14 September 1818: An All-Nighter with Friends & the Drivelling Idiocy of Endymion

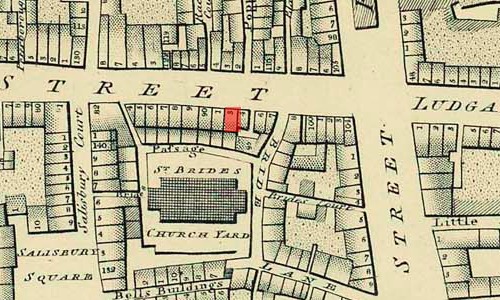

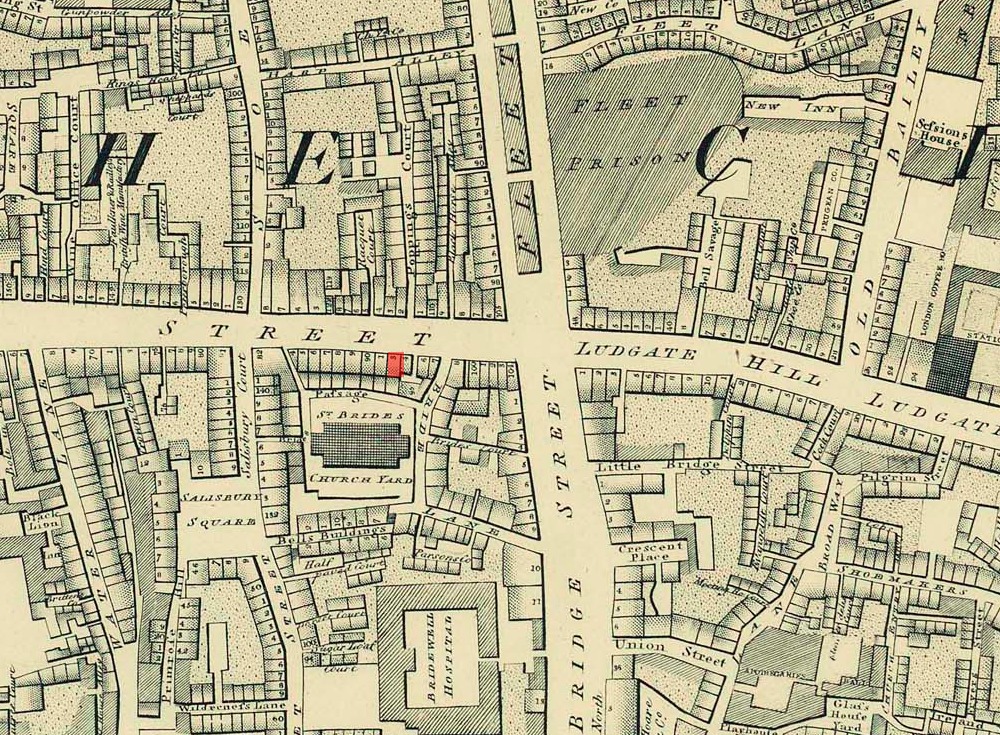

93 Fleet Street, London

The address of publishers [John] Taylor & [James] Hessey, who publish Keats’s Endymion in 1818, and will publish the 1820 volume. Where, on the 14th, Keats has an all-nighter with Hessey, Richard Woodhouse (friend and incredible supporter of Keats), William Hazlitt (friend, lecturer, literary and political critic, essayist, and so-so painter), John Percival (from Wadham College, Oxford), and a few others.

Around this time, Keats (aged 22) becomes aware that Hazlitt has sued Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine

for libel. The suit is dropped; Blackwood’s settles

out-of-court. The suit’s history: Blackwood’s has called

Hazlitt an impudent charlatan,

a mere quack,

a paltry creature,

and he is

accused of various hypocritical behaviors (the culminating attack in Blackwood’s is called Hazlitt

Cross-Examined). In truth, there were some aspects of Hazlitt’s personal history that

well deserved a raised eyebrow. Hazlitt seemed to have three characteristics that

made him a

target of abuse: his obvious smarts (paired with his gift for assertive prose to express

those

smarts); clear republican sympathies (today he’d be one of those darn radical lefties);

and

his inability not to speak out on anything that set him off—and many things did (this

inability gets translated as gross egotism). He had a pretty good temper.

