31 May 1819: Controlled Intensity & Timeless Drama: Ode on a Grecian Urn

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

May 1819 is, as far as we know, not filled with memorable events: Keats visits his

sister,

Fanny, a few times; he sees the usually obdurate

guardian of the family estate, Richard Abbey, over

money and family matters, though Abbey on this occasion is oddly pleasant; on or about

12 May

he finally gets a letter from his brother George

and his wife who emigrated to America mid-1818; he has a period of being confined

due to

illness; and he returns some borrowed books, long overdue. He even briefly entertains

becoming

a ship’s surgeon and moving from Hampstead, though 31 May he writes to Sarah Jeffery

that he

would prefer a feverous life alone with Poetry

and to conquer his anxiety and indolence

by writing some grand Poem

(letters, 31 May). By 9 June, the ship’s surgeon idea seems

pushed aside. The pull of poetry or some kind of literary life is simply too strong.

Though in terms of scale Keats does not write a grand Poem

in May, during the spring

months, he does compose poems that centrally contribute to the reason Keats becomes

a

canonical and hugely influential poet: he writes the majority of his so-called great

odes.

Though their dating is not fully certain, the compositional span for most the

these poems could be a little as about six weeks of April into May. One of these poems

is his

Ode on a Grecian

Urn.

The general idea to write a poem on the urn may have come about after Keats traces

or makes a

drawing of an engraving from the Sosibios Vase. Imagery for the poem may also have

been drawn

from the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum (and perhaps specifically, that heifer lowing

at the skies

[33]). Keats knew the Marbles very well, initially, at least, via his very

good friend (and public defender of the Marbles), the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon. Keats in fact writes about the Marbles

