20/21 September 1818: Haunted by Tom, Plunging into Abstractions

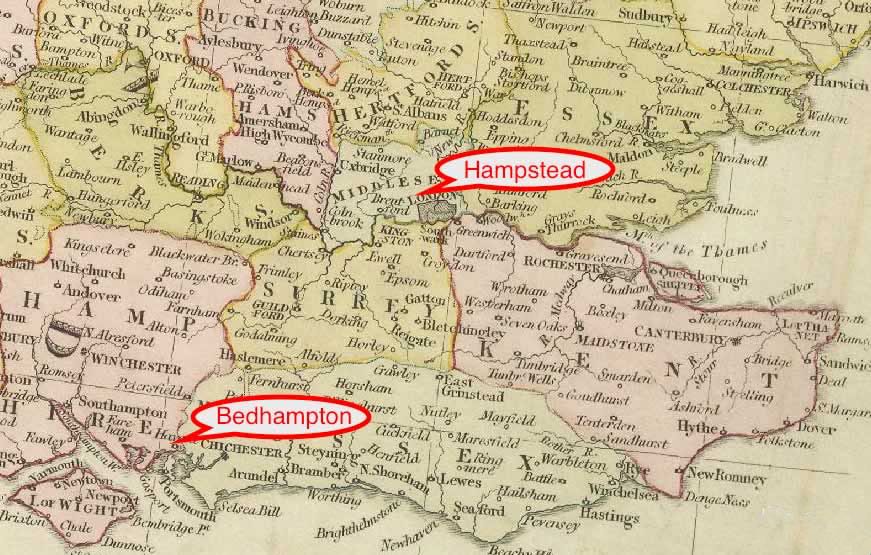

Bedhampton, Hampshire

From Hampstead, Keats, aged 22, writes to his friend, Charles Wentworth Dilke, in Bedhampton. Dilke is a decently-connected reviewer, critic, journal editor, and scholar, though he held the apparently soft position of a Navy pay officer until 1836. Along with one of Keats’s other close friends, Charles Brown, Dilke is co-owner of Wentworth Place, a double-house in Hampstead built 1814-1816 (in 1925 it becomes a museum—Keats House). With Brown’s kind invitation, Keats will move into Wentworth Place in early December 1818, almost immediately after the death of his younger brother, Tom. Beginning mid-August when Keats returns exhausted from his curtailed walking excursion with Brown, much of his attention is taken with caring for Tom, who agonizingly fades toward death from consumption. Consumption offers anything but a kind death.

Keats writes to Dilke that Tom’s condition presses heavily upon him. It compromises his

energies and complicates his emotions—he says he is in a funk

and feeling

nervous

on 22 September, though this state is sometimes part of Keats’s own emotional

pattern. Keats is himself also unwell enough to be given medical advice to avoid damp

nights.

Although Keats wants to purposefully study poetry for the sake of his own poetic growth,

he

instead, and with some guilt, now feels obliged to write and plunge into abstract images to

ease myself of his [Tom’s] countenance, his voice and feebleness.

At this very moment he

writes something similar to another good friend, John

Hamilton Reynolds, about the conquering and feverous relief of Poetry

: it

allows him to escape from the state of Poor Tom

into abstractions which are my only

life

(22 Sept).

And so Keats’s poetic progress is, for the moment, directed to what he should or can

do in

the face of Tom’s suffering. He feels it is

something of an emotional or ethical crime to even think about the fame of poetry

at

this time, but he does, which tells us something about Keats’s honesty, ambitions,

and complex

situation. He writes that he does not have enough self possession and magnanimity

to

think otherwise (21 Sept, to Dilke). Keats also

theorizes that some of his anxiety may have come from recently taking mercury, perhaps

to

treat his chronic sore throat, or (to speculate) perhaps to treat lingering effects

of

venereal disease. We have to keep in mind that, in Keats’s time, mercury was given

for an

impossibly wide range of illnesses and symptoms, ranging from dysentery to rheumatism.

Thus writing poetry—or at least a certain kind of poetry—is a guilt-ridden relief

