5 November 1819: Hazlitt, Keats’s Poetic Development, & a Low-Spirited Muse

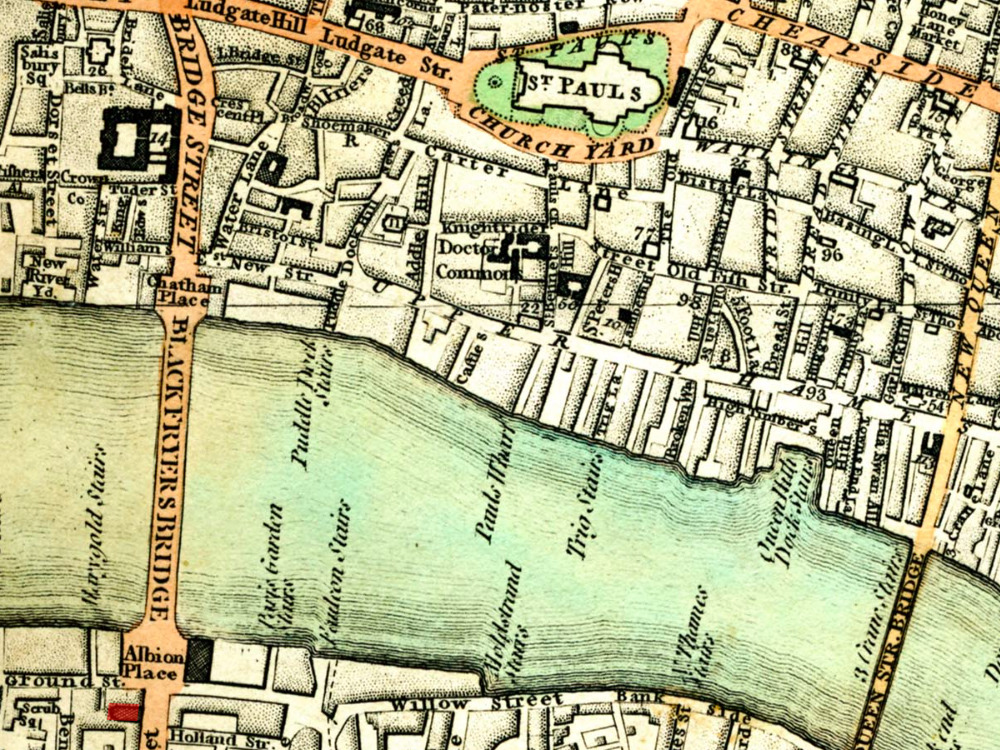

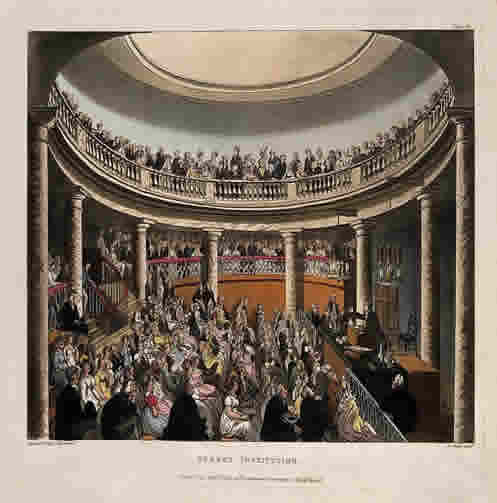

Surrey Institution, Blackfriars Road, London

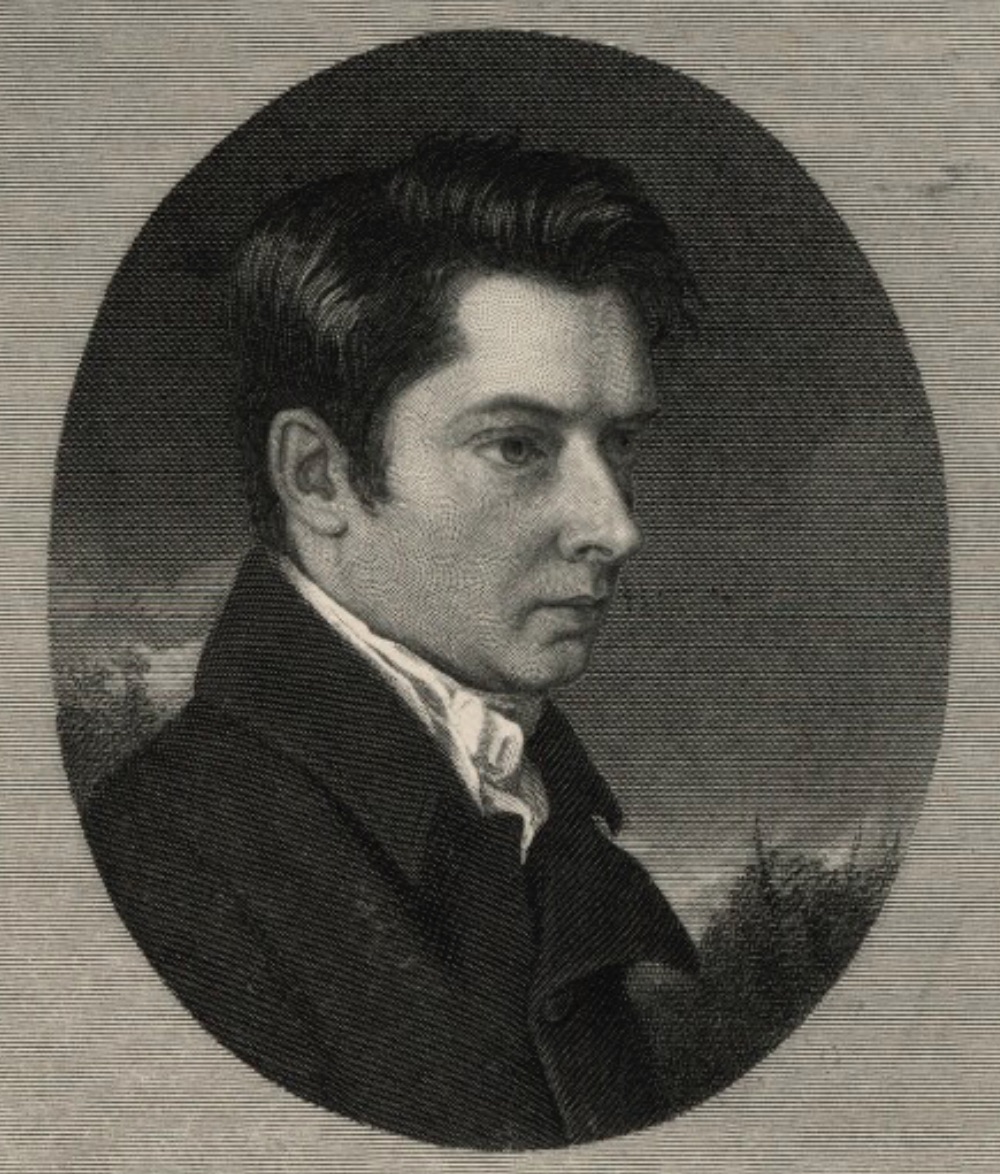

William Hazlitt, the famous literary critic, essayist, sometimes painter, and friend of Keats, misquotes a bit of Keats’s poetry in the first of his eight Friday-night lectures (on Elizabethan drama) at the Surrey Institution, 5 November 1819. Keats is not present. The Surrey Institution is in the building that formerly housed the Leverian (or Lever) Museum, which, by all accounts, was an astonishing collection (including items collected by Captain James Cook on his voyages), before it was auctioned off in individual lots in 1806.

In his development as a poet, Keats, who has just turned twenty-four, greatly admires

and is

influenced by Hazlitt’s theories, insights, and

opinions. As Keats writes, Hazlitt’s depth of taste

is one of the three things to

rejoice at in the Age

(letters, 10 Jan 1818). No doubt mutual admiration exists between

the two, though at the time Hazlitt’s cultural placement is highly established and

Keats’s

quite minor; Hazlitt is also seventeen years Keats’s senior. Culturally, Hazlitt and

Keats are

also joined inasmuch as they are both perceived as Cockney

writers under the spell of

poet, critic, and celebrity journalist, Leigh Hunt,

co-publisher of The Examiner. Also, Keats, like others,

would have been impressed how Hazlitt, in his writing and thinking, moves easily and

inventively between, for example, the vernacular and the genteel, between popular

culture and

high theory, commingling disarming personal insights with challenging grand conclusions.

