26 June 1820: Greatest Things at a Bad Time: Keats’s 1820 Collection as Last Trial

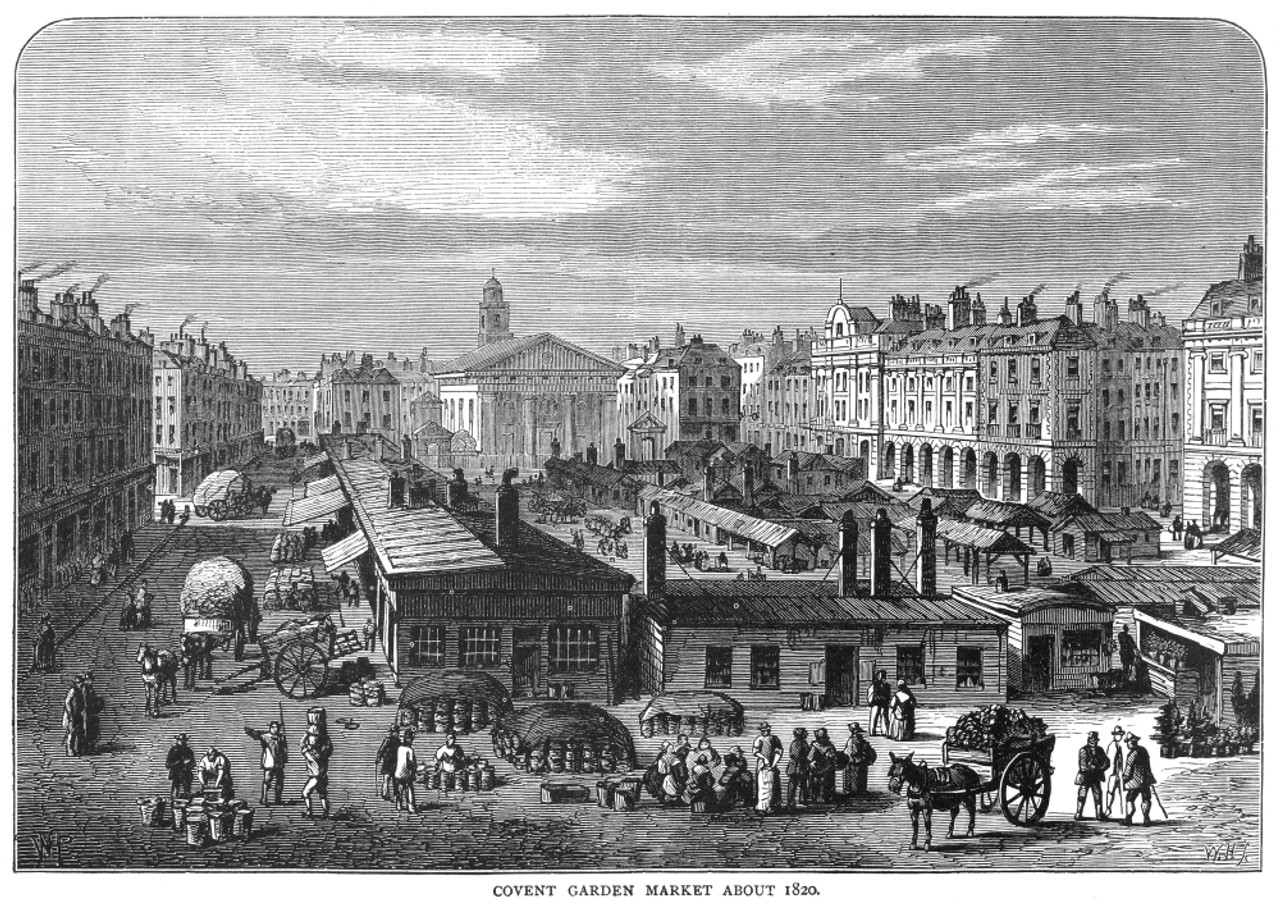

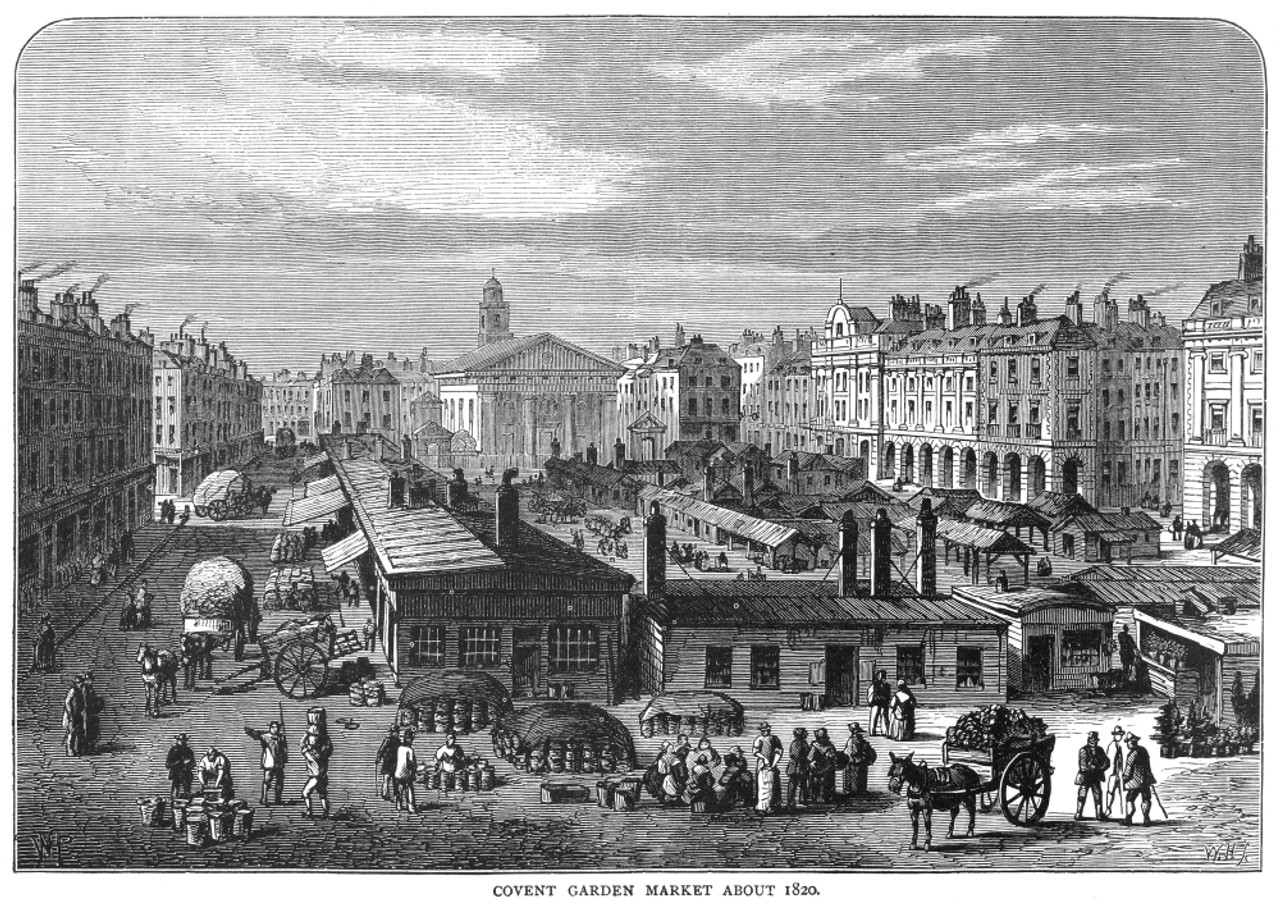

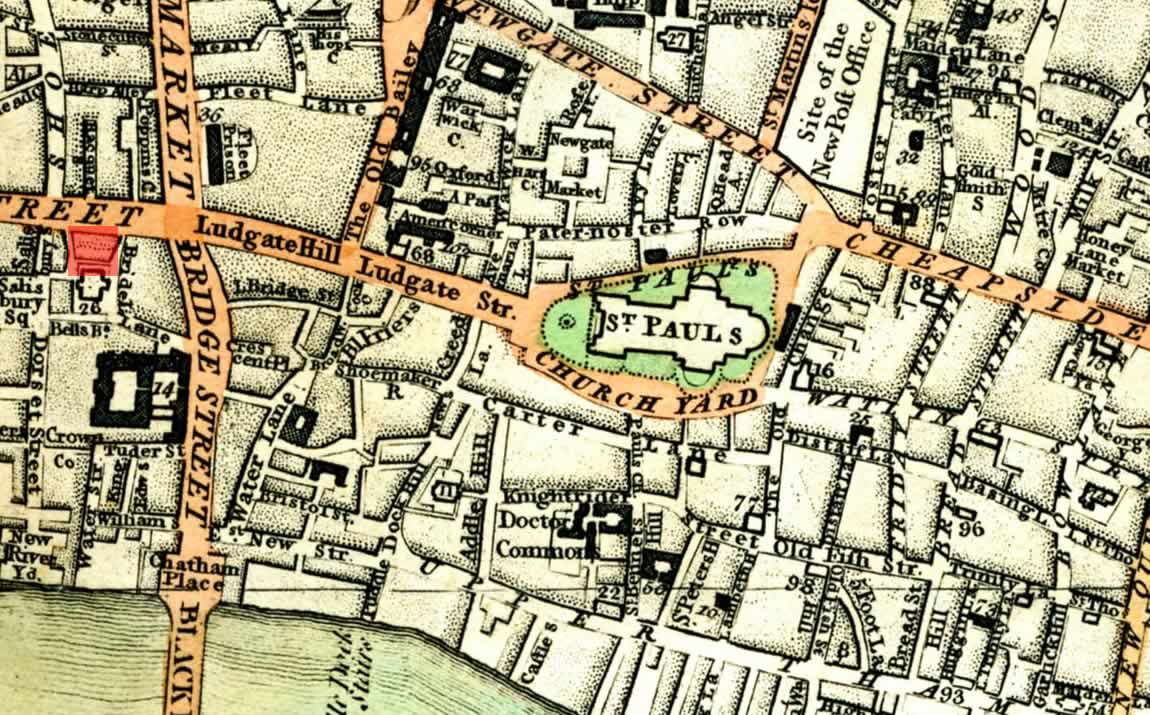

93 Fleet Street, London

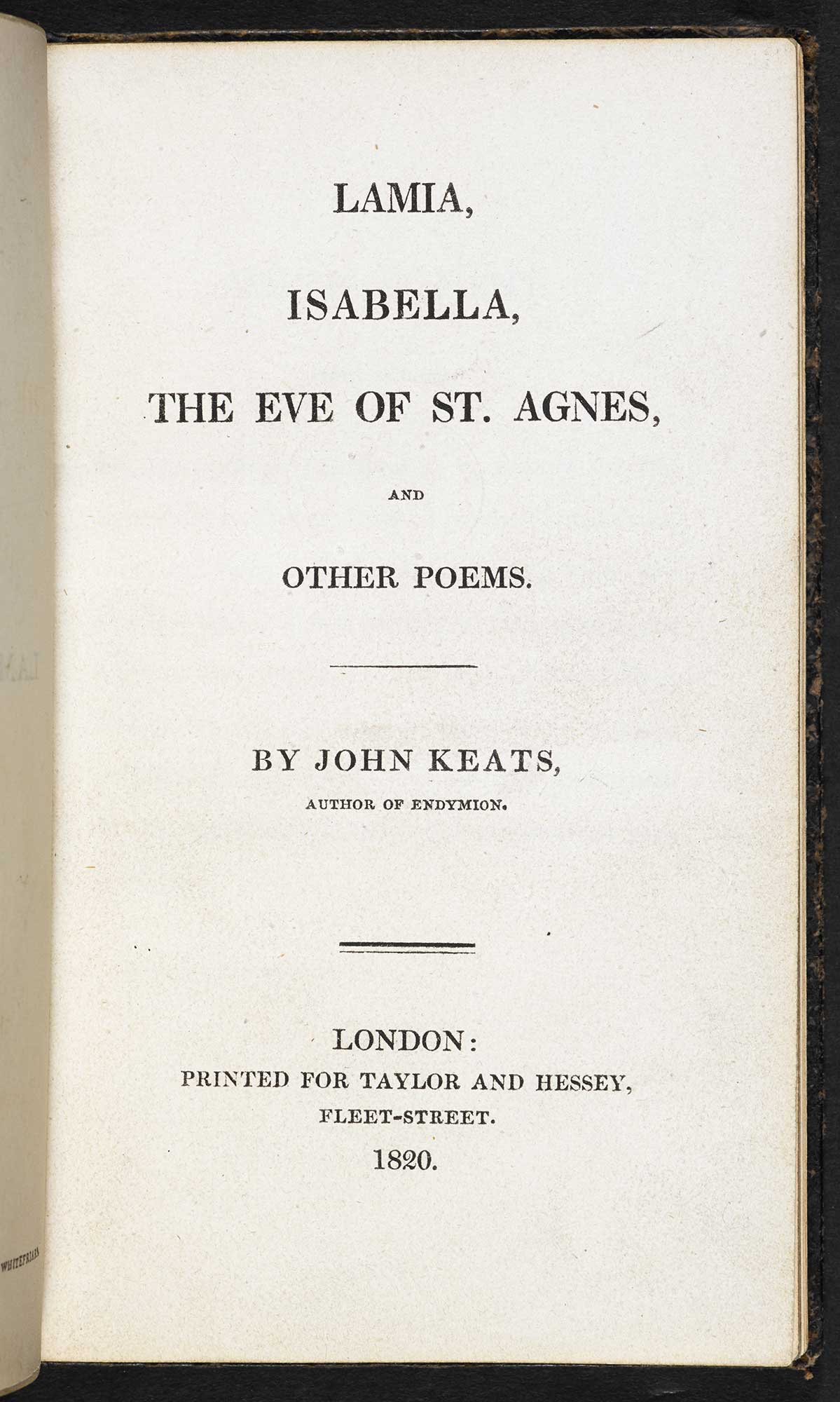

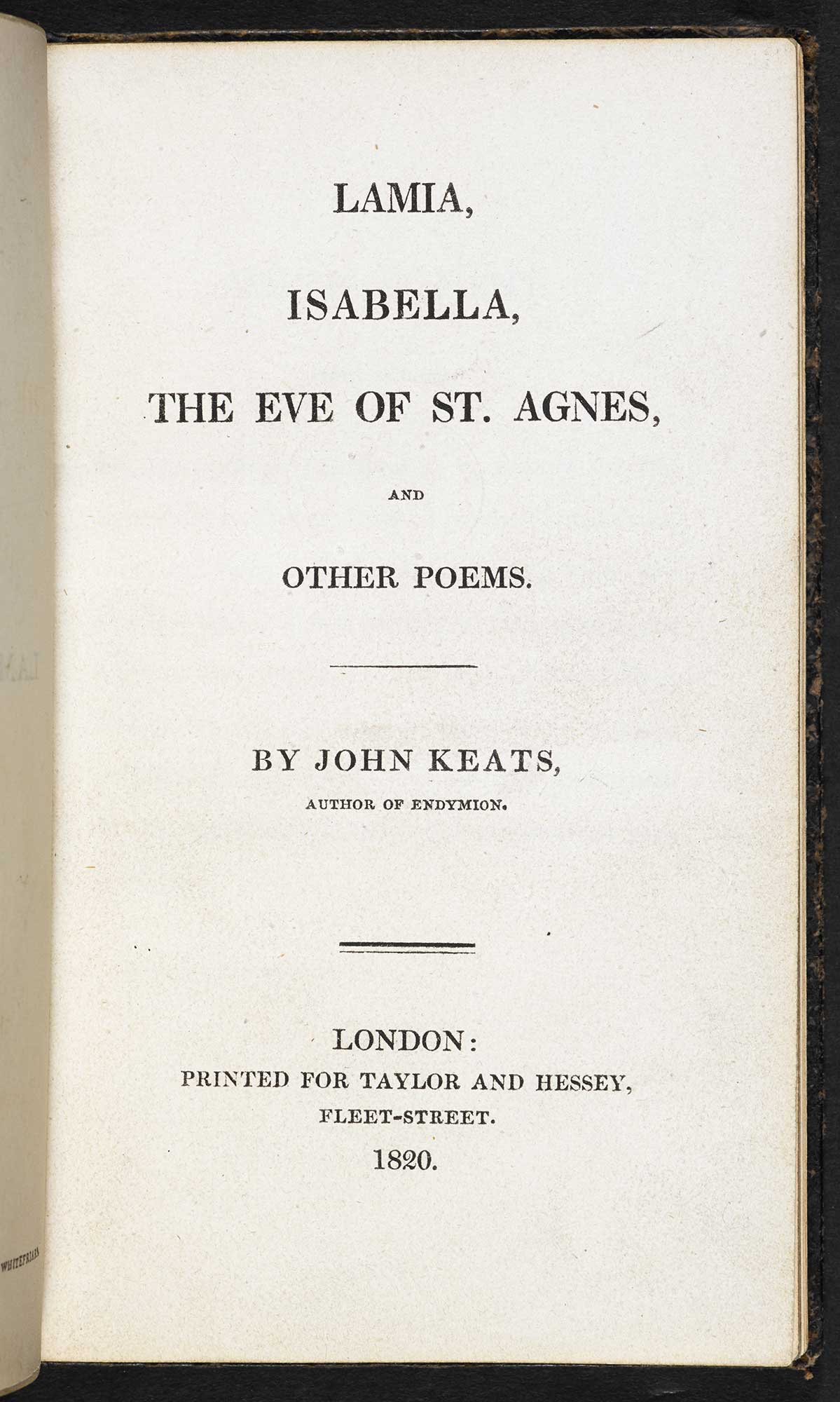

The offices of Taylor & Hessey, publishers and booksellers. On 26 June 1820, Taylor & Hessey announce publication