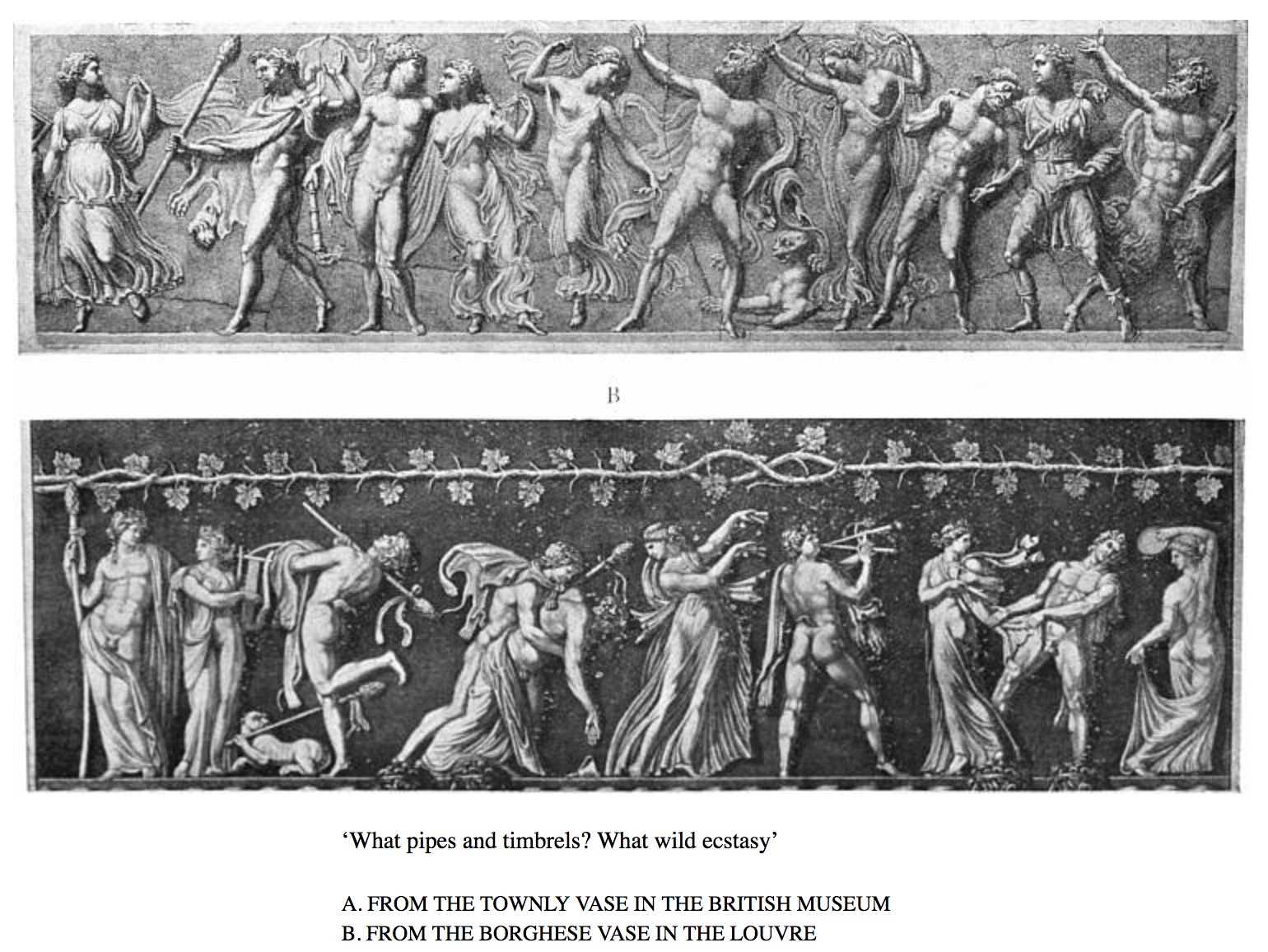

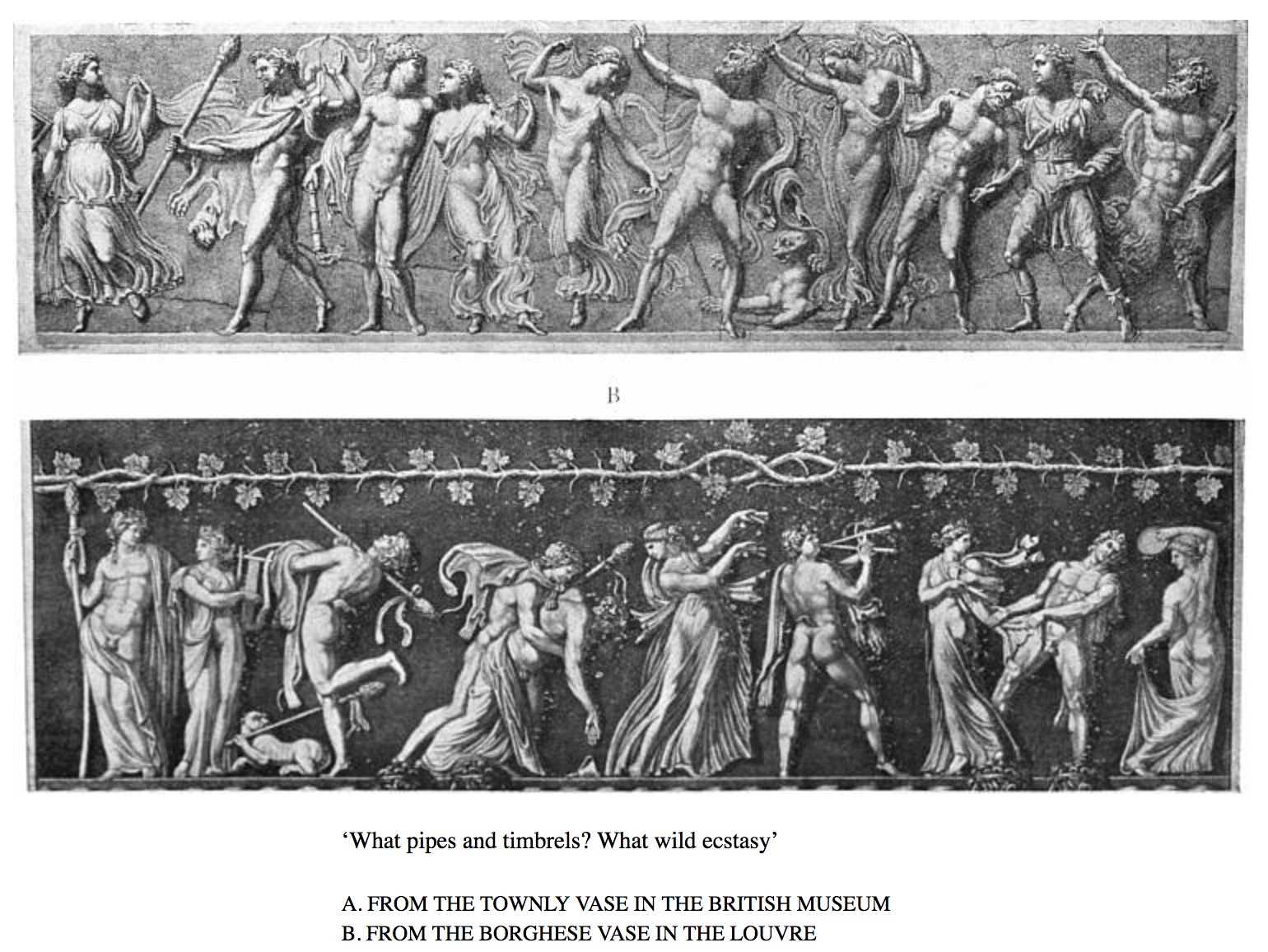

after seeing them in March 1817 with Haydon. So, too, does another vase, the Townley

Vase

(with Bacchus, Pan, and other figures), have possibilities as a source.

Most importantly, though, are Keats’s aesthetic and philosophical interests in classical

art

that, for him, possesses time-defying form and values. Thus, resonating in the background

of

Keats’s progress is the expansive idea that Keats would have known via a number of

places,

from Ovid onwards (and even via a mistranscription of Da Vinci quoting Petrarch),

that the

beauty in life does not perish in art (Cosa bella mortal passa e non d’arte

); human

suffering, aging, and death are the great thieves, but art can preserve the truth

of beauty.

This idea, then, of persistent beauty through art begins to inform his own poetics in ways that begin to translate into his mature poetry of 1819. That is, the mystery of these beautiful, silent forms on the urn he pictures—motionless forms that move timelessly through time—profoundly stirs and then motivates Keats’s poetic goals. He describes some figures that, though quiet and still, are yet primed by desire, but, for eternity, will never give into it; in this way, we could say that Keats does not give in to his own time. This larger thematic and philosophical conversation is one that Keats hopes his poetry will join.

And so, by 1819, Keats is able to both thematically express the meaning of this stirring

as

well as emulate their forms with equally controlled intensity—but represented in language.

How

does he achieve this? Keats now, in his best poetry, packs much into almost every

line: he has

come to be self-conscious of sound and rhythm (what Keats might call melody), while

at the

