25 January 1821: This Dreary Point

; A Man Governed by Imagination &

Feeling

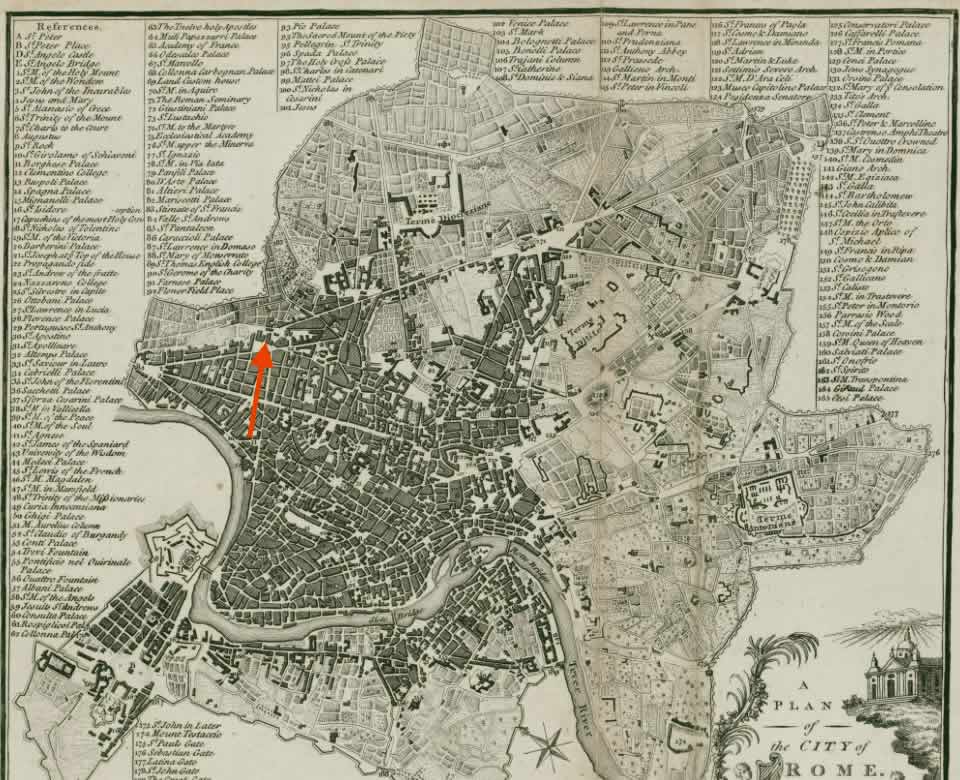

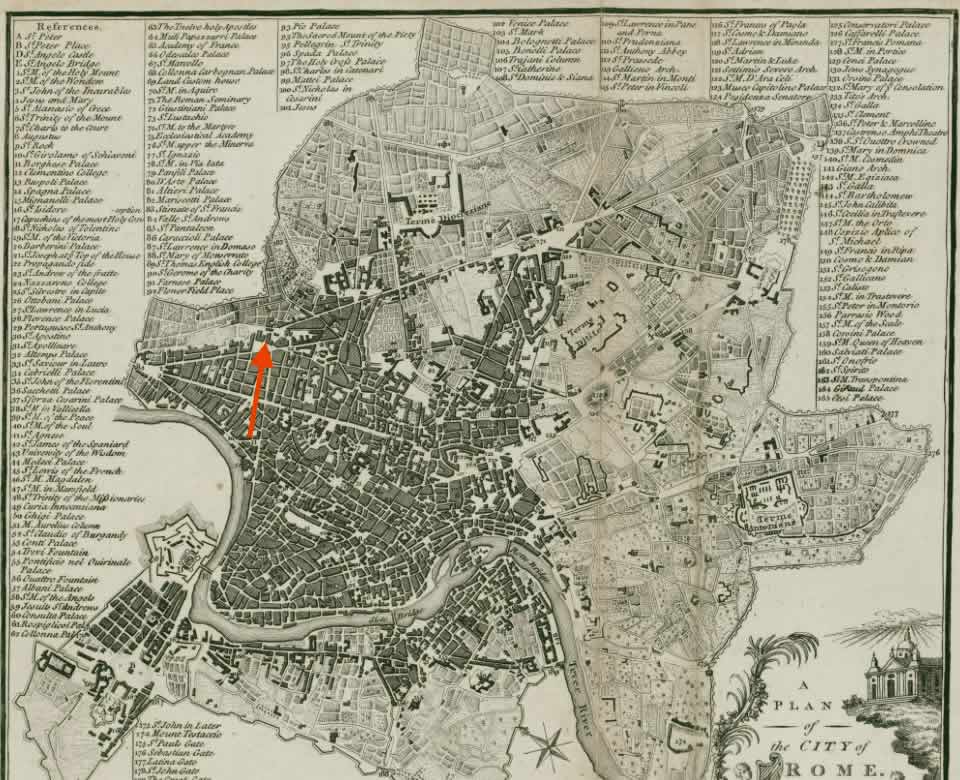

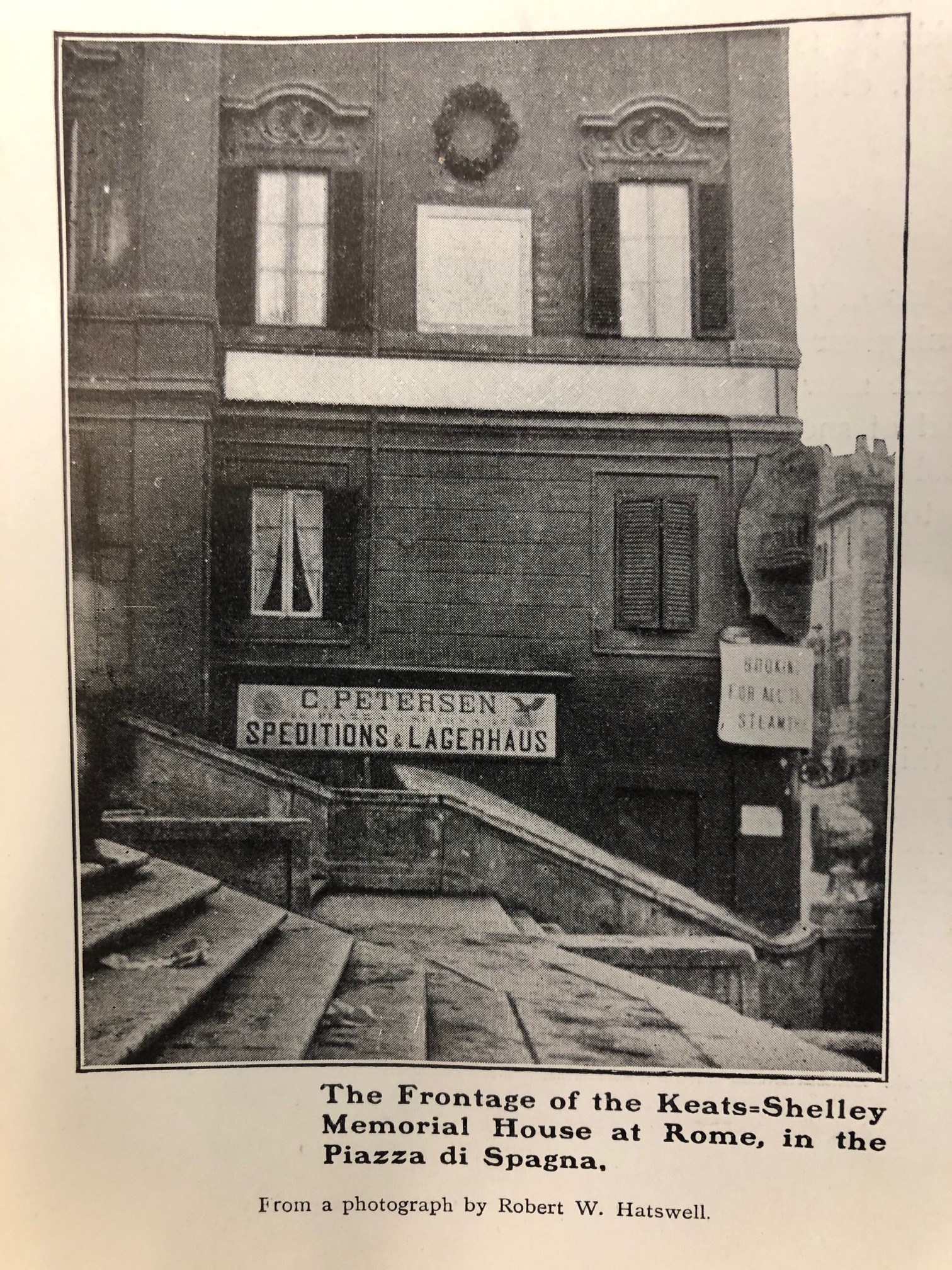

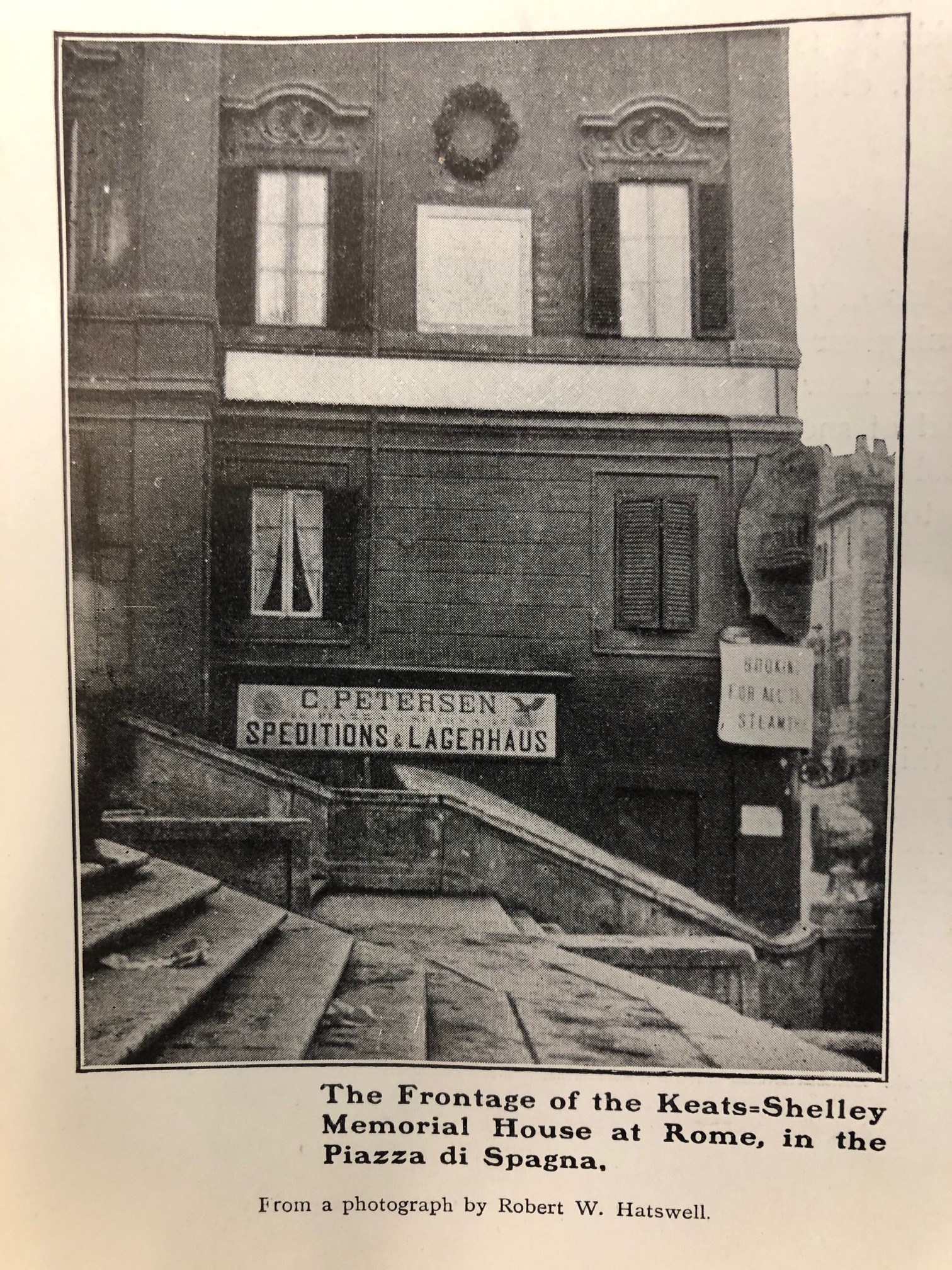

26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome

Keats and his good friend Joseph Severn are in rooms at 26 Piazza di Spagna, Rome, arranged by Keats’s physician, Dr. James Clarke, who is also in Rome and very close by.

Keats, twenty-five years old, has been in Rome for not quite two months, having begun

his

voyage from England mid-September 1820, though initially slowed by bad weather and

then

quarantined in Naples. This trip from England to Italy’s warmer weather is solely

motivated

with the hope to restore Keats’s health, though even before he leaves England it is

apparent

to both him and his closest friends that he suffers with the most prevalent illness