of Keats’s third and final volume of poetry, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems. The book itself is probably available about a week after the announcement (in advance copies, at least), though it is advertised as forthcoming as late as the end of July. (Official publication date is often given as 1 July.) Taylor & Hessey previously publish Keats’s epic romance Endymion (1818), and they also assume rights over Keats’s first volume, Poems (1817), first printed (on commission) by another publisher. Both John Taylor and James Hessey are good friends with and supporters of Keats, and they have a number of mutual friends. Taylor is especially generous in helping Keats financially.

In the last week of June, just after Keats has been generously taken into the Hunt household after attacks of blood spitting, Keats,

in worrisome physical health and in an uneven emotional state, writes to his very

good friend,

Charles Brown; the volume, he writes, is to be

published: My book is coming out with very low hopes, though not spirits on my part. This

shall be my last trial; not succeeding, I shall try what I can do in the Apothecary

line.

Keats had been medically certified in December 1816, at almost exactly the same

moment he decides to dedicate himself to poetry and to poetry alone. In now writing

that he

might return to his medical training in order to make a living, Keats is hoping against

hope,

since one part of him is aware that his physical condition (clear signs of consumption)

is

extremely precarious.

The misfortune should not be lost upon us: Keats’s remarkable collection appears at the moment as those terrible indicators confirm full-blown consumption.