same time he develops measured intensity that does not lead to stumbling or confusion

or

distraction. He finds in his spring odes an idiom that is both natural to him as well

as to,

he feels, that natural movement of English, particularly at a syntactical level. In

his

earliest poetry, such critical self-consciousness and practice is undeveloped, and

his

descriptions are often disturbed, undermined, or randomized by arbitrary and mannered

phrasing. Keats wants art that defies or at least conceals its own artfulness. Keats

has

already early profitably described this as the poetical character

; now, in 1819, he

can, as it were, live this in his art.

The drama of Ode on a

Grecian Urn is, in a way, simple: the speaker does not know who these figures

on the urn are, where they are, or even exactly what they are doing. But these

disagreeables

matter little—they come to evaporate

by the time we come to the

poem’s exceptional conclusion: all we need to know

is the urn’s larger message, that

Beauty is truth, truth beauty

(49-50). And much of that truth is in the expressive,

mysterious beauty of both the urn and (if Keats gets this right, and he does) the

poem. The

truth, too, is in the sweetening (11-14) strength of the imagination, which, for Keats,

is

rooted in the immeasurable and the eternal: the images Keats foregrounds exist For

ever,

in the evermore,

in the world of cannot,

of never, never,

of

eternity

; they will remain,

unravishable, beyond the weary world of grief and

aging (1, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 24, 26, 27, 38, 45).

The urn, as Keats represents it, purposely defies history, while also (at least for

the

speaker) defying a close, material reading. And that, again, is what great poetry

often does:

it defies history by pulling and teasing us out of our time and our human condition.