of the

era, consumption—so named because the illness slowly consumes

an individual, and for

reasons not then understood. (It will take more than another fifty years for consumption

[tuberculosis] to be understood as the highly infectious white plague

that even today

remains a deadly, widespread disease in parts of the world.)

Severn watches over and nurses Keats for almost every moment since Keats’s departure from London. This is about the same amount of time that Keats watches over the decline and death of his younger brother, Tom, also from consumption, September to December 1818. Keats, then, knows what is likely to come, and for almost a year he has intimations that he is doomed by the terrible illness. We have to picture Severn carrying gaunt, pained Keats to the sitting-room from the bedroom and dressing him in clean clothes. Sadly, Keats is to some degree calmed, knowing that he has no hope. What has come to agitate Keats is Severn’s refusal to give him access to a bottle of opium so that he might kill himself. Severn is held captive by Keats, who, in utter fear, does not want Severn out of his sight; he does not want to die alone. At the end of his own life, almost sixty years later, Severn continues to express how he is haunted by Keats’s influence, as if he too does not want to die alone; he wants, and gets, his grave beside that of Keats. They are fashioned as twin graves.

By now, January 1821, Keats’s state is completely hopeless. His stomach and lungs

are fully

compromised. He can no longer digest food, and he constantly coughs up large amounts

blood-streaked fluids—clay-like expectoration,

Severn graphically describes it (25/26 Jan). His

body is in constant fever as it vainly attempts to fight the illness, while it also

craves

nourishment it cannot digest. Keats’s emotional state is, understandably, equally

strained:

both Severn and Clarke comment on Keats’s overwrought mind,

which they

causally couple with his physical illness. On 3 January, Clarke notes Keats’s state

of lung

and stomach degeneration, but also, now knowing Keats a little, he adds, I fear he has long

been governed by his imagination & feelings.

Keats certainly has, but it is striking

that Clarke, with his excused ignorance of how tuberculosis is contracted, ties the

presence

of the illness to what is most striking about Keats, and the kind of disposition that

likely

turns Keats to poetry in the first instance.

On 25/26 January, Severn writes to Keats’s very

good friend and publisher, John Taylor. Severn,

echoing Clarke, theorizes about Keats’s intense

feeling

and passions of mind.