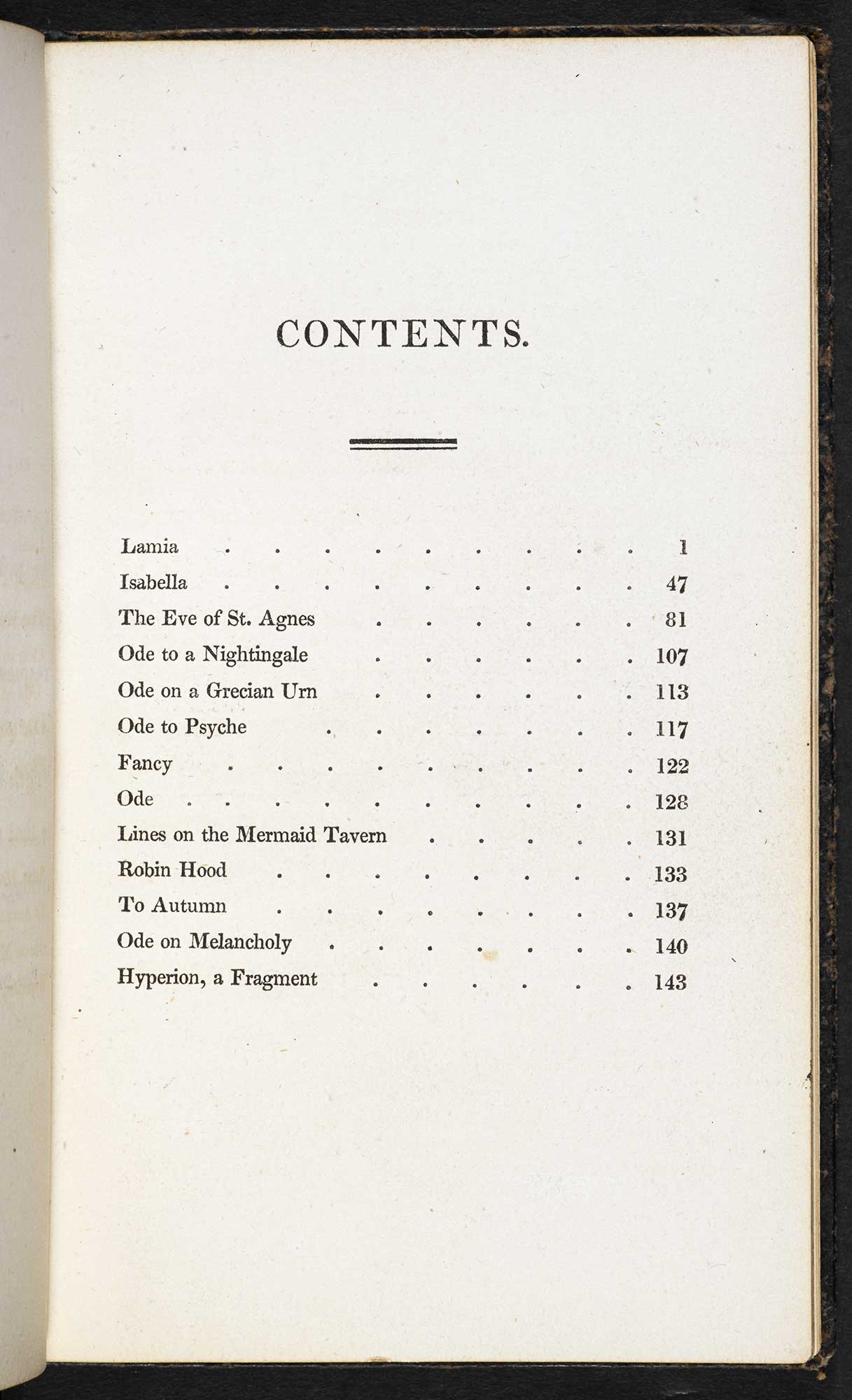

Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems is one the strongest collections of poetry ever published in the English canon. Keats puts into practice ideas and poetic theories he has been developing in his letters since, approximately, late 1817—in, that is, an epistolary poetics worked out and articulated to his friends and family. And, along with the poetry itself, these letters constitute the complementary measure of Keats’s pace of thinking: the complex striving in his developing thoughts about poetry and the kind of poet he strives to become. Keats, though, never writes a formal defense of poetry. His only public comment on his own poetry is to make a cringe-worthy apology for the relative immaturity of his second volume, Endymion.

To expand a little: Keats’s poetics expressed his letters anticipate and define his best work. That is, he formulates the qualities of great poetry and the kind of poetry he wants to write in advance of actually composing his best work. This is noteworthy inasmuch as it points to Keats’s clear dedication to his poetic development; in fact, a fair amount of earliest poetry is about poetic development. Further, there is no post-hoc commentary on the nature of his work, which artists are sometimes fond of formulating. And so Keats’s own evolving terms and theories remain the most critically profitable ways into his poetry—for example, the imagination as a form of knowing; beauty as its own form of truth; the balance of sensation and thought; fine excess; the commingling of joy and sorrow; the necessity of passivity and receptiveness; unobtrusive poetry; the camelion poet; the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime; the empathetic imagination; knowledge as sorrow; the weight of human suffering; poetic self-possession; measured intensity; disinterestedness; negative capability; the eternal principle of beauty; the address to long history rather than short time.

For this 1820 volume, then, there is no author’s preface, though Keats could have

drawn much

of it right out of his letters and in some of those subjects listed above. Keats writes

to his

very good friend Charles Brown that his only

desire

is to be remembered

(13 March 1820). That desire quite obviously

becomes true in ways that Keats partly anticipates. As he writes in October 1818,

I think I

shall be among the English Poets after my death.

This is a particularly astonishing

statement in that Keats, at the time, is fully aware that his first two volumes are

largely

ineffectual; he has not yet written anything close to the quality of his 1819 poetry.

Keats is unhappy about the inclusion of the fragment Hyperion

in the collection: an Advertisement

at the beginning of the volume, added somewhat

apologetically by the publishers, claims Hyperion is a fragment

because the reception given to that work [Endymion] discouraged the author from

proceeding.

In an existing copy of the volume, Keats, obviously frustrated, crosses this

out and writes, This is a lie!