However,

the tension in the poem is an awareness of our passing, while the urn, shalt remain [. . .]

a friend to man

(46-48) for all time. The wonderful—and Keatsian—paradox in the poem is

that the unknowable urn is nevertheless an object of consolation. Again, it is negatively

capable.

So, too, does the poem enact another idea central to Keats’s poetics: the urn is created

by a

particular human hand and imagination, yet nothing about the artist is known or addressed:

we

have only the creation, the object—the urn itself—into which the creator (whoever

made the

urn) has been absorbed; the sculptor has, as it were, fallen into and is unseeable

within the

created object. This is the camelion poetic Character

to which Keats aspired—who,

without an identity, fills the body of the urn and the figures and forms upon it (letters,

27

Oct 1818).

Keats’s progress: he finds subjects and forms in which he can now enact his poetics, using either an involved, emotional speaker or a more deliberately controlled voice. In a way, Keats’s poem does to us what the urn does to the poem’s speaker.

The poem thus takes themes that inevitably attract Keats: the difference and tension

between

unchangeable art and mutable humanity; the experience of human suffering through the

experience of sympathetic imaginative capabilities. For Keats, though, what remains

in focus

is the Wordsworthian notion that we all necessarily carry the burden of what it is

to be

human, looking for that which binds, restores, and sustains us in the midst of sorrow

and

loss—that one human heart. Wordsworth almost

exclusively uses nature as the trope to foreground this, his great theme; Keats, here,

uses

art. This connection between Keats and Wordsworth is anticipated in a key moment of

Keats’s

poetics when he declares that Wordsworth’s depth and genius is in exploring what Keats

calls

the dark passages

of human life (letters, 3 May 1818). Keats’s best work can, in this

light, be seen as making similar explorations. We could say that, at last, Keats too

is

entering those chambers of life’s large mansion of many apartments

that he believes

Wordsworth entered—a place beyond the balance of good and evil

(3 May 1818).

Finally, as in Ode to a

Nightingale, the speaker borders on emotional excess in expressing his desire

to know what he cannot know—in this case, the meaning of what the urn literally portrays.

The

internal rhetorical rhythms in the poem—those moving between questioning, conjecturing,

and

settled understanding—are finely balanced, and the poem’s unity in part comes from

the drama

of speaker’s conclusion that the truth of the urn’s silent beauty will forever be

a

friend

to mankind, despite the distress or sorrow of human experience. And this is

what Keats hopes his poetry will likewise achieve.

To place the poem in terms of Keats’s poetic development: Although Keats manages to

compose a

significant and atmospheric romance toward the end of January 1819 (The Eve of St Agnes), as mentioned,

it is not until about the second half of April 1819 does a fully productive poetic

temper seem

to return, and it returns with remarkable advances in his poetry. This progress is

first

marked by a short incursion into the ballad form with La Belle Dame sans Merci, a

highly allusive poem that can be read as both an allegory and an application of his

poetics.

It gets much of its understated and stark force by enacting Keats’s idea of Negative

Capability

(21/27 Dec 1817): the poem leaves us and its protagonist—the

knight—upon the cold hill’s side

(44), out of time, stationed somewhere between

mystery, uncertainty, and doubt. The only truth is the irresistible, fragile, yet

dangerous

Belle Dame, who, in the end, exists somewhere between warm, sensuous love and cold,

woeful

reality: she is evocative, seductive, Full beautiful

(14), and, given that she speaks

in a language strange

(27), is unknowable; yet she loves and is loved. She is an ideal

that takes the knight out of the real, only to return him, Alone and palely loitering

(46). This is Keats’s warning about the darker yet beautiful power of art (poetry,

music,

sculpture), and this also sounds in his other poem, just written, Ode to a Nightingale. The

phrase—Alone and palely loitering

—in a good example of Keats’s new ability to both

condense the imagery and to self-consciously and internally form it with subtle sound

and

rhythm: the fine excess of the L-sound beautifully escorts us through the phrase,

with the

most telling image in the poem.

These too, then, are the properties of and the power in the kind of poetry to which

Keats

aspires and now, at last, achieves. As Keats also writes in his letter that describes

Negative Capability,

excellent Art

in its intensity is capable

of making all disagreeables evaporate from their being in close relationship with

Beauty

& Truth

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817), and this is how the poem positions our response.