Keats gets much from Hazlitt—ideas about other writers and aesthetics, in particular.

Hazlitt’s larger idea is that the imagination is a

representational faculty that works through feeling and thought. That it is a faculty

that

shapes and connects, even as it is revelatory and penetrating, resonates with Keats

as he

works on a poetics that will govern and propel his poetry. So too does Hazlitt’s belief

that

true poetry is the pinnacle of the imagination’s application, that, even though it

is never

fixed,

it has the power both to raise our own being and to animate the universe.

Poetry, in short, represents the highest form of our desire to feel and to know. When,

in his

1818 essay On Poetry in General (Hazlitt’s most high-minded

definition of poetry, based on his lecture of early 1818), Hazlitt, in writing that

poetry

is the most vivid form of expression that can be given to our conception of anything,

whether pleasurable or painful, mean or dignified, delightful or distressing,

anticipates what Keats writes to Woodhouse 27

October 1818: he passionately embraces the character of the camelion poet,

one that

enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it foul or fair, high or low, rich or

poor,

mean or elevated [ . . . ] It does no harm from its relish of the dark side of things,

any

more than from its taste for the bright one.

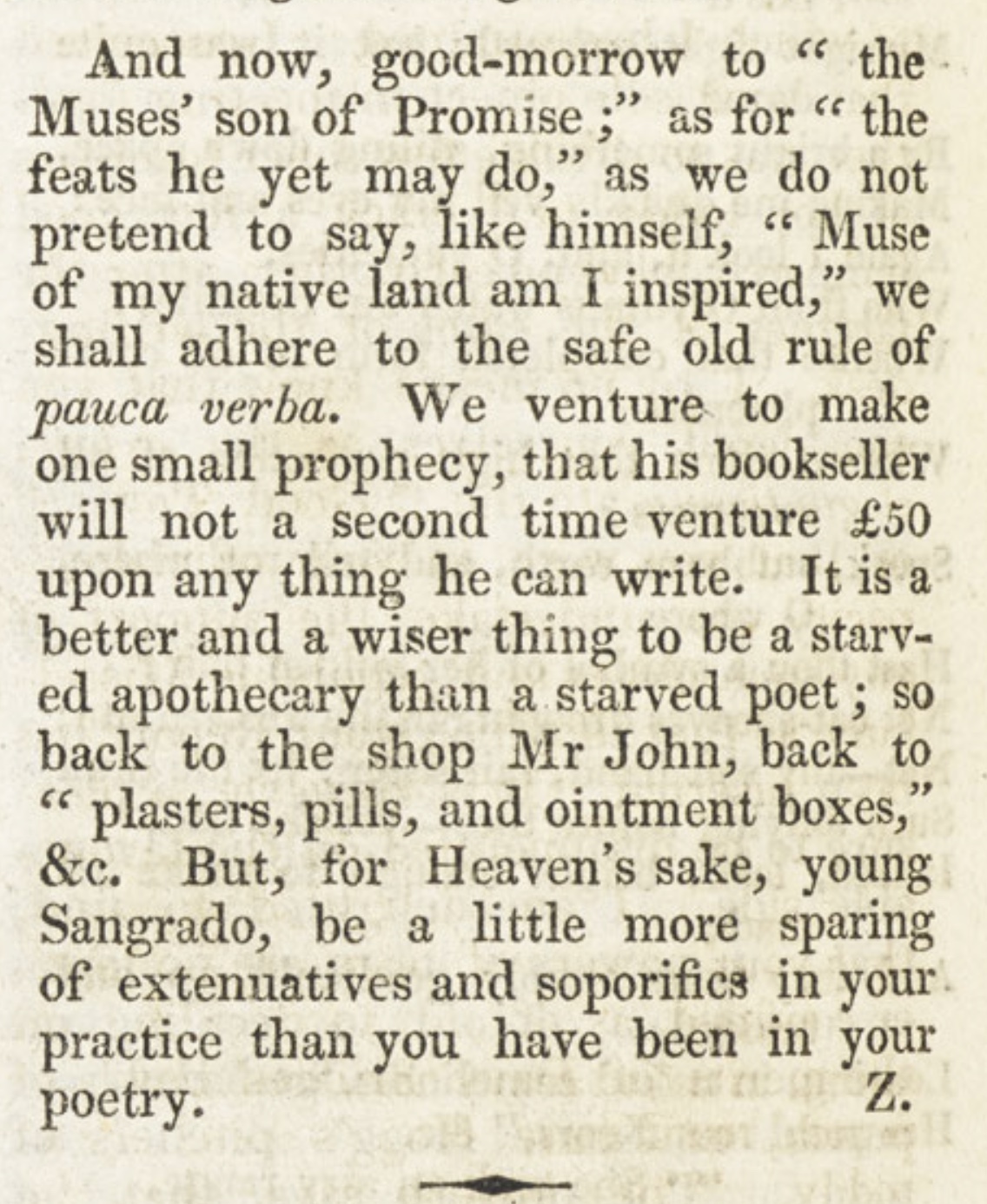

This August 1818 issue of Blackwood’s that slams Hazlitt

also happens to be the very one in which Keats’s poetry, and particularly Endymion, is attacked

with some condescending eloquence: The phrenzy of the [1817] Poems was bad enough in its way, but it did not alarm us half so seriously as the

calm, settled, imperturbable drivelling idiocy of Endymion

(p. 519). The reviewer, who calls himself Z

(we know it to be

John Gibson Lockhart), views Keats as a mere

callow and unfortunate follower of Leigh Hunt,

Keats’s friend and early mentor—and the first to publish Keats. Openly coloured by

partisan

politics and utter disdain for Hunt’s style, values, and personality, Keats—a mere

boy