For

Keats, there was much to admire and learn from.

There is something about Keats that others—often older, more experienced, and more recognized figures—see in the younger poet that leads them to seek out, support, and enjoy his company. No doubt they recognize and are attracted to his remarkable intelligence, his dedication to poetry, his significant potential, and his quietly engaging and often witty nature. Keats was, it seems, generally easy to be with, even if he did have moments and shorter periods of anxiety and depression. Keats’s sensitivity about his own feelings sometimes makes us want to amplify them with modern sensibilities (what isn’t a disorder?), and in particular what seems to be our need to pathologize. Yes, Keats sometimes felt much anxiety; yes, sometimes he felt depressed; and, given his temperment, Keats was both sensitive to and interested in such states.

Important for Keats’s poetic progress—and by early 1818, and to a large degree through

Hazlitt—Keats begins to understand how William Wordsworth’s style of poetry is figured

and overdetermined by subjectivity and self-expression; the selfless, controlled expression

of

the Elizabethans may be closer to his own developing artistic disposition. As Keats

says,

fine excess

is preferable to poetry that leaves the reader breathless

(letters, 27 Feb 1818) or poetry that wears polemic and purpose too heavily. Much

of 1818 is

spent trying to find that controlled, intensive, and empathetic voice, and by early

1819 he

fully manifests it. Hazlitt’s analysis of Shakespeare’s imaginative qualities also greatly influences what Keats strives

toward—in particular, Shakespeare’s genius in empathetically absorbing what subjects

and

characters he seizes upon. The subject is all; the poet is the vessel; the imagination

is the

means; beauty is the goal and the only meaningful truth.

Keats attends many of Hazlitt’s early lectures

on literary matters (Lectures on the English Poets,

January-February 1818), and also

meets personally with him on a number of occasions. Hazlitt is acquainted with Keats’s

poetry

as early as February 1816, when Hunt shows him some

of Keats’s very early poetry at a dinner party. The young poet Percy Shelley is also at the dinner, as is William Godwin, the famous social philosopher and novelist (and

Shelley’s father-in-law). This looks toward Keats’s intellectual, artistic, and social

network

to come in late 1816 and into 1817, mainly through Hunt, who sees himself as the guiding

influence upon young, green Keats, and which Keats initially was willing to embrace.

But,

after getting to know Hunt and his poetic inclinations better, as well as expanding

his

reading and circle of personal friends, it does not take long for Keats to deliberately

seek

independence. Why pay attention to Hunt’s The Story of Rimini

when you can study and parse Paradise Lost and Shakespeare’s plays, as well as attempt to come

to terms with the nature of Wordsworth’s

poetic accomplishment?

In terms of inspiration and accomplishment, November 1819 finds Keats (in his own

words)

so very lax, unemployed, unmeridian’d, and objectless these last two months that I

even

grudge indulging [. . .] myself going to Hazlitt’s Lecture

(letters, 10 Nov). Keats expresses to his brother and wife in

America that Nothing could have in all its circumstances fallen out worse for me

than the last year has done, or could be more damping to my poetical talent

(letters, 12

Nov). No doubt Keats is thinking not only about the indifferent response his poetry

has thus

far received, but also about the death of his younger brother, Tom, whom Keats nurses for a few months as Tom sinks to a slow,

agonizing death on 1 December 1818.

To his publisher and friend John Taylor, Keats

confesses that, in terms of his writing career, he now seldom feels ambitious

—his

Muse,

he writes, is low-spirited.

Nevertheless, he is determined to publish

a poem before long and that I hope to make a fine one,

and that if he can muster some

creative nerve, his greatest ambition

will be to write a few fine Plays

(letters, 17 Nov). He writes that he does not want to publish any of his recent poetry,

which

is something of a surprise given what he writes in 1819; thankfully, he goes back

on this.

Although this month he does some writing (King Stephen and work

on The

Jealousies; or, The Cap and Bells), including, perhaps, some tinkering with The Fall of Hyperion, at this point his

best work is behind him.

