2 December 1816: Leigh Hunt & Publication of On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer

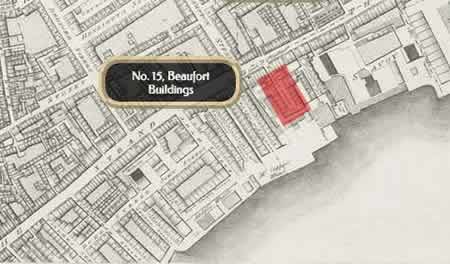

No. 15, Beaufort Buildings, Strand, London

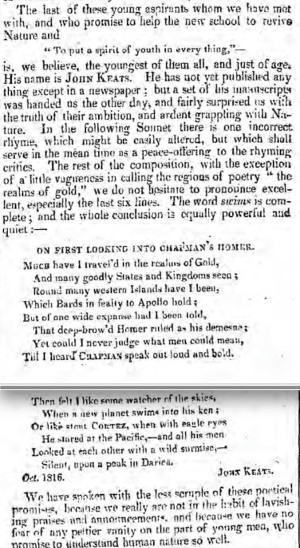

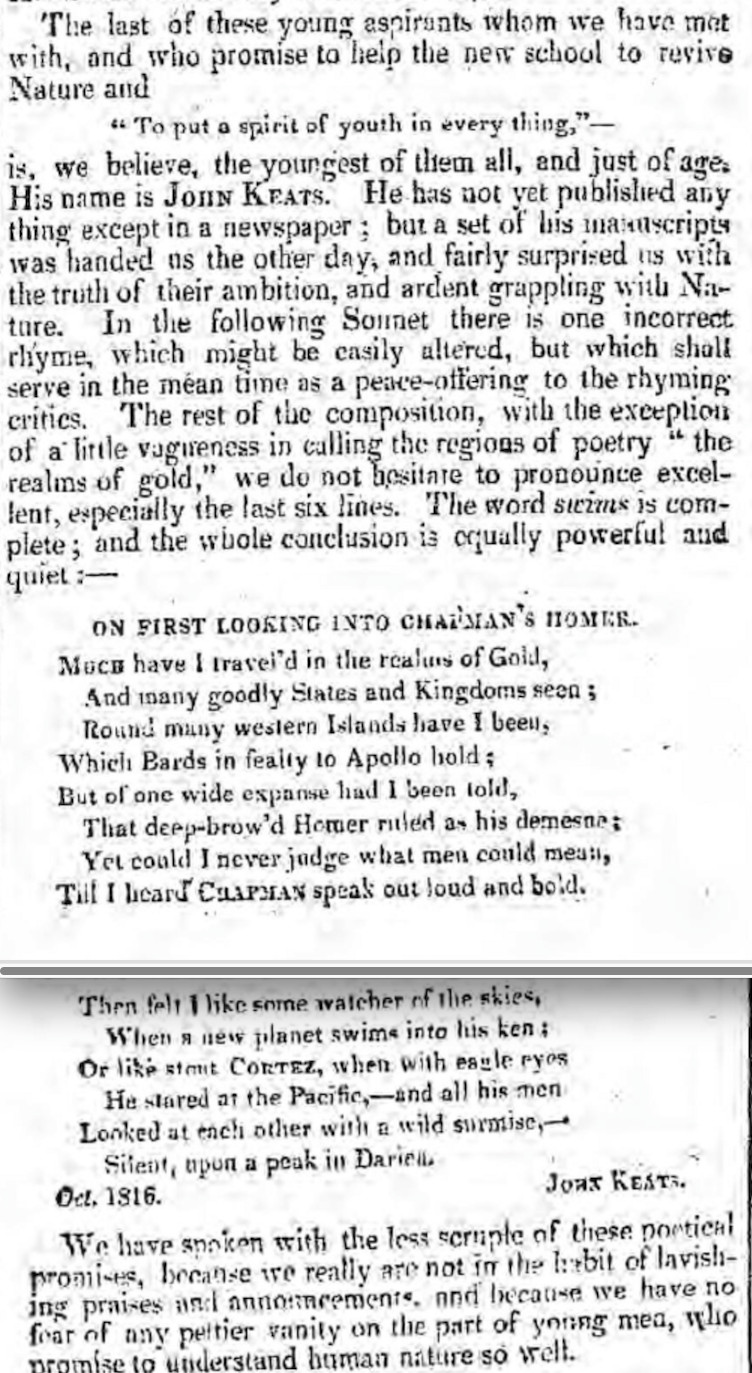

Keats’s sonnet On First Looking into Chapman’s

Homer is published in Leigh Hunt’s

Examiner, along with a short essay by Hunt that names Keats,

Percy Shelley, and John Hamilton Reynolds as Young Poets

of a new school

of poetry

that promises to restore the same love of Nature, and of thinking instead

of mere talking, which formerly rendered us real poets, and not merely versifying

wits, and

bead-rollers of couplets.