Keats claims it was illness

that prevented

completion, yet even this might not provide an exact reason for leaving the poem incomplete,

since the poem’s style and plot (perhaps in too many ways derived from Milton) seems

to have

stymied Keats, or at least it felt unnatural. In the end, though, Keats must have

been torn,

since at moments he believed that a long poem represents the premier poetic achievement,

and

Keats’s ideas about the power, range, and importance of art simmers in his two attempts

to

render the Hyperion story. That said, Hyperion becomes, and

remains, greatly respected.

Keats’s last attempt with the story, known as The Fall of Hyperion, was begun in July 1819. His enthusiasm seems to have completely faded a few months later, despite infusions of Dante-esque moments that vary the poem’s imagistic reaches, while at the same time Keats drops some of Hyperion’s Miltonic stylistic manners; but no doubt the later story’s complexities, now using a first-person narrator, more subtly challenge larger ideas of, for example, vision and dream—and the poet figure’s uncertain rise to imaginative capabilities in the face of suffering. Yet despite this, and though some of this underpinning theme underwrites Keats’s very best poetry, Keats seems unable to conceptually manage the poem. A marvelous, substantial fragment it is.

The poetry in the collection moves very far from what characterizes much of Keats’s earlier work: the poetry of occasion; epistolary modes; purposes of entertainment and a sense of sociability; poetry of sentimental affect; writing that often obsesses over fame; and Keats’s sometimes embarrassing desire to be an enduring poet. Many of these early characteristics reflect relative immaturity, but too often they also tether Keats to the influence of Leigh Hunt, who, in 1816, begins to introduce

A View of St. Dunstan’s Church, Fleet Street,c.1812

Keats into an intellectual and social network that supports, nurtures, and challenges his poetic progress. And now, it is Hunt who, about three-and-and-half years later, generously takes Keats in after Keats seriously hemorrhages during the third week of the month.

Keats’s last and only truly mature phase of work, more or less the first three-quarters of 1819, shows that, through deliberate study, he has come to critical terms with his self-consciously acquired precursors: in particular, Shakespeare’s imaginatively-capable and complex empathy; Wordsworth’s quiet yet searching depth of feeling that conflates with thought; and Milton’s powerful, intense tone as well as the ability to achieve dramatic control through description. He has also found forms that, at least in his lyrical styles (his odes, primarily), feel both natural and, importantly for him, English.

The first half of 1820 is dominated by Keats’s dire financial state, his failing health,

and

his conflicted yet passionate feelings for Fanny

Brawne, which begin to move unpredictably between jealousy, passionate love, and

inevitable loss. Keats is also worried about where he should—or even can—live. By

the first

week of July, as he considers going to Italy in an attempt to restore his health,

Keats is

even more uneven in his thoughts about Fanny, especially when he imagines what he

perceives as

her flirting with, arguably, his best friend (and the person generously keeping Keats

financially afloat at the moment), Charles Brown.

Keats writes he is tormented and in agony thinking about Fanny—he tells her she is

an

object intensely desirable,

and he pleads by the blood of that Christ

that she

not tell him anything she has done that might pain him (like partying or dancing),

since he

would rather die. He adds, I cannot live without you, and not only you but chaste you;

virtuous you.

Sadly irrational and controlling, Keats’s struggling emotional

state is all too apparent.

Somewhat ironically, Percy Shelley, fellow

poet, acquaintance, and defender of Keats, upon hearing of Keats’s illness in July

1820 (and

referring to what he hears about Keats’s consumptive appearance

and weak lungs

),

generously and with generous hope invites Keats to take up your residence with us

in

Pisa, Italy. He also tells Keats, I feel persuaded that you are capable of the greatest

things, so you but will.

Keats will refuse the kindness.

Two years later, after a

fatal (and completely avoidable) sailing accident in his own boat, the badly decomposed

body

of Shelley, aged twenty-nine, washes up the shore in the Gulf of Spezia, Italy. A

waterlogged

copy of the Keats 1820 volume is found crammed into his pocket. Shelley may, at that

very

moment of facing his own death, have been reading those greatest things

of which Keats

was capable. This is somehow beyond being perfectly, poetically, and tragically fitting:

two

poets, in death, in a passing moment of poetic possession of each other, but whose

poetry has

so clearly lived beyond the passing moment. [For more on Shelley and his death, see

16 August 1820.]