Even more than usual, Keats’s energies this month are spent on financial matters, and he spends much time in the city. He needs money very badly. And his brother George (who has more or less gone bankrupt in America after investing in a boat that sinks) also needs to re-finance his business ventures, and Keats is trying to help him out. Assets in the family inheritance overseen by the trustee Richard Abbey are not yet clear of an apparent though fuzzy legal suit; moreover, the stock market is low, and selling stocks to realize cash from the trust is, in Abbey’s view, a very bad idea (letters, 12 Nov). Keats seems not to have received any money from Abbey for a number of months; Keats may have exhausted what capital was his by living on credit based on those funds (loaning money to others has not helped, either). Abbey suggests that Keats take up the bookseller business, which Keats dismisses; the following month Abbey suggests that Keats join the tea brokerage business, which likewise does not inspire Keats, though he is slightly interested, given that he imagines that he might make some money without having to work too hard. What is clear, though, is that Keats feels greatly pressured to make a living. What he is not aware of is that he had enough money to see him through a few years—if only he knew about it. That is, he did not know that a further 800 pounds or so of family money was held by the court; George did not know either; and it appears Abbey may also have been unaware of the funds, though in his duty as family trustee, he probably should have known about the money despite it being in a legal limbo.

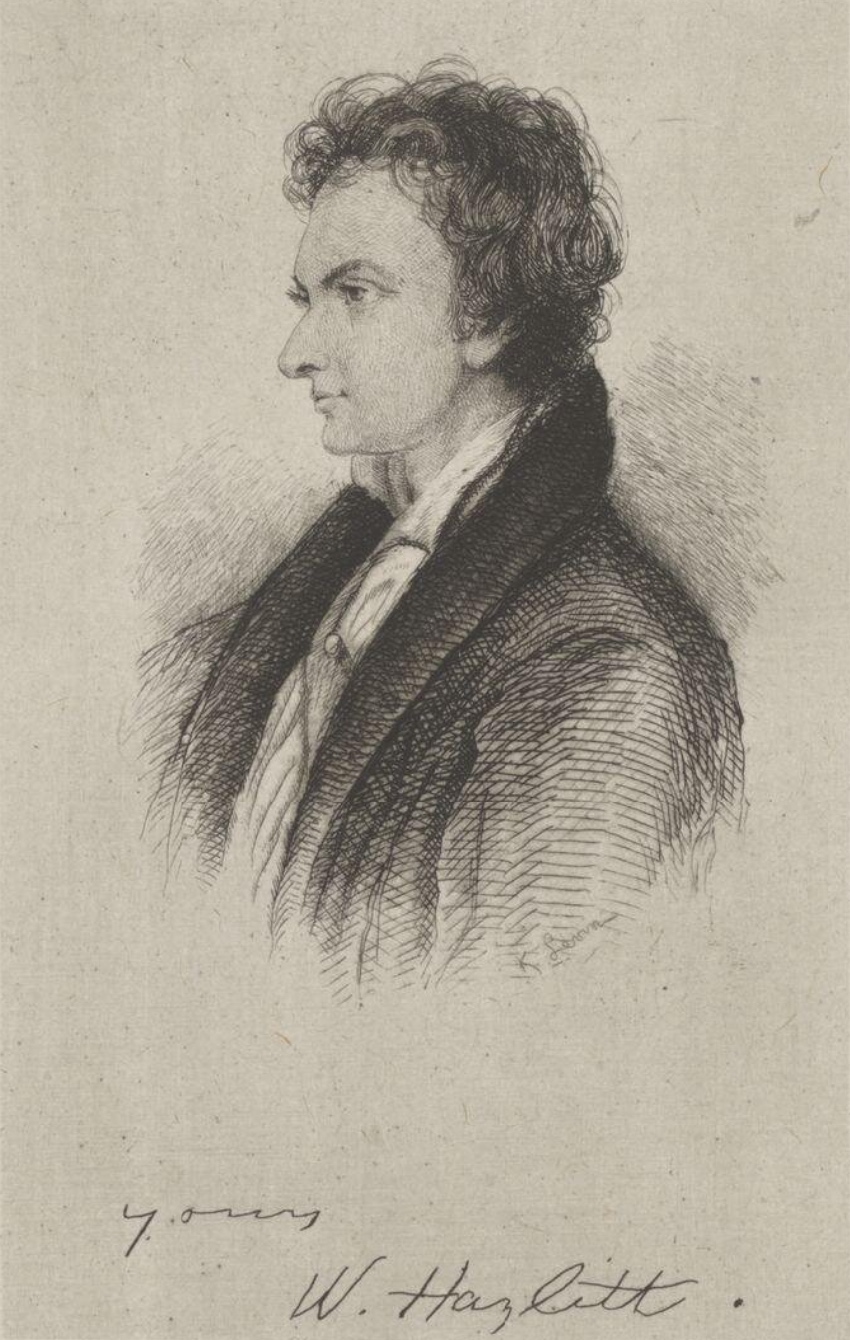

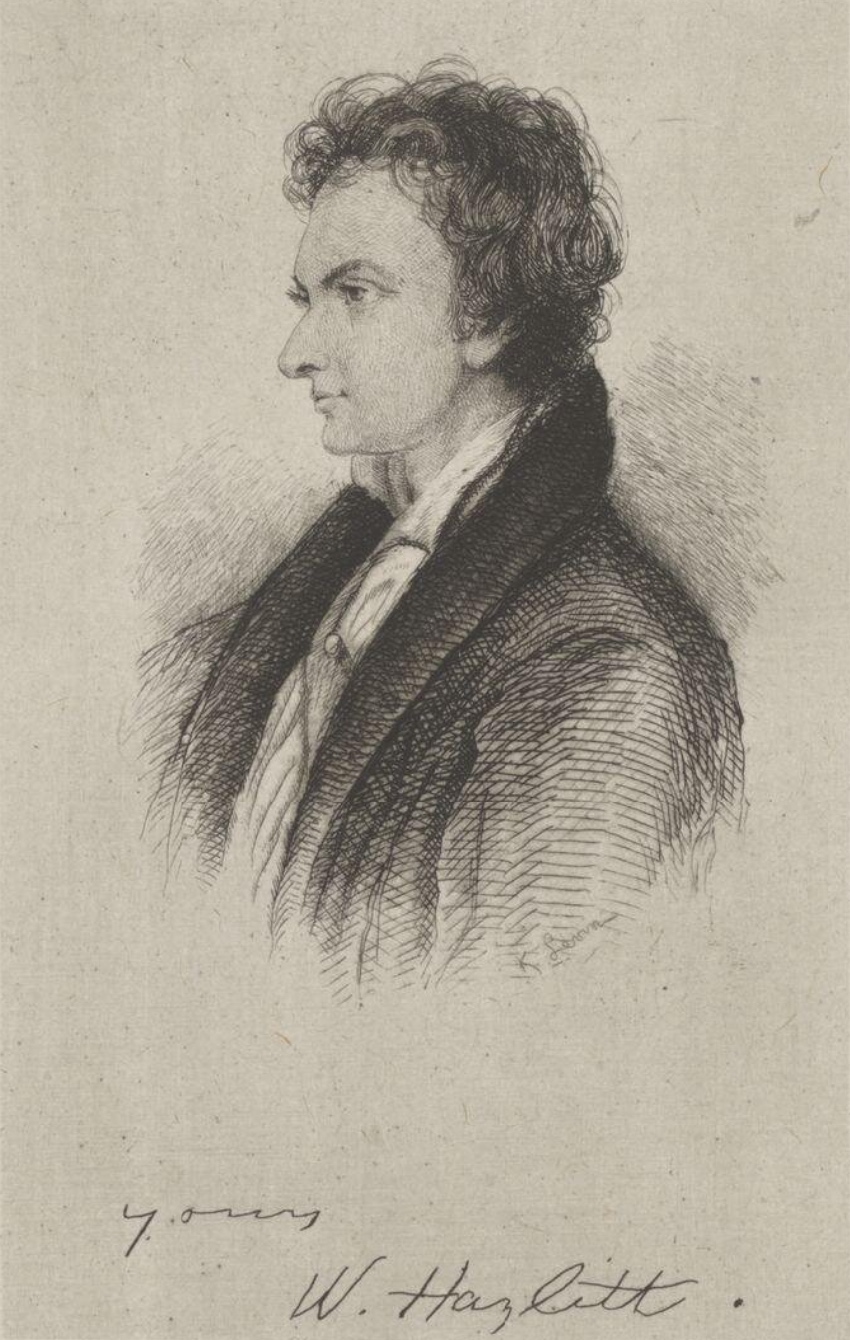

youngHazlitt, Victoria & Albert Museum (F.92-21. H. Beard Collection). Click to enlarge.