—is viewed by Z as being infected by the incurable disease of wanting to write

poetry as Hunt’s vulgar prototype.

When applied to early Keats—that is, to Keats’s published work up until Endymion—there is a fair amount of truth to Z’s charges—much of the poetry is not that good; and, in the case of Endymion, it is wandering, stretched, overly pleasured by poeticisms, and too often driven by rhyme rather than reason. But by 1818—beginning about mid-1817—Keats is greatly aware that association with Hunt (with both his politics and style of poetry) is unfortunate and somewhat maddening; however, after initial enthusiasms, it might also have stirred him to develop a stronger, independent poetic character.

In fact, during the last part of September 1818, Keats self-consciously assesses his poetic independence and originality—especially relative to the greater accomplishments of Milton, Dante, Wordsworth, and Shakespeare. Although he worries that there is no longer anything original to be written, he likely begins work on the ambitious Hyperion, attempting, it seems, to emulate aspects of Milton’s form and voice in order to write poetry of significantly heavier import than the mainly poeticized meanderings of Endymion. He will, however, come to realize that Milton’s style is not his own, though in attempting to capture Milton’s elevated tone, he raises his own. That is, in critically confronting Milton’s style and accomplishment, Keats is determined to formulate his own.

At this time, another ridiculing and nasty review of Endymion comes Keats’s way. Predictably, Keats is once more accused of echoing Hunt’s lightweight, affected verses (John Wilson Croker, Quarterly Review, April 1818). While at first the hostile criticism seems to have hurt Keats, his resolve is, in the end, more striking: failure and criticism will push him forward.

As mentioned, being seen as constantly under the wing of Hunt must not have sat well with Keats, and is no doubt a shadow motivator for his own self-determined progress. But first, he has to deal with not only his brother’s (Tom’s) waning health, but also his own, and in particular a worsening throat.