Hunt is mildly condescending in his brief discussion of the

three poets. Implicit in his comments (and knowing Hunt) is that these three are,

in effect,

his poetic wards. Referring to Keats’s poem, Hunt, rather teacherly, points to a little

vagueness in Keats’s phrasing, and he also picks out one incorrect rhyme,

but the poem

is judged as excellent; and having seen other poems by Keats, Hunt tells his readers

that they

are surprising in the truth of their ambition, and ardent grappling with Nature.

We can

only imagine that being written about by Hunt in a journal that Keats greatly esteemed

must

have significantly reinforced his poetic ambitions. How could a young, unknown poet

not have

been very excited?

Keats was introduced to Hunt in mid-October 1816 by his friend and first poetic mentor, Charles Cowden Clarke, the son of the head master at the excellent Enfield School, which Keats attended 1803-1811. At this point, in late 1816 and into 1817, Hunt—as poet, publisher, critic, journalist, appreciator of art, and martyr for reformist causes—is for Keats both a model and a hero, having spent two years in jail (February 1813-1815) for slandering the Prince Regent (as, among other things, a liar and libertine). Quite naturally, Hunt takes on the role of guide for Keats’s poetic direction—and formative Keats is, equally understandably, the willing apprentice . . . at least initially. [For more on Keats meeting Hunt, see 9 October 1816.]

But Keats’s sonnet itself: What can be obviously acknowledged is memorable phrasing that captures the drama of imaginative and inspirational discovery. At the same time, however, the poem displays the aspirations of a young, awestruck poet-in-progress—someone on the margins looking with covetous awe at the qualities and achievement of epic poetry, and thus the poem appeals to sentiments of endearment (look how sensitive the young poet is!) and congratulation (good for the young poet!). The poem ends with Cortez/Keats* looking out toward future with wonder, uncertainty, intimidation, and possible (only possible) direction, which exactly captures Keats’s station and situation as a poet at this point in his poetic progress. The poem is a decent allegory of poetic potential.

For his part, Hunt marks the occasion with his own

sonnet to Keats, one which pictures Keats with a flowering laurel

on his brow. Hunt,

too, flatters himself that Keats sees him as possessing senses that discerningly perceive

the loveliness of things.

Hunt’s sonnet is a little self-serving, and might be

translated as, Follow me Keats, and you too will be able to poetically see into all

things—including nature, human nature, and even female form . . .

So, again, this is an important moment for the young and almost completely unknown Keats. With Hunt’s connections and circle of friends, and with Keats’s name now launched in the controversial, free-thinking, and ambitious Examiner, he is quickly introduced into (and associated with) London’s liberal intelligentsia, which expands until, within a year, Keats has met many writers, artists, critics, poets, and publishers, many of whom become unconditionally supportive of Keats’s gifts and potential. Thoughts of a medical career are now moving aside, even with Keats still doing some work at Guy’s Hospital and his listing as certified apothecary appearing this month. [For a flowchart of Keats’s movement into the London cultural intelligentsia, see Keats’s Social Network.]

But for Keats’s poetry to progress, he eventually will have to go beyond Hunt’s sometimes lax poetry of sociability and affected

over-description for its own sake—poetry that often remains (albeit with moments of

stylistic

dexterity) on the surface of the subject. We should not be surprised that Hunt’s poetry

has

not, as they say, withstood the test of time; but we have to remember that Hunt was

not driven

with anything like the same single-mindedness as Keats to be one kind of writer: he’s

a

jack-of-all trades writer, and as much an essayist, reviewer, journalist, critic,

and editor

as he is a poet. As for Keats, models for his poetic development will in not too long

be set:

Keats, increasingly deliberately, and with great effort, will study (among others,

but mainly)

Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, Dante, and Wordsworth, so that he might, calmly and independently,

poetically approximate what he will call the Principle of Beauty

(letters, 9 April

1818). Keats aims for and develops a complex poetic character determined more by deeper

feeling than occasion; with explorative potential rather than defined purpose; and

with

natural sensations rather than well-trodden sentiments.

*Keats happens to make an historical error in the poem. The explorer who stood on a peak to gaze upon the Pacific (in December 1513) was in fact Balboa, not Cortez. Some too-ingenious criticism posits that Keats’s mistake is intentional; but commonsense, and given the early stage of Keats’s poetic career, makes this suggestion rather over-determined. Keats simply gets his explorers mixed up, and none of Keats’s exceedingly well-read friends noticed the error either.