27 June 1804: Keats’s Mother Hastily Remarries; Consumption: the Family Complaint

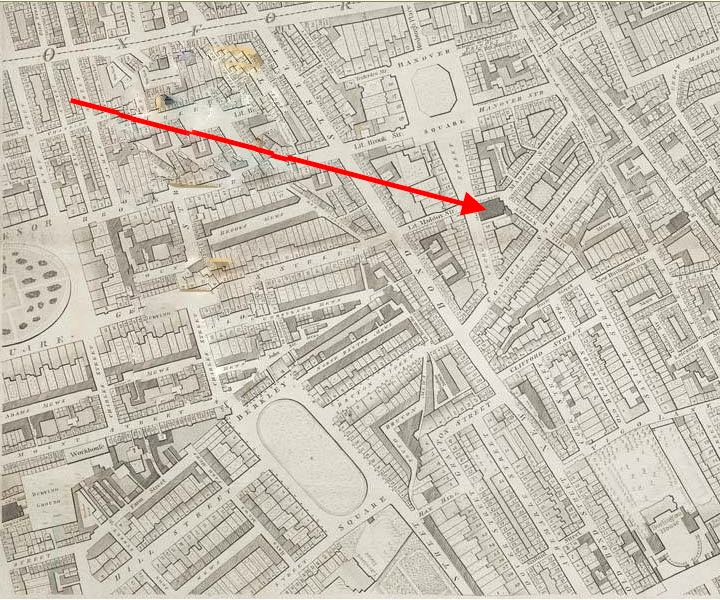

St. George’s Church, Hanover Square, London

Where Keats’s mother, Frances, remarries, 27 June 1804, shortly—very shortly—after the death of her husband. It is the same church that she had married Keats’s father. Given Frances’ unforeseen shirking of parental responsibilities, and out of immediate need, Keats and his siblings go to live with their maternal grandparents—John and Alice Jennings—at Scotland Green, Ponders End, Enfield. With his grandparents, Keats would have been somewhat exposed to a lifestyle that pushed beyond the working class, since John apparently had gourmand aspirations that the eventual trustee of the family estate, Richard Abbey, liked to look down upon out of snobbery.

Frances hasty, unwitnessed marriage is to a somewhat suspicious character, William Rawlings, a young banking clerk. The marriage does not last very long, and Frances may have had developing drinking problems while also temporarily taking up with another dubious character in Enfield, close to where the boys attend school. No doubt this has some chins wagging and would have greatly distressed Frances’ parents, John and Alice. And no doubt this would have, at the very least, and for the moment, confused Keats and his siblings: dad is dead; mom is gone; and what happened to their home?

Unfortunately, grandpa John Jennings will die in March not long after the marriage of Frances and Rawlings, and the Keats family moves again, to Church Street, Edmonton, where grandma Alice will take care of the four children. The will of John Jennings is quite carefully set up to ensure that the fairly significant funds were neither squandered nor placed into the wrong hands, meaning Frances and Rawlings. Frances will end up fighting in court for her share in court, but unsuccessfully.

After eventually moving back with her mother, Alice

Jennings, and further financial and health woes, Frances dies in March 1810 of consumption—tuberculosis. She is

thirty-five years old. Young Keats witnesses this slow, wasting

illness, also known as

the white plague.

Susceptibility to the agonizing, lingering disease is thought to

run in the family, and it ends up killing not just Keats but also his brothers Tom and George. (It may also have caused the death of two other close relatives on the

mother’s side, Thomas Jennings and Midgely John Jennings.) George Keats will quite

rightly

come to refer to consumption as the Family Complaint,

given that, at the time, the

dominant belief is that the illness is inherited. The understanding that consumption

is

extremely infectious does not become proven and accepted until the last decades of

the

century. To put this into historical context, consumption is the greatest cause of

death in

the UK and Europe in the nineteenth century. [For much more on Keats and consumption,

see 3 February 1820.]

Thus Keats’s world—his close family—is fairly narrowed, with the deaths of his father, mother, grandfather, and much beloved grandmother. Little wonder that Keats’s remains very close to his remaining siblings.

As Keats moves into adult life, he says precious little about his mother, and in some ways this absence of expressed memories or strong feelings about her is conspicuous, at least in his letters and poetry: Is there resentment, repression, inarticulate or incomplete love, confusing associations, anxieties—or just something too deep for tears? Most importantly for Keats as a poet, it will take a few years of writing for him to poetically explore mortality and suffering in deep, complex, and accomplished ways, and this exploration is an important piece in Keats’s poetic development. We only know that young John Keats suffered for an extended period with the loss of his mother, and it may have turned him toward the imaginative world that books and poetry offered—but this, perhaps, is to romanticize the nature of poetic drive and genius.