Now, rather than in a pared-down ballad, Keats in a highly controlled and elaborate,

experimental ode (that builds upon a massaged sonnet forms) sets his speaker (and

us) before

the beauty of a classical urn, yet these same characteristics and poetics are set

into the

poem.

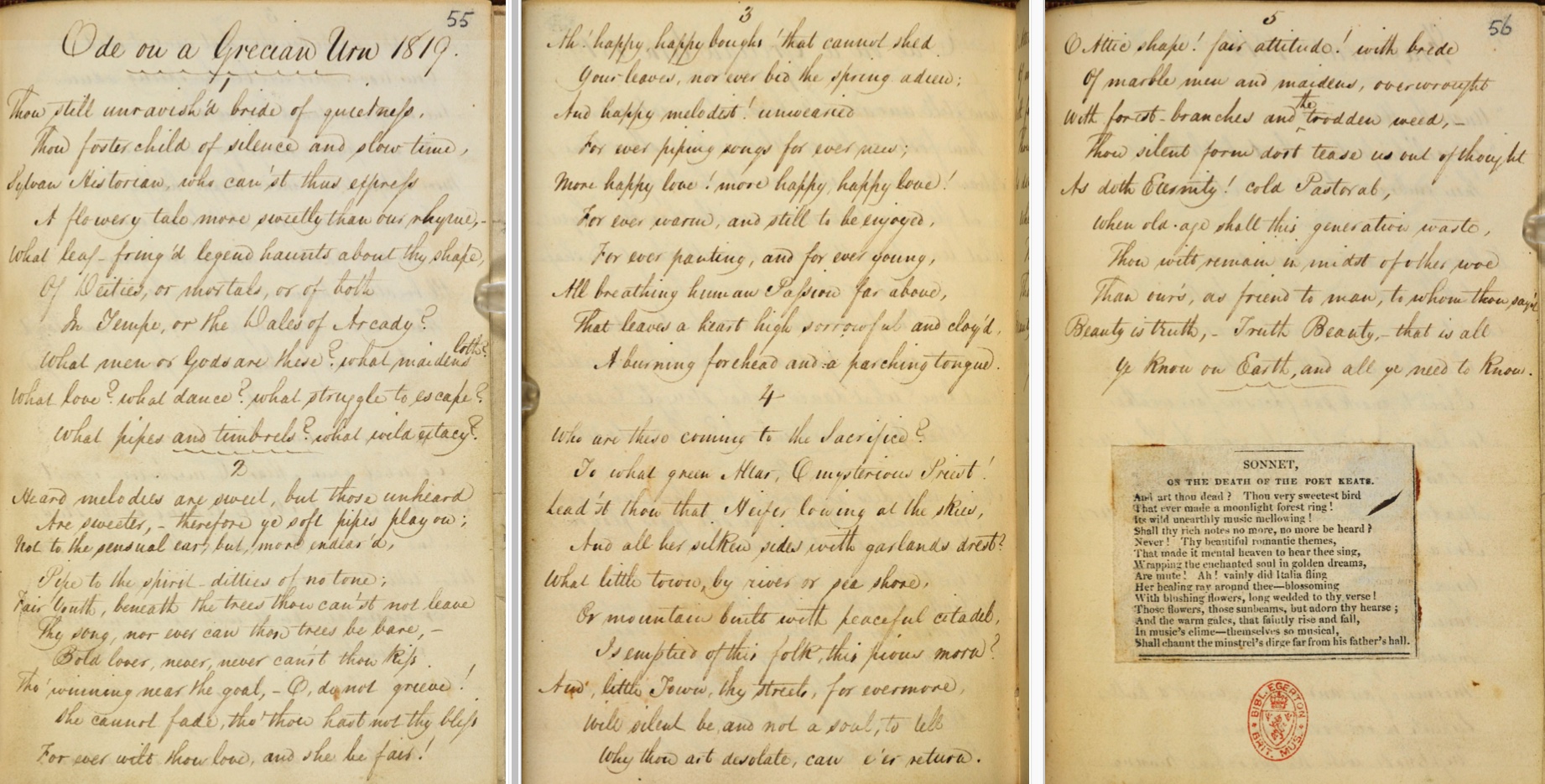

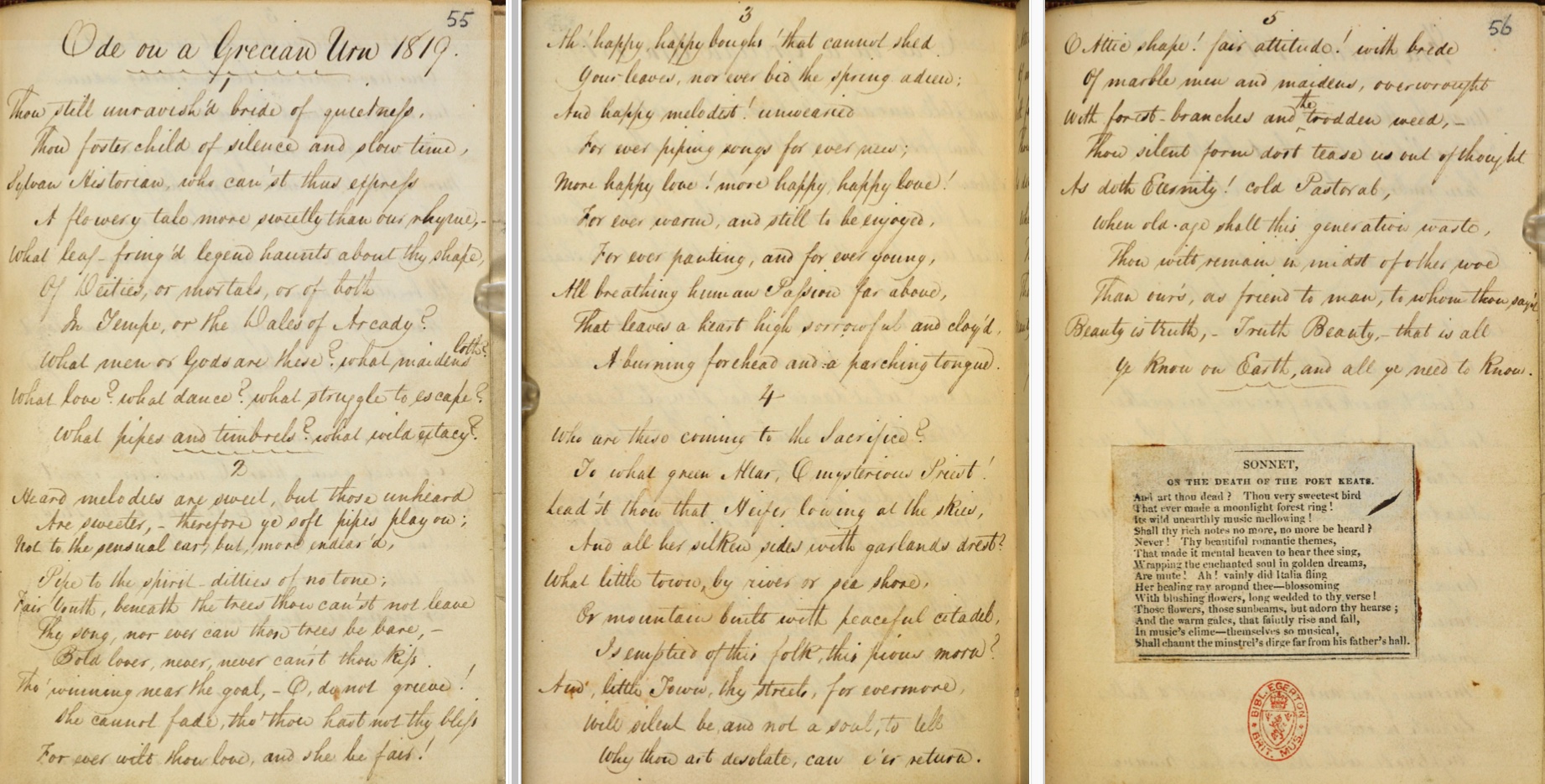

Ode on a Grecian Urn is first published in Annals of the Fine Arts, January 1820 (pages 638-39),and is subsequently published as the fifth item in Keats’s third and final 1820 collection, following Ode to a Nightingale and preceding Ode to Psyche.

Ode on a Grecian Urnin the hand of Keats’s brother, George (British Library, Egerton MS 2780). Click to enlarge.