May 1819: Poetic Progress Primed & Prepared, & Ode on Melancholy

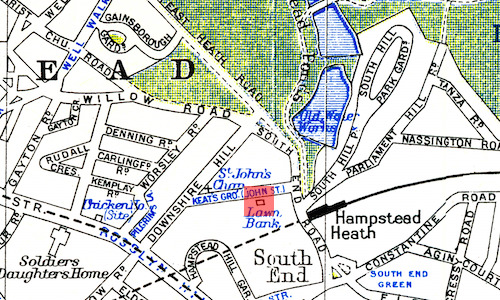

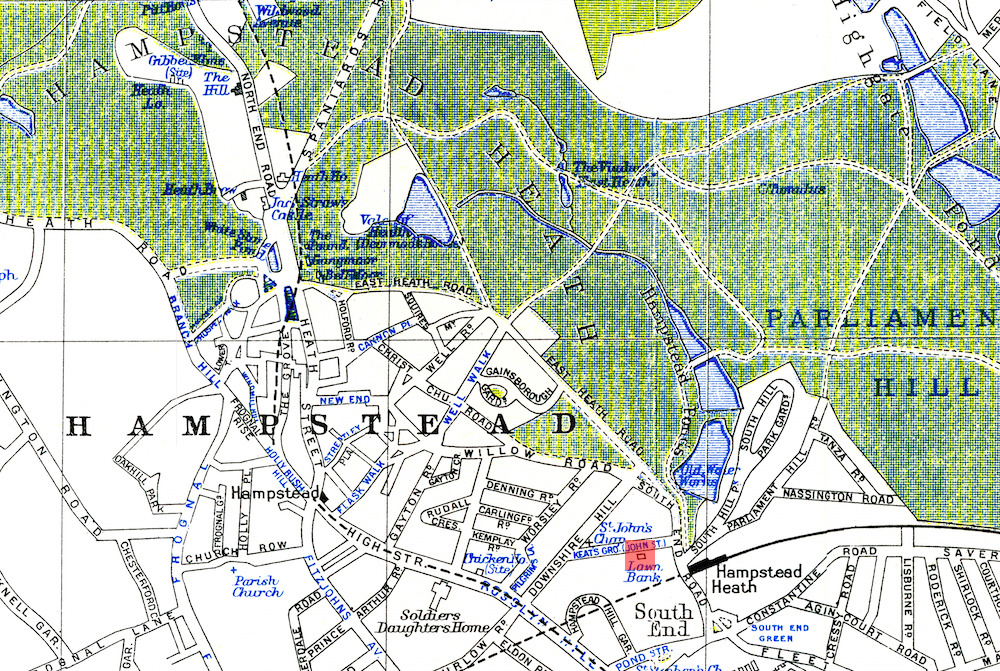

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

When it comes to Keats and poetic achievement, the word crowning

recalls a moment

when, back in March 1817, and in the spirit of poetic sociability, Keats and his mentor

at the

time, Leigh Hunt, embarrassingly (yet playfully)

place laurels on their heads to glorify their suburban poetic prowess. But May 1819

and the

immediate period around it is Keats’s true crowning moment. Keats likely writes at

least

three, and perhaps four, extraordinary odes: on Psyche, a nightingale, a Grecian urn, and melancholy. Yet, in terms of what we know about

the compositional circumstances of these odes and what Keats thought about them, there

is

little to go on. The best commentary on them remains Keats’s own poetics, articulated

in his

letters.

And yet, May 1819 seems otherwise to be a largely uneventful month, following from (what he variously calls) the laziness, languor, indolence, and ennui of early 1819 that, by about mid-April, he breaks out of.

What happens? What entwined factors have lead to Keats’s poetic progress the first months of 1819?