Having passed countless hours listening to Keats

unburden himself from his deathbed about parts of his life

and various changes,

Severn attempts to describe Keats’s nature.

He concludes that Keats has lived intensely

without a sustaining calm of mind.

Severn suggests that this unrelieved, restless

ferment

in Keats’s emotions

and sensations

has brought him to this

dreary point.

(Severn writes sensations

twice in one sentence but replaces one of

them with emotions.

) Once more, Keats’s base character, his illness, and his vocation

of poetry are intertwined. But at this point there is only one real comforting thought

for

Keats himself: that soon he will soon die.

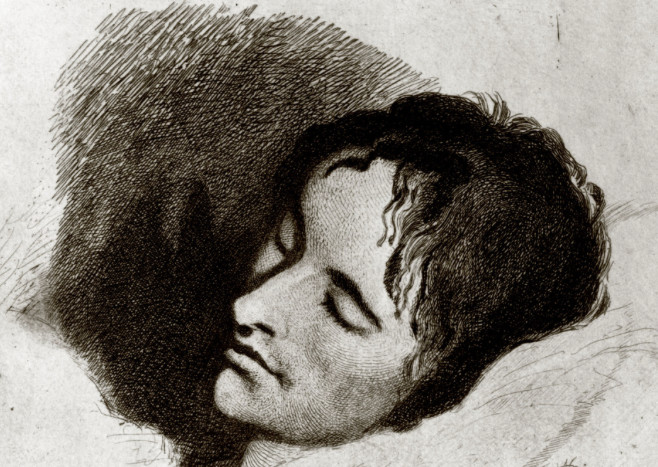

a deadly sweat…(Keats-Shelley House, Rome)

The terms of Severn’s insights are, though,

helpful: the balance of intensity in feeling and sensation through reflection is what

Keats

himself first points to in his poetics as requisite to great poetry. Back in late

1817, as

Keats begins to formulate the direction and character of his poetic progress, he conceives

that truth and beauty can be capably interlinked and are indistinguishable through

acts of

empathetic imagination—acts that, Keats notes, would ideally exist partly on sensation

[and] partly on thought.

This, Keats believes, is something like the position that William Wordsworth’s philosophic Mind

holds, and the poetical depth to which Keats aspires (to Bailey, 22 Nov. 1817). Poetic success comes when Keats manages to achieve or balance

a poetry of sensation without over-reaching emotions, and a poetry of thought without

a

palpable design upon us

: a poetry of poised, unobtrusive

intensity (3 Feb 1818).

Poetry,

Keats will write in anticipation of his greatest work of 1819, should

surprise by a fine excess and not by Singularity

(27 Feb 1818).

The balance that Keats strives to achieve in his poetry is, then, in some ways, tied

to the

balance he seems to have fought for in his life—a story mainly to be gleaned from

his letters.

In his poetry, Keats ultimately succeeds; but life, unlike poetry, is hardly perfectible,

and

is inconstant in its passing; poetry can offer or at least represent lasting perfections

and

constancies that life cannot offer, and much of Keats’s best poetry—on, for example,

the

unknowable story a timeless urn can tell; the fading but never-faded song of a nightingale;

a

season held still by its untroubled harmony; an ailing yet enraptured knight-poet

forever on a

cold hill side after experiencing a beautiful fate—addresses this condition and tension.

This

controlled intensity may be Keats’s enduring achievement as a poet, but as a person,

such deep

equipoise in the face of uncertainty was something that came and went from him—and

in the end,

he agonized over lost love and the meaning his experience—in one of his last known

letters, he

writes, we cannot be created for this kind of suffering

(to Brown, 30 Sept 1820). The

meaning of human suffering struggles to be resolved in the face of passing time or

by the idea

of meaningful afflictions, but the power of the capable human imagination can at least

render

this irresolution, as forms of both beauty and profitable uncertainty, not just for

one

passing moment, but for all moments to come.