from

dealing with Tom’s condition. Yet diving into

abstractions

takes him into some profitable poetic moments—especially as he begins to

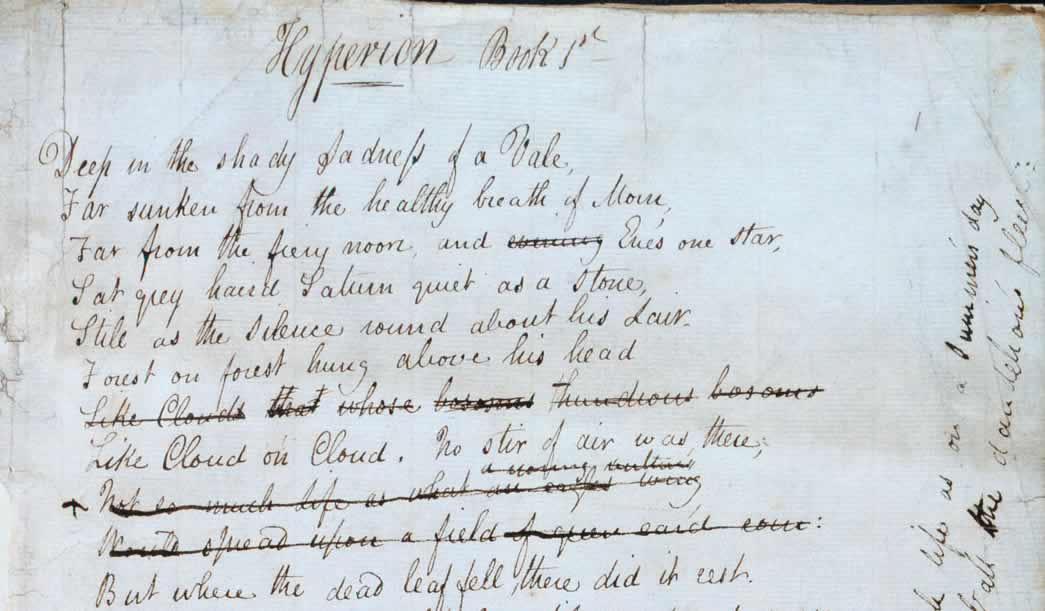

write his Miltonically-styled epic, Hyperion. The poem, though

eventually abandoned after a second effort at completion in 1819, announces a significant

degree of maturity in Keats’s poetic progress, recognizable in the poem’s assured

and

uncluttered opening:

Deep in the shady sadness of a vale

Far sunken from the healthy breath of morn,

Far from the fiery noon, and eve’s one star,

Sat gray-hair’d Saturn, quiet as a stone,

Still as the silence round about his lair;

Forest on forest hung about his head

Like cloud on cloud. No stir of air was there,

Not so much life as on a summer’s day

Robs not one light seed from the feather’d grass,

But where the dead leaf fell, there did it rest.

Click to see a facsimile version

Much of what we have of Hyperion (about 900 lines) strikes a balance of control and intensity, of clarity and concentration, that he aspires to and describes in various letters as essential to great poetry; as usual, Keats’s poetics precedes his poetry. Keats perhaps overreaches with the poem—the poem’s plot bogs down in some uncertainties (perhaps he intended it as an allegory of self-discovery)—but it doubtlessly stirs his ambitions, signals some confidence, and acts as a precursor for what is to come: with his earlier Endymion (published earlier in 1818) he thinks, I can do better—yet the poetry is not really me; with Hyperion, I am doing better—yet the poetry is still not really me. He will soon learn that addressing human suffering and mortality in the face of these abstractions will in fact be part of the material and thinking that leads him to compose his greatest poetry over the next year.

The leap in progress from Endymion (begun April 1817, and finally done with a year later), is, with Hyperion: A Fragment, glaringly obvious: there are far fewer passages and phrases that jump out, as if to say (borrowing from Keats’s own condemnation of poetry he hates, 3 Feb 1818), Look, this is poetry! Admire me! But he still occasionally gets caught up in description governed by analogy, which, poetically, can be hit or miss. He also comes to worry that Milton’s language and syntax is not something he wants to emulate, being at times overly artful (letters, 24 Sept 1819). One of Keats’s poetic axioms is that poetry must both come naturally, and must appear natural. Clearly, much of Endymion did not come naturally, nor does it feel natural (Keats says so himself more than once), but with Hyperion we encounter a deeper, more sustained and unobtrusive voice, though, as mentioned, still not quite his own. But he’s getting there. For Keats, the wonder and power of Milton has to be understood, accommodated, and then massaged before he can move out of Milton’s shadow.

Besides Tom and poetry, Keats lists that

woman

as the third item that takes his attention (22 Sept, to Reynolds). He is likely referring to Jane Cox, whose voice and shape [. . .] has haunted me these two

days.

Thinking about her has kept him awake at night. Nothing comes of it.

September is also framed by two nasty attacks on Keats and his poetry, one in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, published at the beginning of September, and the other in The Quarterly Review, which appears at the end of the month. Both pillory Keats’s lax and unmanly poetic style, but they are also determined to sink Keats by nominating him as the unfortunate apprentice of Leigh Hunt, who was indeed Keats’s mentor in the early phase of his poetic development, roughly the latter half of 1816 and for a little less than a year. Despite Hunt’s crucial role in introducing Keats’s poetry to a significant faction of London’s literary world by publishing Keats, and, more crucially, by introducing Keats into a network of writers, poets, editors, and publishers, moving beyond the sway of Hunt and Hunt’s poetry is something that Keats is vitally aware of; the Hyperion work is evidence of such movement. In fact, excising poetic connection with Hunt is crucial, though Hunt remains a strong supporter, and Keats has a side of him that accommodates Hunt’s support. This will become clear later, when Keats himself becomes ill, and Hunt generously and without question takes him in (see 23 June 1820 for more on this moment in Keats’s life).