wispy description for description’s sake, entertaining though for some it might be.

Neither

professionally nor dispositionally is Keats like Hunt, though he is naturally impressed

by

Hunt’s amiability, reputation, energies, and connections, as well as his dedication

to

reformist political causes and to poetry. Hunt, for his part, will, even after Keats’s

death,

peg him as the beautiful young poet, and Hunt in fact seems to particularly like Keats’s

poetry when it sounds a little like his own, as when he praises a line in one of Keats’s

poems

as possessing delicate modulation, and super-refined epicurean nicety!

(from Hunt’s

essay on Keats in The English Poets, in vol. 4 of Hunt’s

complete works [1856], p.248).

During March, Keats sees his Poems collection published, the official ending of his position of surgeon at Guy’s hospital, poetry published in The Examiner, a strong review of Poems by his friend John Hamilton Reynolds in The Champion, and positive notice of his Poems in The New Monthly Magazine. Keats has to pay for the cost of publishing his collection to the Ollier brothers, Charles and James, who hope to make some capital from the project in the form of commission to help support their new company: the title page of Poems cites the printer as C. & J. OLLIER, 3, WELBECK STREET, / CAVENDISH SQUARE. There is also a quotation from Spenser on the page (Keats’s first poetical model) and an image of Shakespeare, though sometimes mistaken as Spenser. Probably upon the publication Poems, Keats and Hunt crown themselves with bardic laurel wreathes and celebrate the occasion by writing poems.

Besides being thrilled about all of this, no doubt Keats at this moment starts to

become more

conscious of his own poetic directions and tastes, especially given his awareness

that Poems is a bare step above juvenilia—a few years later, when he is

sick and all his writing behind him, Keats will refer back to this early poetry as

his

first-blights

(letters, 16 Aug 1820). Conversations with the likes of Hunt and Haydon, as well as with Reynolds and

the volatile young poet Percy Shelley and his

wife, Mary (in December and over into February),

can only have led Keats to reflect on the poet he hopes to become and the poetry he

hopes to

write. Plaguing Keats’s poetic progress are notions of fame and the poetry of occasion

and

sociability, often encouraged by Hunt. Keats might also have had thoughts about the

poetic

inclinations of Shelley, Hunt’s other apparent disciple. But Shelley’s reformist and

radical

politics, which are never far from the surface, does not strike a chord with Keats’s

more

filtered and pure literary aspirations. Keats will strive less for immediate relevance

than

for lasting capabilities. To elaborate and repeat: association with Hunt bogs down

Keats’s

reception in (or reduces it to) partisan politics, and though Keats’s natural ideological

sympathies largely correspond with those of Hunt, Keats’s values, beliefs, and judgments

increasingly focus on how to represent art’s truth and beauty in the context of imaginative

capabilities and human mortality. While of course everything can be reduced to (or

critically

forced into) the political, such reduction is in fact what Keats hopes to transcend

in his

poetry, and what motivates the kind of greatness Keats desires to achieve.

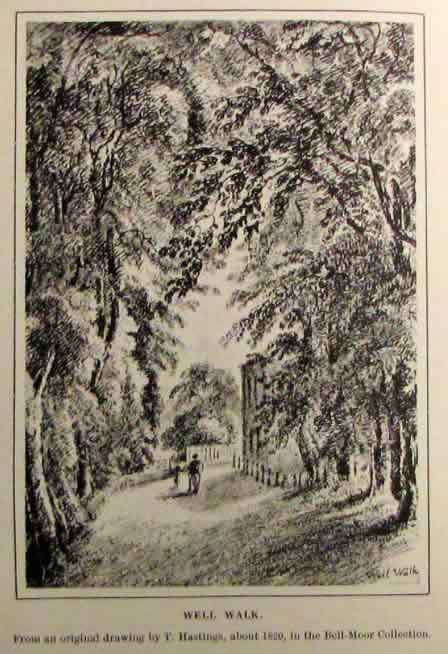

Near the Well Walk Hampstead,1828, by Thomas Hasting (British Museum)

Resolve to write a long and testing poem grows. Haydon advises Keats that he needs to be alone in order to improve

himself

(letters, 17 March), which marks a move away from Hunt’s sway. Keats heads out on his writing trip (to the Isle of Wight) to work on a

poem that, as a kind of self-imposed apprenticeship, will test his poetic resolve

and

resources—proof that he is a real poet. And so by the end of the third week of April,

and

after moving on to Margate, Keats will have begun his mythological romance, Endymion. Close to a year later, Keats is finally done with the

4,050-line poem. It will be published as a stand-alone volume, appearing April 1818

(and not

published by the Olliers, but by his new

publishers, Taylor & Hessey). Upon completion, Keats is very glad to have the poem

behind him. All at the same time, the poem acts as a stepping-stone, a trial, a test

of

endurance and commitment, and something to, as it were, get out of his system.

Although the dating is somewhat uncertain, Keats composes two indifferent sonnets

about a

laurel crowing moment: On Receiving a Laurel Crown from

Leigh Hunt and To the Ladies Who Saw Me

Crown’d; Hunt in a way anticipates the idea in a earlier sonnet of his own, To

John Keats,

written on the day—1 December 1816—he publishes an article about Young

Poets

in The Examiner: the poem ends by Hunt writing that he sees a

flowering laurel

on young Keats’s brow,

with the word brow

almost

certainly picking up on its use in Keats’s thus-far most memorable poem, On First

Looking into Chapman’s Homer, which pictures Homer’s legistlating poetic power.

Keats’s dress is, at this point, apparently somewhat non-conventional and offbeat, perhaps signalling a new sense of persona. He sees himself as a cool, young poet—which, of course, is what he is. An open collar is a give-away.