24-25 March 1818: Nettles, Isabella, & Hunt’s Affectatious Title

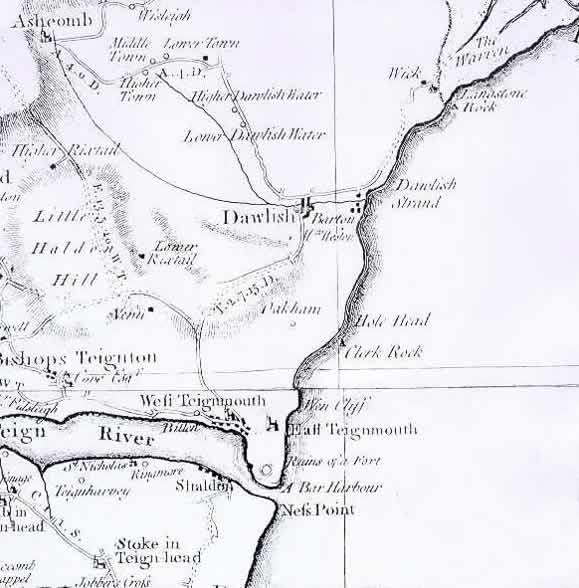

Teignmouth, Devon

Keats writes to his good friend, the sensible and witty James Rice. Keats has been in Teignmouth for over two weeks; he stays for about two months. He joins his younger brother, Tom, who has clear signs of consumption. Keats’s hope is to put the final touches (corrections and a preface) on Endymion, the long poem on which he has been working fairly steadily for almost a year.

In the letter to Rice, Keats expresses, a little

playfully, a life-theme—a theory of Nettles.

He posits that how happy

one’s

thoughts might be if they could remain settled and content, with feelings quiet and

pleasant.

But, he notes, Alas! This never can be.

Mutability, complexity, and

darker, uncertain elements cannot be kept in check by any philosophy. At his most

penetrating

moments in his poetry-to-come, these elements will combine in an acceptance of uncertainty

and

sorrow through a capable imagination, one that equally embraces despondency and hope,

joy and

sorrow.

After waggishly wondering if, in a world of non-varying atoms, the smart matter of

Milton’s head might find some room in someone else’s

empty head, he expresses hope for the health of his ill friend, John Hamilton Reynolds, and he notes Tom’s health, as well: Oh! for a day and all well!

And

then, to perhaps raise spirits, Keats ends with a lusty doggerel based on visiting

a fair at

the town of Dawlish, Over the hill and over the

dale.

The next day, 25 March, Keats writes an offhand epistolary poem to Reynolds—Dear Reynolds, as last night I lay in

bed. The poem rambles forward by describing some recent disjointed dreams and

what such things might mean. By the poem’s end, he is unsettled about the tooth and

claw of

nature and the troubling moods of one’s mind

(100-6). But most interestingly, in

between these, he accepts that reason and ethics can never be settled

or

knowable—they will tease us out of thought

(77); our happiness is sadly flawed

because we see beyond our bourne— / It forces us in summer skies to mourn: / It spoils the

singing of the nightingale.

These lines, if only in passing, anticipate the region of

thought and source of great poetry that Keats comes to explore in his best work; they

especially anticipate his 1819 odes on the urn and the nightingale, where the human

condition

and time’s powers encounter each other through an unfaltering imagination. Even the

style of

these lines, in their simple, uncluttered, calm elegance, anticipate a voice that

Keats will,

for example, summon in his remarkable ode To Autumn, written in the fall of 1819.

The letter to Reynolds also has a brief,

disconnected but charged comment about his friend and former mentor, Leigh Hunt, who, back in October 1816, more or less launches Keats’s

poetic career while introducing him into a network of writers, poets, publishers,

critics, and

artists. Keats writes, What affectation in Hunt’s title—‘Foliage’!

The reference is to a collection of Hunt’s poetry. That Keats points

to Hunt’s poetic pretensions is yet another sign of his desire to move away from Hunt’s

influence and particular poetic style. Keats seems to feel some contempt for Hunt’s

mannered

poetic posturing. Keats, we know, has for one of his Axioms

that poetry must come

naturally (rather than display artificiality) or better not come at all

(27 Feb). Keats

clearly trusts Reynolds to keep these comments private, since Reynold knows Hunt very

well,

and Keats is still in contact with Hunt, having met and dined with him at least a

couple of

times the previous month. Worth keeping in mind is that only a year-and-a-half earlier

that

Keats is a great fan of Hunt as a poet. His comment mocking Hunt’s title is a measure

of how

far—and in what direction—Keats has come.

Among shorter and largely inconsequential poetry, Keats finishes Isabella. Based on Boccaccio’s tale and likely set off by William Hazlitt’s 3 February 1818 lecture, Keats

begins it in February and completes it by 27 April. The poem’s awkward combination

of

sentimentality, mild lewdness, and idealization is in some ways a sideways step in

Keats’s

poetic progress, inasmuch as its ostensible lack of purpose recalls earlier work.

Keats thus

later considers the poem mawkish

(19 Sept 1819), weak, simple, and exhibiting too much

inexperience—and altogether too smokeable

(22 Sept 1819), meaning that he considered

the poem easily open to mockery. He did not want it published, but it ends up in his

1820

volume. (Keats also calls his long poem Endymion mawkish

in its style and

ambition.)

Four things are notable in this period at Teignmouth: first, Keats finally able to

put Endymion and its shortcomings behind him; second, clear signs that

he wants to move forward through application, study, and thought

(24 April); third, a

deliberate wrestling with the poetic dimensions of Milton and Wordsworth relative to

his own poetic character and goals; and fourth, and as an extension of this, further

work

toward a composed stance that will, in his poetry, allow him to reflect deeper regions

of

wisdom, knowledge, and feeling—that Burden of the Mystery

he refers to twice (on 3 May)

in drawing upon Wordsworth’s phrase from Tintern Abbey (38).