The accumulated effect of much deliberate and continuous study—of Shakespeare, Milton, and Wordsworth in particular, with perhaps Dante’s powers lurking in the background—plays a significant role in what appears to be Keats’s sudden progress at this point; and, over the last few years, accumulative support from his social and intellectual network also hugely contributes to his prodigious advance—beginning very early with Charles Cowden Clarke and then Hunt in October 1816, but led forward and invariably encouraged by friends like Charles Brown, Benjamin Bailey, Charles Wentworth Dilke, Benjamin Robert Haydon, John Hamilton Reynolds, James Rice, Joseph Severn, Richard Woodhouse, William Haslam, and John Taylor. Their unequivocal belief in his poetic gifts is remarkable, especially given that most of these figures were older, better known, or more experienced. Singularly important is another friend who comes a little later into Keats’s circle: critic, essayist, and lecturer William Hazlitt. His ideas about the qualities of Shakespeare’s genius and Wordsworth’s gifts and limitations greatly influence Keats’s thinking, and Hazlitt’s evaluations push Keats to study the work of these writers in an even more deliberately critical way.

Keats also, in 1818, had come to terms with the insufficiencies and imperfections of his long, perambulating poem, Endymion. And, as he expresses just at this time, in a letter of 3 May, he quite amazingly can now articulate what he believes is wrong with existing sonnet forms—that they are constrained and tonally biased; the timing of this insight takes us to the kinds of stanzas he develops for his odes. (Keats expresses these formal issues in an ingenious sonnet, If by dull rhymes.) He has also, within the past month, at last put behind him immature and enthusiastic notions of fame that, in his earlier writing, held him with wayward goals and unproductive poetic impulses (this new thinking is seen in On Fame—Fame, like a wayward girl and On Fame—How fever’d is the man).

At the same moment, and beginning about two years prior, this progress in his poetry is well anticipated in his epistolary poetics before being exhibited in the poetry of spring 1819: again, Keats develops a fairly clear sense of what he needs to address and how to address it, but, until this point—the first part of 1819—he had not yet struck upon poetic forms, mastery of voice, and befitting subjects to register and then express these depths. At this moment, at least, the ode (as Keats innovates upon it by ingenious maneuvering of the sonnet, as mentioned above) both releases and, significantly, positively captures Keats’s lyrical artistry: that is, the lyric impulse toward intensity, indulgence, and subjectivity is formally curbed by the ode’s structured demands to focus upon a subject, whether this takes the form of reasoned self-debate or a finely measured surrender to sensation and imaginative capability.

And then, in his own unsettled life: with the recent death of his beloved younger brother, Tom; with the emigration of his other younger brother to America; with his younger sister’s future seemingly controlled by the trustee of the family estate; and with the uncertainties of his own health, finances, and relationship with Fanny Brawne, Keats finds himself in the spring of 1819 necessarily focused upon framing his life and goals in the larger and more intense complexities of life and art; he finds himself arriving at a profound acceptance of sorrow, suffering, and loss. Interestingly, but not quite paradoxically, such complexities and uncertainties creatively liberate him without much fanfare, as if to say, Now is the time to write, independently, as John Keats.

In short, by May 1819, Keats has developed a determined critical sense of what, poetically, he should and shouldn’t do, and what he should or shouldn’t emulate. He has, for the moment, developed a sense of mastering his own domain.

So first, there is an ode that reflects Keats’s aim for some kind of poetic control of a potentially meandering and murky subject:

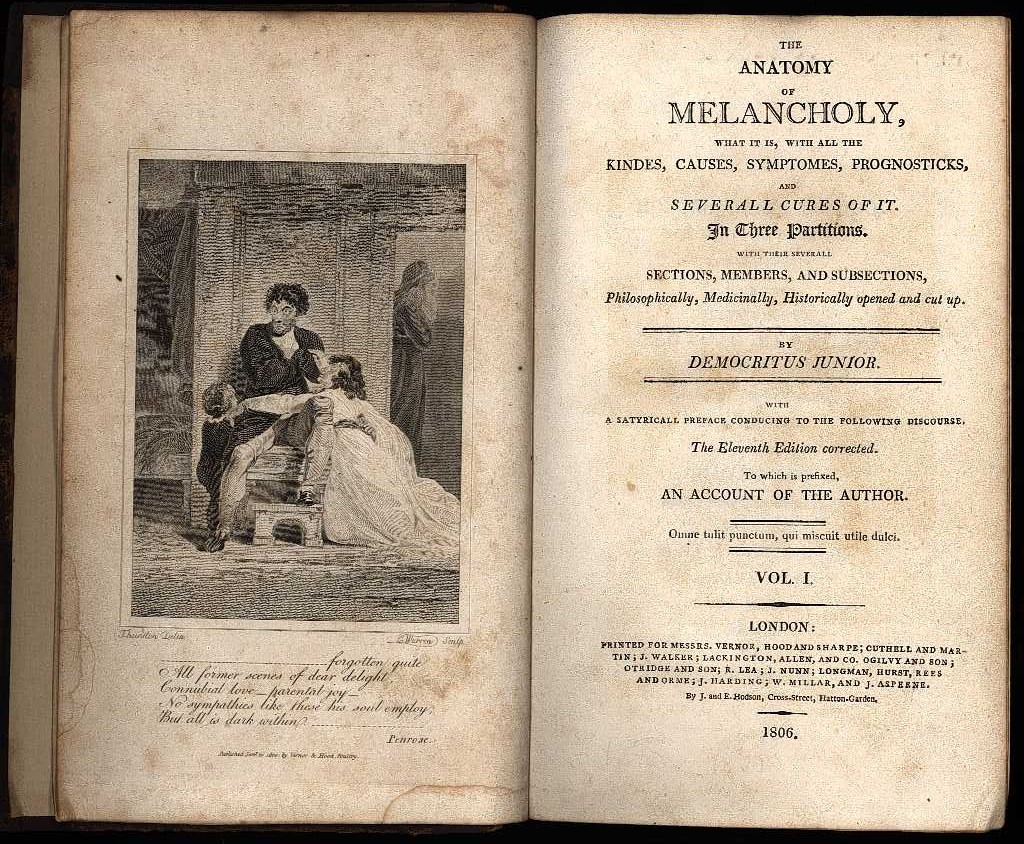

Ode on

Melancholy, like the other odes, reflects Keats’s new condensation of expression

and form, rather than the flowery affectations, random structure, and poetic indulgences

in

almost all of his earlier poetry. As mentioned, the ode’s form forces constrained

exploration

of a particular subject; this, in fact, is probably the most structured of his odes,

which is

not surprising since it openly offers a 3-part argument: warning, advice, conclusion.

One of

the reasons melancholy intrigues Keats is that first, as a state, it is both emotional

and

philosophical; second, as such a state, it necessarily embodies contradictory and

conflicting

emotions; and finally, it has a history (dating from the 16th century) of association

with an

artistic, contemplative temperament. In particular, melancholy (in part as Keats selectively

gleans it from Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy, a copy of which

he owned) embodies the human conditions of joy, sadness, and suffering, as well as

ways to

experience these—through thought, sensation, and a sense of beauty. As such, and even

with its

mysterious and often unannounced falling upon us, it rules us and is to be revered:

Veil’d

Melancholy has her sovran shrine

(25). In a broad sense, the poem is about mutability

and the need to both indulge and accept its contradictory natures. To massage one

of Keats’s

own critical phrases, it is a state of negative capabilities.

Ode on Melancholy

is not as striking or iconic as the urn and nightingale odes,

perhaps because there is no one object—no single trope—to, as it were, imaginatively

focus

upon. That is, it does not easily invoke a single or singular focus. So too does Keats

resort

to some poetic banalities: at one point, in six consecutive lines, we encounter a

weeping

cloud,

a drooping flower, a shrouded hill, a morning rose,

a breaking wave, and

some globed peonies

(12-17). And then, again, that three-stanza structure seems quite

simple: 1. Don’t do this; 2. Do this; 3. What this means. But these all camouflage

the poem’s

unique exploration of our mutable and vulnerable emotional lives, and that to embrace

our

condition fully is to embrace its truthful, though sad, beauty.

This month, Keats will also be mentioned in passing in The

Examiner (23 May, p.333) as a poet who emerges out of the old world of the

imagination,

and therefore marks a challenge to the contemporary scene. Hunt, who is likely the

author of the short piece, is largely unaware of the new poetic directions Keats’s

poetry is about to take

this month.